Wednesday, October 10 - Part 2

Click on these photos for a higher resolution.

They will be slow to load with a dial-up connection.

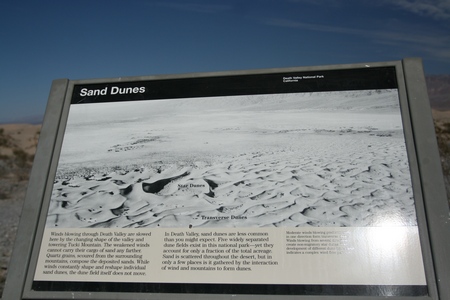

Just south of Stovepipe Wells lies Mesquite Dunes, one of Death Valleys' 5 dune fields.

Death Valley's most accessible sand dunes are just a few miles from Stovepipe Wells. Tucked into Mesquite Flat in the north end of the park, these dunes are nearly surrounded by mountains on all sides. The primary source of the dune sands is probably the Cottonwood Mountains which lie to the north and northwest. The tiny grains of quartz and feldspar that form the sinuous sculptures that make up this dune field began as much larger pieces of solid rock.

Source: USGS

Just in case you miss them.

There are a couple of requirements for dune formation. One of these requirements is wind. Sand is blown by wind until it reaches an obstacle. In the case of Death Valley, obstacles are mainly mountains! Wind doesn't have enough energy to blow the sand-sized particles up and over the mountains, as the wind-energy decreases they drop their load and deposit them where we see it today. It takes many wind storms to accumulate the amount of sand we see in Death Valley’s dune fields.

Source: NPS

Here are some nice dune photos.

The so called Devils Cornfield near Stovepipe Wells

For Bill, in case he forgets his last name.

Deep, hot and dry. One can only image how the pioneers managed to survive under such harsh conditions.

Timbisha Shoshone, the Native American people who have lived in Death Valley for centuries, did the most logical thing when summer arrived -- they left for higher and cooler country. In the early history of the valley, almost everyone else followed their example. Only a few hardy souls stayed behind to face the intense heat of summer. Miners working the Keane Wonder Mine in 1908 complained that even eating became difficult; the silverware was too hot to handle. Original caretakers of the Greenland Ranch at Furnace Creek slept in the irrigation ditches and devised a water-wheel powered fan to cool themselves Today, with electric air conditioners and evaporative coolers, we human beings can find shelter from Death Valley's heat.

Source: Desert USA

Since ancient times, borax and other borate minerals have been used in the Near East and Asia as an antiseptic, a washing agent, and welding flux. Europeans were not introduced to borates until the 13th century, when Marco Polo returned from Asia with borax crystals. However, borax remained a rare commodity until rich lake bed deposits were found in California and Nevada in the 1850's and 60's.

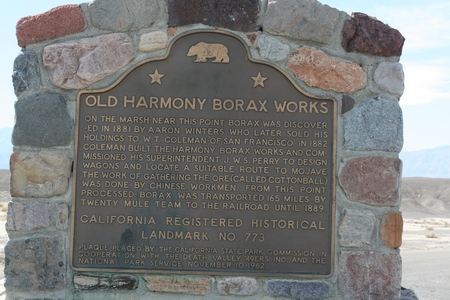

By the 1870's, an expanding market for borax motivated miners to search for new deposits in the desert playas of California and Nevada. In 1881, Rosie and Aaron Winters discovered borax on the Death Valley playa at the mouth of Furnace Creek wash in Death Valley.

Source: USGS

Remains of one of the adobe brick structures at Harmony Borax.

After borax was found near Furnace Creek Ranch (then called Greenland) in 1881, William Tell Coleman built the Harmony plant and began to process ore in late 1883 or early 1884. When in full operation, the Harmony Borax Works employed 40 men who produced three tons of borax daily. During the summer months, when the weather was so hot that processing water would not cool enough to permit the suspended borax to crystallize, Coleman moved his work force to the Amargosa Borax Plant near present day Tecopa, California.

Getting the finished product to market from the heart of Death Valley was a difficult task, and an efficient method had to be devised. The harmony operation became famous through the use of large mule teams and double wagons that hauled borax the long overland route to Mojave. The romantic image of the "20-mule team" persists to this day and has become the symbol of the borax industry in this country.

