Wakulla Through TimeFor more than 12,000 years humans have been drawn to Wakulla Spring for its cool, clear waters. Learn about Wakulla Spring's rich history from the prehistoric to the present. |

|

© Dean Quigley |

12,000 - 8,000 B.C.Florida's First PeopleArchaeological finds at Wakulla Spring, including early stone blades and Clovis spear points, are evidence of humans using the spring an estimated 12,000 years ago. Fossilized remains of mastodon and other prehistoric animals demonstrate that the spring attracted plentiful game for early nomadic people. During this time period the climate was much drier and some believe that Wakulla Spring was little more than a large sinkhole. |

© Dean Quigley |

8,000 B.C.- 1,000 A.D.Climate Change and Human SettlementA warming climate resulted in sea level rise and wetter and hotter conditions. Humans became less nomadic and settled close to places like Wakulla Spring, which provided an abundance of water and fish and game. Middens, prehistoric refuse heaps, and other archaeological finds including shells, tools, spear and arrowhead points and other projectiles, are evidence that Wakulla Spring supported small settlements of people over thousands of years. |

© Dean Quigley |

1500s Apalachee IndiansThe Apalachee Indians lived in the Panhandle region from Ochlockonee River to the Aucilla River in the east. The Apalachees were farmers, creating settlements throughout the region with the largest in the Tallahassee area. They were believed to number 50,000 before the arrival of the Spanish, however diseases brought by Europeans and conflicts with the Spanish greatly diminished their numbers. |

© Florida State Archives |

1528 Panfilo de NarvaezPanfilo de Narvaez, on an ill-fated quest for gold and riches in the province of "Apalachen," was the first Spanish explorer credited with exploring the Wakulla Springs area. After finding no gold and encountering fierce resistance from the Apalachee Indians, he and his starving group of men made their way to the coast where they fashioned crude rafts in an attempt to return to Cuba. Narvaez perished along with most of his remaining soldiers. |

© Florida CIT |

1656 Spanish MissionsLocated in Tallahassee, the Mission San Luis de Apalachee was the western capital of the Spanish Mission system in La Florida. These missions were established to Christianize the Indians and bring them under Spanish control. Trade routes with other missions and Fort San Marcos de Apalachee likely included the Wakulla River. In the 1700s Mission San Luis was attacked by English colonists and Indians from outside of Florida, eventually driving the Spanish and Apalachee Indians from the Tallahassee area. |

|

1804 Forbes PurchaseA trading company called Panton and Leslie negotiated a deal with Creek and Seminole Indians to acquire a huge tract of land from the Apalachicola River to Wakulla River. The deal, later known as the Forbes Purchase, included Wakulla Springs but was not recognized by the U.S. Government when it acquired Florida from Spain in 1819. A 1935 Supreme Court decision eventually upheld the Forbes Purchase. By that time the land had been distributed to individual creditors who formed the Apalachicola Land Company. |

© Florida State Archives |

1850s Wakulla Attracts AttentionWord about Wakulla Springs spread as stories were published in regional journals and newspapers that described a magical spot in the woods where water gushed forth from the ground and the remains of mastodons could be seen in the spring basin. These observations led to one of the earliest underwater archaeological recoveries when George S. King, a professor from Newport, Rhode Island, retrieved mastodon bones like this lower jawbone from about 40 feet of water. |

|

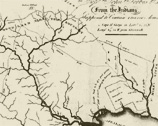

1863 Wakulla on the MapAlthough left off of many later maps, Wakulla Spring impressed some early cartographers enough to warrant space on maps of the region. |

© Florida State Archives |

Late 1800sWakulla Changes HandsBefore and after the Civil War, Wakulla Spring changed hands several times. Each new owner had plans to develop it as a resort and to market its natural beauty. Pictured here, an unidentified photographer in a boat photographs the spring and possibly one of the early owners. |

© Florida State Archives |

1900 A Public PlaceAlthough under private ownership, Wakulla Spring was always open to visitors drawn to the spring for picnics and boat rides. In this photo from 1900, visitors peer into the spring basin from a wooden dock, the predecessor to today's steel diving platform. |

