Saturday, January 31

Geary and I had a very busy day. It started out with a quick breakfast of muffins from Joseph's Storehouse and Bakery. We then proceeded to Geary's office at the Edwards Aquifer Authority and then went on to the offices of the San Antonio Water System (SAWS) and then on (and on and on and on) from there.

Click on these photos for a higher resolution. Will be slow with dial-up connection.

San Antonio Water System puts on periodic outreach and education programs for the public so as to better help users understand where their water comes from, how it gets to the tap and then what happens to it after it has been used. Greg Wukasch, Education Specialist for SAWS had organized today's event. He also presented the information on how SAWS collects and distributes fresh water and then gave everyone a first hand look at how sewage is processed and what the final stop is.

The job of explaining where the water comes from and how it gets there - before SAWS ever touches it, was handled by Geary Schindel, who is the Chief Technical Offices for the Edwards Aquifer Authority.

In the photo above Geary explains the process of how surface water enters, through various ways, the vast limestone storage area that is the Edwards Aquifer. This huge chunk of limestone was formed from the shells of dead marine life which lived in a shallow sea covering the area. The limestone aquifer is about 8,000 square miles and includes all or part of 13 counties in south-central Texas.

After Geary's presentation we all boarded a bus for a field trip to Stone Oak Park which is home to both Bear and Cub Cave.

Here, Geary talks about safety before our walk begins. For folks that have never been in a wildscape, he's telling them to watch where they stand so not to play with the fire ants, don't pet any black cats with white stripes, don't pick up any sticks with rattles on the end, and don't play with any large tan colored kitty cats.

This is the gated entrance to Bear cave. There is a 20' narrow shaft to the cave floor. Here, Geary explains how this structure is actually a former spring discharge point rather than the sink point.

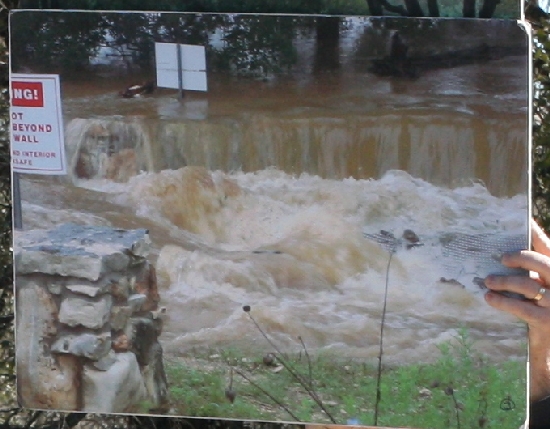

Here Greg Wukasch holds up a photo of flood water pouring into the cave entrance. This is one of the methods by which the aquifer is recharged.

To the right, you can just make out the steel mesh cave gate.

This is the entrance to Cub Cave which is within a few 100 feet of Bear Cave. Geary points out some of the features of the entrance and talks about cave biodiversity.

When these photos were taken the greater San Antonio was in a severe drought. This was the only sign of moisture I saw - condensation of the most cave air on this moss covered rock.

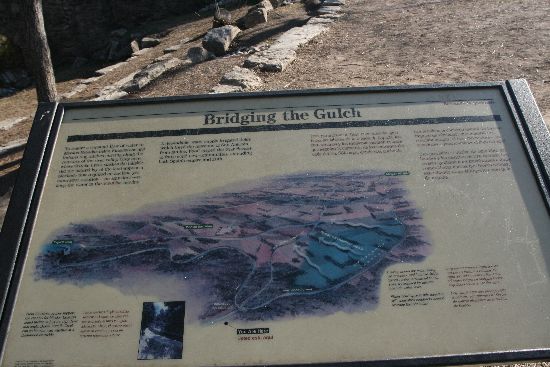

Every park I visited it the San Antonio area had excellent interpretive signage.

After we got back from Stone Oak Park we had a delicious box lunch from Joseph's Storehouse Restaurant & Bakery which was provided by SAWS. Greg Wukasch then gave us a thorough and informative overview of how SAWS distritbutes the water and handles the waste. Afterwards everyone got back on bus for a tour of a freshwater pumping facility and sewage processing plant.

