|

|

| From

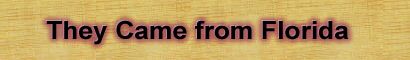

the left: John Jumper, Abraham, Billy Bowlegs Institute of Texan Cultures, Excerpt 72-173 |

The saga of Miss Charles’s ancestors begins in the early 1800s in the swamplands of Florida, where runaway black slaves took shelter with the Seminole Indians, a confederation of culturally diverse peoples through intermarriage and tribal adoption. Although of different ethnic origins, both groups shared a fierce desire for independence and the common goal of resisting European intrusions into their homeland (Mulroy 1993:7). Many of the Florida blacks also carried a heritage of mixed blood. In the history of the African diaspora in the Americas, they are often called maroons, because, after fleeing slavery, they developed their own distinct culture and sense of identity rooted in African traditions. But, at the same time, they also adopted an Indian way of life, wearing bright-colored clothing, turbans, and moccasins (Thybony 1991:92).

They spoke Gullah (Goulah), a variety of English composed of African, Spanish, and Muskhogean Indian expressions also known as Afro-Seminole (Hancock 1980). Gullah has many survivals from African languages spoken by slaves brought to the southeastern United States in the 18th and 19th centuries.

|

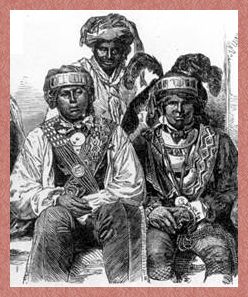

| Ben

Bruno (Bruner), maroon in Florida who served as Billy Bowlegs’s interpreter and counselor Institute of Texan Cultures, 73-1284 |

A constant theme in the recollections of black Seminoles recorded by Porter in the 1940s and in the “rememberings” of modern-day descendants is the fear of slave hunters. This haunting fear must have affected their sense of spirituality and community, for even Creek slave hunters would raid black Seminole communities, putting the families constantly on guard and making them live in uncertainty (Littlefield 1979:179-180). Women were frequently the victims of slave hunters and kidnappers, especially single women and widows with no one to protect them during these chaotic times. One woman and her children were purchased by her husband, a freed black man, but the ownership papers were stolen, and the family members were sold by a Creek. Certainly, however, not all Creek Indians participated in this practice. The Creeks, like the Seminoles, consisted of an amalgamation of other Indian groups, with changing geographical locations and political objectives through time (Mock 2000).

By

1783 Florida was again under Spanish control, and the Seminole maroons

emerged as a distinct cultural and ethnic entity with shared values and

traditions. Maroons joined the Seminole Confederation in 1812; this mutually

beneficent military alliance continued throughout subsequent Anglo-American

wars. During these frequent border skirmishes and the First Seminole War,

the maroons enhanced their fighting skills and learned the evasive tactics

of guerilla-like warfare in the Florida swamplands. Knowledge of white

ways and language also made the maroons extremely valuable as interpreters

and negotiators (Mulroy 1993:17-19).

By

1783 Florida was again under Spanish control, and the Seminole maroons

emerged as a distinct cultural and ethnic entity with shared values and

traditions. Maroons joined the Seminole Confederation in 1812; this mutually

beneficent military alliance continued throughout subsequent Anglo-American

wars. During these frequent border skirmishes and the First Seminole War,

the maroons enhanced their fighting skills and learned the evasive tactics

of guerilla-like warfare in the Florida swamplands. Knowledge of white

ways and language also made the maroons extremely valuable as interpreters

and negotiators (Mulroy 1993:17-19).

Fierce resistance of the Seminoles and Seminole maroons to forced relocation by the U.S. Government led to the Second Seminole War of 1835-1842. Some officials and slaveowning landowners believed that the maroons, rather than the Seminoles, were fanning the flames of war (Mulroy 1993:29). Following the Indian Wars, the Seminole Indians and maroons were to be relocated to southern Florida; however, complaints from fearful landowners, aware of their warlike reputation, prompted the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830.

|

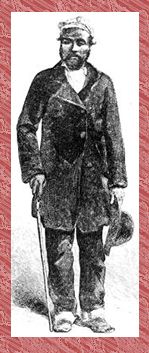

| Seminole Chief

Wild Cat Drawn by N. Orr Institute of Texan Cultures, 72-50 |

Prominent among Seminole Indian leaders was Chief Wild Cat, or Coacoochee. He was the son of King Philip (Emathla), chief of a band of Mikasukis who lived in Florida on the St. John’s River (Porter 1951:1; Swanson 1985b:1-5). Wild Cat was a flamboyant personality, prone to extravagant dress, and revered as a great warrior among the Seminoles.

John Horse, known as Gopher John or John Caballo (probably Juan Caballo) in Texas and Mexico, was the black Seminole chief, a freedman of African, Indian, and Spanish ancestry who also served as Wild Cat’s interpreter. One observer describes John Horse with his plumed turban and “unerring rifle” as a tall, erect, powerful form, with handsome features and “carefully combed long, crinkly hair wearing tasteful Indian garb.” (Porter 1943:10-15)

|

| Black

Seminole Chief John Horse Drawn by N. Orr Institute of Texan Cultures, 72-51 |

His name, Gopher John, was the legacy of a trick he played on an army officer who fancied “gophers,” or Florida terrapins, as gourmet food (Porter 1943:10-15).

|

| John Jefferson, Grandson of John Horse Institute of Texan Cultures, 68-932 |

His grandson, John Jefferson, became a trumpeter in the Seminole Scouts when the black Seminoles moved to Texas.