The Harmony plant went out of operation in 1888, after only five years of production, when Coleman’s financial empire collapsed. Acquired by Francis Marion Smith, the works never resumed the boiling of cotton ball borate ore, and in time became part of the borax reserves of the Pacific Coast Borax Company and its successors. On December 31, 1974, the site was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

At present the Borax Works plant consists of a four-level ruin situated against a hillside. There are remains of buildings, machinery, tanks, piping, and waste tailings. In addition to the plant proper, a nearby town site contains remnants of buildings and trash dumps relating to the company settlement. The entire complex is referred to as "Harmony Borax Works," or simply as "Harmony."

Source: digital-desert.com

In the Furnace Creek area, borates were deposited in the remains of old lake beds. Later, partial alteration and solution of these veins by groundwater moved some of the borates to the Death Valley floor where evaporation has left a mixed crust of salt, borates, and alkalies.

When Aaron and Rosie Winters filed claims on the borax deposits near Harmony in 1881, borax was so precious it was called " white gold". It was used in pottery glazes for china and porcelain enamel, as a flux and deoxidizer in welding, soldering, brazing, smelting and refining metals, as a mild antiseptic, soap and laundry aid, as a food preservative-- to name a few of its uses. Once William T. Coleman bought the claims and started up his mining operation in 1882, he faced numerous problems. J.W. S. Perry designed the transportation system of 20 mule teams to haul the borax along the rugged 165 mile journey.

Getting a road through the valley floor in the terrain near the Devils Golf Course was achieved by sending the Chinese laborers with sledgehammers to beat a path for the 20 mule team wagons. The workers mined the borax by raking it from the valley floor and from there it was brought to the processing plant where it was melted down and hardened again before being hauled out. From 1883-1888 the famous mule teams hauled borax out of Death Valley. At Harmony Borax works one can see the old processing plant and a 20 mule team wagon. A paved path takes you around the exhibits from the parking area where you can imagine what the lives of the workers would have been like.

Source: Death Valley Chamber of Commerce

The following is from a brochure published by Kerr-McGee Chemical Corporation in 1989. It describes the history of the Trona Chemical plant from the beginning up until about the time it was sold to North American Chemical Corporation

Lured by the Gold Rush of ’49, John W. Searles and his brother Dennis sailed from New York to California in search of precious metals. Like most prospectors, they found plenty of hardship and very little gold. Unlike most other prospectors, they found treasure of another kind.

While searching for gold near the Panamint Mountains in 1862, John Searles came across a crusty dry lake bed. Noticing crystals shimmering in the sunlight, he scooped up a handful and tucked them in his oar sack, unaware that he had discovered the worlds richest deposits of chemicals.

Ten years passed. Then in Nevada, Searles saw Francis "Borax" Smith recovering borax from similar crystals. Suddenly recognizing the value of the dry lake he had found in California Searles backtracked. His find was worth more than the gold that had eluded him.

Source:Trona on the Web

The crusty layer nearly supported my weight.

Borate deposits form a hard crust. These were chipped and dug by laborers and transported to the processing plant. The work was performed as long as the temperature remained below 120 degrees. Above 120 degrees the borates, which were mixed with hot water to create "liquor" would not precipitate out when cooled to form the crystals.

While boron is ubiquitous in the environment, substantial deposits of borates are relatively rare.

Borates are minerals formed when boron, a naturally occurring element, combines with oxygen and other elements. It takes vast amounts of borate minerals concentrated in one place to make a deposit worth mining. It also takes millions of years for the deposit to form.

In between the access road to the Borax works and the ruins of the refinery was a low wide ditch or wash. The bottom of the ditch showed clear evidence of water - but from where it came I have no idea.

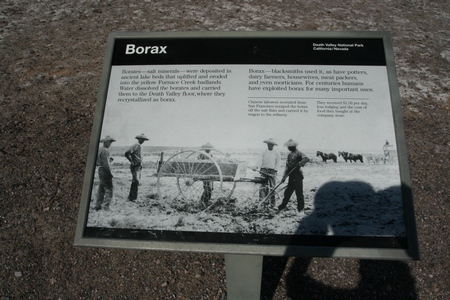

One of the numerous interpretive signs at the Old Harmony Borax ruins. Below is text from the sign.

“Chinese workers recruited from San Francisco scraped the borax of the salt flats and carried it by wagon to the refinery. They received $1.30 per day, less lodging and the cost of the food they bought at the company store.”