© Florida State Archives |

1918 Exploring Nature at WakullaMany naturalists and early "ecotourists" were drawn to Wakulla Spring and River for unique wildlife experiences. Notes made on this photograph indicated that this couple explored the Wakulla River and spotted an ivory-billed woodpecker, believed to be extinct today. |

© Florida State Archives |

1925 Tourism at WakullaReal estate developer George T. Christie purchased Wakulla Spring and began exploiting it as a true tourist attraction. Christie built boathouses and established glass-bottom boat tours as a Wakulla Spring tradition. Pictured second from left, Christie coordinated a major recovery of mastodon remains in 1931 and turned the find into a public relations event for the spring. |

© Florida State Archives |

1934 Edward Ball Buys WakullaDespite his efforts to turn Wakulla Spring into a tourist attraction, Christie failed and was forced to sell the property in 1934. Edward Ball, brother-in-law of Alfred I. duPont and an influential Florida businessman, bought Wakulla Spring and 4,000 acres of land surrounding the spring. Ball immediately launched plans to build Wakulla Springs Lodge. |

© Florida State Archives |

1937 Wakulla Lodge OpensBuilt in a Mediterranean Revival style and rumored to cost in excess of $75,000, Wakulla Lodge was completed. The lodge opened to positive reviews and marked the realization of a dream for many area residents who wanted to see Wakulla Spring turned into a world-class tourism destination. |

© Florida State Archives |

1939 Newton PerryBall hired Newton Perry, a famous swim coach, to manage Wakulla Lodge. Perry was responsible for helping bring Hollywood film studios to Wakulla Spring. He also created several promotional underwater films highlighting the clarity of Wakulla's water, including this underwater "picnic." The short films were shown in theaters between feature films. |

© Florida State Archives |

1940s Tarpon ClubThe Tarpon Club, the synchronized swimming team from Florida State College for Women (now Florida State University), trained at Wakulla Spring. Wakulla Manager Newton Perry lured the team to participate in promotional activities including a short film titled "Campus Mermaids." |

© Florida State Archives |

1941 Tarzan at WakullaThe first Tarzan movie, featuring Olympic champion swimmer Johnny Weissmuller, was filmed at Wakulla Spring. Scenes from the classic Tarzan movies, "Tarzan's Secret Treasure" and "Tarzan's New York Adventure," were shot throughout the park and included several locals as stand-ins and the use of elephants and monkeys on the set. |

© Wakulla Springs State Park |

1943 Wakulla Lodge BurnsThe Wakulla Lodge roof caught fire and burned. The quick action of several Army officers housed at the lodge and the fire resistant construction of the building prevented a total disaster. A cameraman who happened to be staying at Wakulla Spring captured the action on his movie camera. The film became a home movie favorite of Ed Ball. |

© Florida State Archives |

1953 Creature from the Black LagoonMany scenes from the classic film "Creature from the Black Lagoon" were filmed at Wakulla Spring. Local Tallahassee resident Ricou Browning played the creature in the underwater scenes. This launched a career in entertainment that had Browning working on the original "Flipper" and "Sea Hunt" series as well as a number of other Hollywood movies. |

|

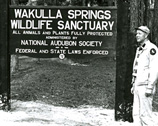

1963 National Audubon SocietyWakulla Spring's 4,000 acres were designated as a wildlife and bird sanctuary and leased to the National Audubon Society to manage. This agreement was part of Ed Ball's desire to protect the land around the spring and river. The relationship lasted for about seven years. |

|

1966 National Natural LandmarkThe Secretary of the Interior designated Wakulla Spring as a National Natural Landmark. This designation, administered by the National Park Service, has been given to fewer than 600 locations throughout the U.S. and recognizes the best examples of biological and geological features in both public and private ownership. |

|

1971 Fence ControversyLocal residents challenged Ed Ball in court over a fence placed across the Wakulla River some years earlier. In an effort to protect the spring and wildlife sanctuary, Ball had the fence installed across the river. The controversy and case continued for several years before the court decided that the portion of the river within the park was not navigable and therefore owned by Ball. |

|

1973 Peak Water FlowOn April 11, peak water flow at Wakulla Spring was measured at 1.23 billion gallons in a single day. Wakulla Spring's flow today averages about 250 million gallons per day. |

|

1976 Airport '77 FilmedScenes from the movie Airport '77 starring Jack Lemmon were filmed at Wakulla Spring. The filming included placement of an elaborate 70-foot mockup of a 747 jet into the spring basin. This was one of the last Hollywood films shot at the Wakulla Spring. |