Geary and I opted out of this field trip as we had a busy day ahead of us.

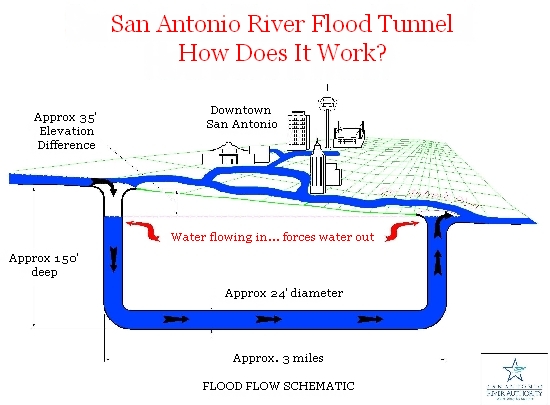

One of the things Greg Wukasch mentioned in his talk was the flood control project for the San Antonio River. It is a project of the San Antonio River Authority.

This is the gate at Josephine Street where the river enters the Tunnel.

The San Antonio River flood diversion tunnel is approximately 16,200 feet long with precast concrete segmented liners of 24 feet, 4 inches inside diameter. The tunnel starts near Josephine Street where the tunnel inlet shaft is constructed adjacent to the existing channel (See Figure 2 for the tunnel's route).

The inlet shaft is 24 feet, 4 inches in diameter dropping approximately 118 feet to the tunnel invert. The tunnel outlet shaft near Lone Star Boulevard is 35 feet in diameter and contains embedded piping for dewatering facilities. Two (2) 18 foot diameter maintenance shafts, three (3) 4 foot diameter ventilation shafts and two (2) 12 inch diameter hydraulic instrumentation shafts are provided at intervals along the tunnel length.

Source: San Antonio River Authority

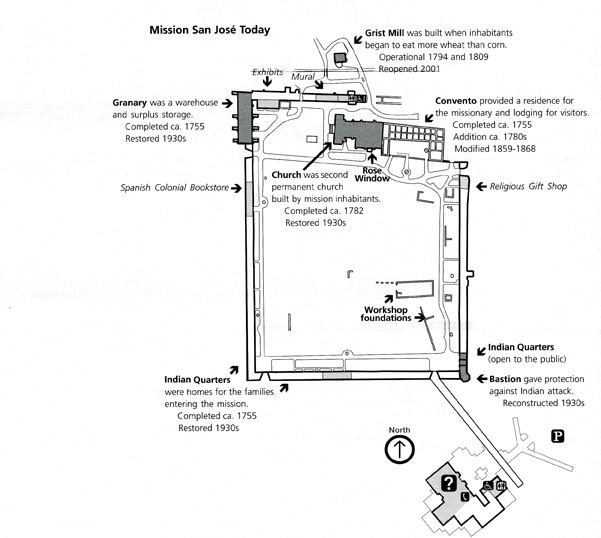

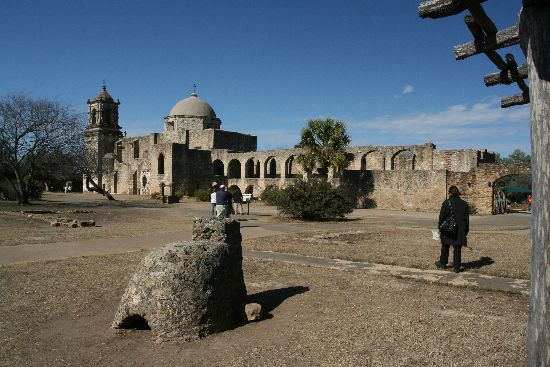

We then drove a short ways to San Antonio Missions National Historical Park. We stopped first at Mission San José y San Miguel de Aguayo (Mission San Jose) to talk to Ranger Mike who told us all about the Missions.

In the foreground is a stone oven used for baking. The Convent is on the right, then the curch, bell tower and church entrance.