Gathering a determined band of Indian and maroon warriors, Wild Cat expanded his military operations to the remote areas of south Florida, whereupon the army sought to negotiate a treaty with the Seminole Nation. Under terms of the agreement, the Seminoles would turn themselves in along with their allies (black slaves or maroons) to emigrate west of the Mississippi. An agreement was reached in 1833 in which some of the Seminoles agreed to become part of the Creek Nation that had been established in Indian Territory (Mulroy 1993:27). However, Wild Cat and his band continued their guerilla warfare against installations and communities from base operations in the Big Cypress Swamp through 1840. Finally, the army’s patience wore thin and, sensing that Wild Cat never intended to capitulate, they seized him and threatened his life unless the rest of his band surrendered for deportation to Indian Territory. By 1841 the majority of the Seminoles had reported to emigrate, with the exception of a few holdouts in remote sanctuaries such as the Everglades (Wickman 1991:97).

The U.S. Army’s attempt to resettle the Florida Indians and blacks in Indian Territory was doomed from the start, since they were forced by the Tripartite Treaty of 1845 to share land with the Creeks (Evans 1990). Terms of the treaty also stipulated that Seminole slaves were to be restored to their masters, a source of rancor for the Creeks, who resented the modified form of slavery practiced by the Seminoles within the Creek Nation. The independence of the Seminole maroons also created alarm among the Creeks, who feared insurrection among their own slaves. John Horse, for example, preceding Wild Cat into the Indian Nation, had prepared a separate settlement for his group at Wewoka, according to previous Florida custom. The situation worsened when the Creek council issued a proclamation that no enclaves of freed blacks or Seminole maroons would be permitted to live in the Creek Nation or to bear arms. Thus the maroons were threatened with slavery and loss of property again (Mulroy 1993:41).

Wild Cat immediately regretted having left Florida. He knew that one small group of Seminole Indians in Florida had steadfastly held on to their lands, despite moneyed entreaties and threatened reprisals by the U.S. Government. After seven years his band was still unhappy with their assigned lands in Indian Territory, complaining that they were devoid of game, thus forcing them to become more dependent on the Creeks. The situation worsened when proslavery Seminole Jim Jumper (Micco Nutchasa) was chosen head chief over Wild Cat (Swanson 1985b:52-54). Licking his wounds, Wild Cat was invited to visit Texas as a representative of the Seminoles in a diplomatic peace-making initiative with the Comanches, Kiowas, Caddos, Wichitas, and Kickapoos. Ever conscious of his demotion as chief of the Seminoles, he quickly realized the opportunity to create an Indian confederacy or a Mexican colony to counter American expansion and Creek intolerance. Black Seminole legends say that John Horse also had traveled to Mexico to investigate the possibility of relocating.

Relocation to Mexico was appealing; not only did Mexico disallow slavery, but also a Mexican emissary had already approached the Seminole group about colonization (Mulroy 1993). Wild Cat and John Horse saw no options left. In 1849, after storing up supplies such as food and ammunition, a small band of Seminoles, maroons, and newly recruited black Creek and Cherokee runaways began a desperate migration south to northern Mexico (Pingenot 1994:195-96; Porter 1951:4). The trip would last one year.

THE TRIP

This trip was organized and led by Wild Cat and John Horse (see Woodhill 1937). During this trek slave hunters constantly chased the black Seminoles in the midst of Seminoles, Kickapoos, and other runaway blacks.

|

| Alice Fay Lozano, Black Seminole Elder |

Alice Fay Lozano, who grew up in Nacimiento, Mexico, recalls her great-great-grandmother Rose talking about this trip (Mock 2000).

“I was about nine years old when my great-great-grandmama [Rose] was with us. She probably wanted to talk, but my grandmama [Amelia] wouldn’t let her talk to us. When she would go somewhere, Rose would cry and tell us about the trip…. I remember Rose pretty well. She cried and cried. She said, ‘Oh baby, if you went through what we went through, you would cry too.’ She came from Florida to Indian Territory. She would get pretty sad and cry because they had to travel a long way...a year passed...crossed river with the whole group, got tired, it rained, The wind would get cold. Slave hunters always after them.”

Here we read the momentous event as described by a participant known only as Becky Simmons (Foster 1933, [reworded for accessibility]).

|

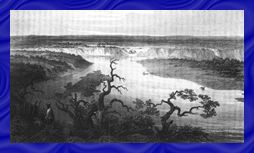

| Rio Grande near

Eagle Pass, Texas Institute of Texan Cultures, 72-363 |

Soon, Wild Cat said that he found a good place. We crossed first [women and children]. Then the men crossed after us. There was a raft made out of three logs tied together, which we crossed on. It was a good ride. The men took long sticks to guide the raft across the river. I remember that time. The children were about to cry out ’cause they were sleepy, and the old ones were scared that they were going to start bawling out before we got over. Wild Cat, he is fast and quick. He does things quick. The Mexicans did not know that we were over there. John Horse [Gopher John] told them when we were ready to tell the Mexicans that we were there.

Twenty days later the group of Seminoles, black Seminoles, and Kickapoos signed an agreement with Mexican authorities at Piedras Negras giving them supplies, provisions, and title to lands, or sitios, in the state of Coahuila (Amos and Senter 1996; Mulroy 1993). Both maroons and Indians were expected to act as an effective deterrent to other Indian raids along the Mexican border. Another requirement was that they become Catholics and adopt Spanish names. Eventually, both groups would settle in a small community, Nacimiento, at the headwaters of the Rio San Juan Sabinas.