The above made me think of the West Virginia coal miners of the same period. A coal miner in West Virginia generally lived in a company town. He woke up in a company bed situated in a company house. He washed himself with water drawn from a company well and ate breakfast prepared with food bought at the company store. Everything consumed or used by his family came from the company, purchased on credit. The credits used during the pay period only rarely failed to add up to less than the paycheck (paid not in United States currency, but company script.) In debt from his first day on the job, the entire system was geared towards keeping him and his family that way.

I have no doubt the Chinese workers at the borax works lived a similar life.

After borax was found near Furnace Creek Ranch (then called Greenland) in 1881, W. T. Coleman built the Harmony plant and began to process ore in late 1883 or early 1884. When in full operation, the Harmony Borax Works employed 40 men, who produced three tons of borax daily. What little evidence remains indicates that the bulk of this labor force was composed of Chinese workers. The Chinese laborers gathered the impure chunks of mineral from the valley floor and loaded them into one-horse carts for transport to the borax plant.

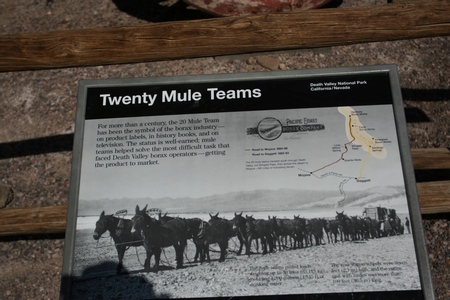

This image of twenty mule team, the symbol of the industry, was seen every week by the many Americans who watched the TV Western “Wagon Train”, including me. The show ran from 1957 to 1965 and I remember it being a show we never missed.

The twenty mule teams solved a transportation problem: between 1883 and 1888 they hauled more than twelve million pounds of borax from remote and inaccessible Death Valley to the railroad at Mojave.

When the Harmony Borax Works was built in 1882, teams of eight and ten mules hauled the ore. But with increased production, the first teams of twenty mules were tried. Stretching out more than a hundred feet from the wagons, the great elongated teams immediately proved a dependable means of transportation.

Source: LetsGoSeeIt.com

According to legend, Harmony Borax local superintendent J.W.S. Perry and a young muleskinner named Ed Stiles thought of hitching two ten-mule teams together to forms a 100-foot-long, twenty mule team. The borax load had to be hauled 165 miles up and out of Death Valley, over the steep Panamint Mountains and across the desert to the nearest railroad junction at Mojave. The 20-day round trip started 190 feet below sea level and climbed to an elevation of 2,000 feet before it was over.

Built in Mojave for $900 each, the wagons' design balanced strength and capacity to carry the heavy load of borax ore. Each wagon was to carry ten tons — about one-tenth the capacity of a modern railroad freight car. But instead of rolling on steel rails over a smooth roadbed, these wagons had to grind through sand and gravel and hold together up and down steep mountain grades. Iron tires — eight inches wide and one inch thick — encased the seven-foot-high rear wheels and five-foot front wheels. The split oak spokes measured five and one-half inches wide at the hub. Solid steel bars, three and one-half inches square, acted as the axle-trees. The wagon beds were 16 feet long, four feet wide and six feet deep. Empty, each wagon weighed 7,800 pounds. Two loaded wagons plus the water tank made a total load of 73,200 pounds or 36 1/2 tons.

Source: Borax: The Twenty Mule Team

Remains of one the boilers which was used to make the borax liquor.

There were always other tourists around - most seemed to be from France and Germany.

This is the Furnace Creek Inn and Ranch Resort.

In the 1920s, the Pacific Coast Borax Company followed the lead of the successful Palm Springs Desert Inn and entered the tourism business by building a magnificent Inn for guests to enjoy the rare beauty of Death Valley. Los Angeles architect Albert C. Martin designed the mission-style structure set into the low ridge overlooking Furnace Creek Wash. Adobe bricks were hand made by Paiute and Shoshone laborers. Spanish stonemason Steve Esteves created the Moorish influenced stonework, while meandering gardens and Deglet Noor palm trees were planted.

The Furnace Creek Inn opened on February 1, 1927 with 12 guest rooms, a dining room and lobby area. Room rates were $10 per night and included meals.

Source: Hotel Online

The National Park Service, in all it's wisdom had contracted the operations to Xanterra Parks & Resorts.

This means you get to pay over $200 (starting rate) for a room. Apparently the policy makers at the NPS do not realize some folks don't even have weekly paychecks of that amount.

The message: Come stay with us if you are priveleged and wealthy.