In 1719, Father Margil de Jesús, a seasoned Franciscan missionary, was at Mission San Antonio de Valero (today’s Alamo), awaiting the opportunity to re-establish missions in east Texas. Before too long, he saw need for another mission and wrote the Marqués de Aguayo, then governor of the Province of Coahuila and Texas, requesting permission to establish a second mission south of San Antonio de Valero. He felt he was prepared to establish this mission at once as he had necessary church goods with him, even a statue of Saint Joseph.

The Marqués agreed and founding ceremonies took place on February 23, 1720. Leaders of the three Indian bands were appointed governor, judge, and sheriff in the new mission community of San José y San Miguel de Aguayo. Father Margil entrusted the care of the project to Father Núñez and two soldiers.

The building of the limestone church, with its extraordinary Spanish colonial Baroque architecture and statuary began in 1768— the peak of this mission’s development. At that time there were 350 Indians residing in 84 two-room apartments. Based on Father Morfi’s description of what he saw here when he visited in 1777, Mission San José came to be known as the “Queen of the Missions.”

José in 1778 The Franciscan friars objective was to convert indigenous hunters and gatherers into Catholic, tax-paying citizens of New Spain. The Indians’ struggle for survival against European disease and raiding Lipan Apaches led them to the missions and to forfeit their culture. Everything changed for them: diet, clothing, religion, culture—even their names. They were required to learn two new languages, Latin and Spanish, as well as new vocations.

Their new roles and duties in the mission were very regimented. Church bells called them to mass three times a day. Following sunrise mass, families returned to their two-room quarters for corn atole (mush) and charque (jerky). After breakfast, the men and boys worked in the labores (fields), and in textile, tailor, carpenter, and blacksmith shops. They also worked as masons, weavers, acequia (irrigation ditch) builders, and at the lime kilns. Some took charge of the livestock at the mission’s ranch, El Atascoso, about 25 miles southwest of the mission.

The women and girls prepared food, swept the dirt floors, carded wool, and fished in the irrigation ditch outside the walls. Father Ramírez gave the Indian children religious instruction. Spanish and Indian mission officials met in the plaza to discuss community affairs. The bells rang out at noon, calling everyone back to the church for prayers. The main meal of the day was lunch, perhaps a bowl of goat stew and fresh baked tortillas. The afternoon siesta followed the meal and most activity subsided for several hours. Mounted Indian sentinels, however, continually kept guard outside the walls.

Summoned by the bells, everyone returned to the church for evening worship. After supper, recreational time for singing, games, dances, storytelling, and drama filled the evening. At dark, all retired to their raised beds of buffalo hides. The next work day began at sunrise as the mission Indians were again called by the bells into the church for mass.

Source: National Park Service

The bell tower. I wonder what the round structure was for?

Water well with the Convent in the background.

This is the Rose Window. The Indians that wanted to partake in the Mass would stand outside if they weren't baptized yet. There is now an iron fence around the this window to prevent contact.

The Rose Window or Rosa's Window

The Rose Window is known as the premier example of Spanish Colonial ornamentation in the United States. Its sculptor and significance continue to be a mystery. Folklore credits Pedro Huizar, a carpenter and surveyor from Mexico, with carving the famous window as a monument to his sweetheart, Rosa. Tragically, on her way from Spain to join him, Rosa was lost at sea. Pedro then completed the window as a declaration of enduring love.A less colorful theory, but more likely, is that the window was named after Saint Rose of Lima, the first saint of the New World.

Source: NPS

The entrance to the prayer sanctuary of the church.

Detail at base of entry arch.

Rootin' tootin' shootin' Texans! Some of them can't go anywhere without "packing a piece".