© Florida State Archives |

1980 Nature Tourism ReignsWakulla Spring's reputation as a unique natural feature is firmly established and continued to draw visitors from afar. Ed Ball resisted pressure to develop Wakulla Spring as a large tourist resort like Silver Springs and Cypress Gardens. |

|

1981 Ed Ball DiesEd Ball, one of Florida's most influential business leaders, dies at the age of 93. Ball passed on most of his assets and ownership of Wakulla Spring to the Nemours Foundation, a charitable organization for children that was started by Alfred I. duPont, Ball's brother-in-law. |

|

1986 State Purchases Wakulla SpringFlorida's Governor Graham identified Wakulla Spring as a high priority natural resource for acquisition, and following a brief negotiation the State of Florida purchased the spring and added it to the state park system as the Edward Ball Wakulla Springs State Park. |

© Wes Skiles |

1987 Scientific ExplorationThe state's purchase of Wakulla Spring opened the door to new scientific exploration. The U.S. Deep Cave Diving Team penetrated and mapped 2.3 miles of Wakulla's cave system and tested a new "rebreather" technology that greatly extended underwater time for divers. |

|

1993 National Register of Historic PlacesWakulla Springs State Park was added to the National Register of Historic Places in recognition of its significance as a historic and archaeological site. |

© Wakulla Springs State Park |

1995 Major Archaeological FindDuring renovations at Wakulla Springs Lodge, State Archaeologist Calvin Jones unearthed a large stone blade and Clovis spear points used during the Paleo-Indian period. The discovery confirmed that humans had used the site of the lodge for an estimated 12,000 years. |

© Bob Thompson |

1997 Hydrilla Invades Spring BasinThe invasive weed hydrilla appeared in the Wakulla Spring basin creating new management challenges for state park personnel. |

© David Rhea |

1998 Record Breaking DivesMembers of Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) and the Woodville Karst Plain Project established a new world record for underwater cave penetrations by pushing nearly three and a half miles beyond the entrance to Wakulla's cave. Their work helped establish Wakulla Spring as one of the largest spring systems in the world. |

|

1999 Land Dispute SettledA protracted legal battle ended over the proposed commercial development on a 25-acre parcel near the entrance to Wakulla Springs State Park. The legal case ended with an agreement by the state to purchase the land, and it helped focus attention on the need to protect land in Wakulla Spring's springshed. |

© Wes Skiles |

1999 - 2000 Mapping of Wakulla CaveTwo separate expeditions by the U.S. Deep Cave Diving Team and members of the Woodville Karst Plain Project (WKPP)were undertaken resulting in the creation of detailed 3-D maps of the cave system. WKPP members pushed three and a half miles beyond the cave's entrance and collected important data about the extent of Wakulla's cave system, which would help bolster protection efforts for Wakulla Spring. |

|

2000 Land AcquisitionMore than 3,000 acres of land in Wakulla Spring's springshed was added to the inventory of Wakulla Springs State Park. The acquisition included Cherokee Sink, a large sinkhole and popular Wakulla County swimming area. |

|

2004 Study Confirms Stormwater LinkIn an effort to identify vulnerable areas of Wakulla Spring's springshed, dye trace studies painted a clear picture of how water flows from the north underground to Wakulla Spring. The studies demonstrated that much of Tallahassee's stormwater enters sinkholes just south of the city where it flows underground and emerges at Wakulla Spring. The research broadened understanding of the need to protect land in Wakulla Spring's springshed. |

Acknowledgements:The primary resource for this historical timeline was "Watery Eden: A History of Wakulla Springs" by Tracy Revels. Published in 2002 by the Friends of Wakulla Springs State Park, the book can be purchased at Wakulla Springs State Park. |