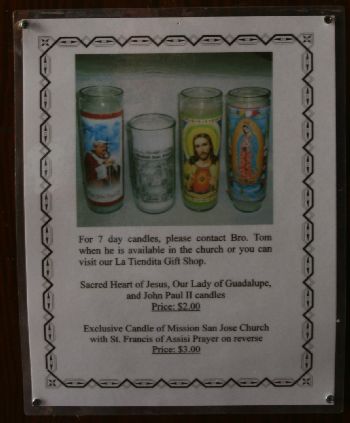

These 7 day candles are very popular in the west. Some of them have very bizarre scenes of torture and execution on them.

Holy water vessel just inside the sanctuary.

A quiet and private place for reflection and prayer - when all the tourists are not walking about and chatting.

San José y San Miguel de Aguayo Mission, one of the five Spanish missions in San Antonio, was founded in the early eighteenth century as a result of a shift of missionary effort from East Texas to South Texas.

In 1719 war between France and Spain resulted in the temporary withdrawal of Spanish missionaries from the East Texas missions. Father Antonio Margil de Jesús, president of the Franciscans of the College of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de Zacatecas, went to San Antonio, where, on December 26, 1719, he requested that a new mission be founded.

The Marqués de San Miguel de Aguayo, governor of Coahuila and Texas, responded by issuing a decree on January 22, 1720, which authorized Capt. Juan Valdez, alcalde at the presidio of San Antonio de Béxar, to select a suitable site for the mission. On February 23 Valdez, assisted by Capt. Lorenzo García, presented a large tract of land on the east bank of the San Antonio River to Margil, downstream from San Antonio de Valero Mission.

The land was assigned to about 240 Indians from an area not far south of San Antonio, mainly Pampopa, Pastia, and Sulujam, the first bands to reside at the mission. Margil entrusted their care to fathers Agustín Patrón and Miguel Núñez de Haro. Núñez moved the mission across the river probably before 1730, the year Brig. Gen.

Pedro de Rivera y Villalón officially noted that the church and other structures were now on the west bank. After a disastrous epidemic in 1739 reduced the number of Indian inhabitants to forty-nine, the mission was moved to its present location on higher ground, more than one-half mile from the former site.

Numerous Indian groups were represented at San José. Because the baptismal, marriage, and burial registers-the most reliable sources of information about the identities of Indian inhabitants-are apparently lost, probably no more than half of the groups represented can be identified. Of the twenty-one groups known to have stayed at San José, many were Coahuiltecan, though other cultural and linguistic groups were also represented. Among the Coahuiltecans were Aguastaya, Aranama, Camama, Cana, Chayopin, Mayapem, Mesquite, Queniacapem, Saulapaguem, Tacame, Tenicapem, and Xuano Indians.

The Cujans were a Karankawan group, the Eyeish were Caddoan, and the Lipan Apaches were Athabascan. Also present were Indians called Borrado and Pinto, collective designations that Spaniards gave to groups of diverse origins who originally lived south of the Rio Grande in Nuevo León and Tamaulipas.

Displacement, fragmentation, population decline, and Apache hostility often prompted Indians to seek refuge among the Spaniards. The Spanish themselves-notably through such massive colonization efforts as that of José de Escandón-exacerbated the material problems that encouraged the Indians to move to the missions.

The mission was to acquaint the Indians with Christian teaching, European values, and vocational skills and to convert them to useful citizens of the empire. Neophytes learned the basic tenets of Catholicism, arts and crafts, and music and singing. Juan Agustín Morfi wrote in the 1780s, "many play the harp, the violin, and the guitar well, sing well, and dance the same dances as the Spaniards." ~Gilberto R. Cruz

Main entrance to the church.

Above is the reconstructed scene of Mission San Jose by artist Ernst Schuchard referred to below.

The San Antonio missions have been the subject of historical and archeological research for decades. At left, a reconstructed scene of Mission San Jose by artist Ernst Schuchard helps bring the color and cultures of the Spanish mission to life. Top right, archaeologists from the Center for Archaeological Research at UTSA conduct excavations at the San Jose grist mill under the watchful eye of visitors.

Bottom right, an array of artifacts recovered from mission sites, including a crucifix, chipped-stone arrow points made by mission Indians, and fragments of an early blue and white majolica bowl. Detail of painting by Ernst Schuchard, courtesy of the Daughters of Republic of Texas Library. See full painting. Photos courtesy of Center for Archaeological Research, University of Texas at San Antonio.

Photo taken just inside the entrance.

Doorway and ramada near the granary.

Another long ramada along the entrances to the Indian quarters.

The Spanish missions were not churches. They were Indian towns, with the church as the focus, where, in the 1700s, the native people were learning to become Spanish citizens. In order to become a citizen, they had to be Catholic; that is why the King of Spain sent missionaries to acculturate them.

Wall support arch along the granary wall.

The mill at San Jose was in use and grinding wheat by 1794. The mill is believed to be the oldest in Texas.

One of the most interesting things to me at the San José Mission in San Antonio is the Water Powered Gristmill. Built more than two centuries ago, the gristmill continues grinding away. Park ranger and head miller tells visitors, “We could grind 600 to 800 pounds of flour every day if we had to, just as they did years ago.”

When the European Priests first arrived in Texas to build the Missions the only type of bread they found was "Corn" bread. Corn can be milled by hand but to mill the harder wheat grain required some type of mechanical mill.

A logical addition to the extensive irrigation canal system from the San Antonio River, was a water powered mill. The mill at San José is not a technological wonder even when compared to water powered mills of that day. A gate directed water into a deep tub. Water from the tub was throttled with a smaller gate out through a small wooden pipe onto the horizontal vanes of a water wheel attached to a vertical shaft.

Source: Texas Bob Travels

This shows the grain "shoe" which, when moved by the turning of the wheel, continuously drops small amounts of grain through the hole in the top of the wheel for milling.

Before and after.

Detail of the ceiling/roof of the grist mill.

The wood components of the ceiling in the Grist Mill are called vegas and latillas. The vigas are the lower, heavy beams and the latillas are the upper, smaller cross materials. The vigas are supported the walls of the building. Traditionally clay, rock, and/or plant materials would be placed above the latillas for the outer roof material.

The type of construction is usually referred to as a viga ceiling, or vigas and latillas. It is still common in the southwest, and is a pricey feature in new construction but without the clay and rocks.

The vigas and latillas in the grist mill are modern, capped with a metal and asphalt roof. The wood material is ash juniper, called around here "cedar." In the 1700s oak or cypress would have been used in this area for the vigas and maybe cedar for the latillas.

Source: Daniel Hollifield, Park Ranger: San Antonio Missions National Historical Park

Underneath the mill is the water inlet which powers the water wheel. It then turns the shaft to which the milling wheel in attached. The water comes from an acequia.

After leaving Mission San Jose Geary and I drove to Acequia Park to take a look at the watered Acequia and the Piedras Creek Aqueduct.

An acequia is a community operated waterway used in Spain and former Spanish colonies in the Americas for irrigation. Particularly in the Andes, northern Mexico, and the modern-day American Southwest, acequias (pronounced ah-SAY-kee-us) are usually historically engineered canals that carry snow runoff or river water to distant fields.

The Spanish word acequia comes from the Arabic "al saqiya" and means water conduit. The Arabs brought the technology to Spain during their occupation of the Iberian peninsula. The technology was adopted by the Spanish and utilized throughout their conquered lands.

Most acequias were established more than 200 years ago; many continue to provide a primary source of water for farming and ranching ventures in areas of the United States once occupied by Spain or Mexico.

Acequias are gravity chutes, similar in concept to flumes. Some acequias are conveyed through pipes or aqueducts, of modern fabrication or decades or centuries old (see transvasement). The majority, however, are simple open ditches with dirt banks. In many communities, the ditchbanks are important routes for non-motorized travel.

Known among water users simply as the Acequia, various legal entities embody the community associations, or acequia associations, that govern members' water usage, depending on local precedents and traditions. An acequia organization often includes "ditch riders" and a majordomo who administers usage of water from a ditch, regulating which water-rights holders can release water to their fields on what days.

Source: WikiPedia

Like anyplace with limited rainfall, water is the key to survival and prosperity. To ensure this the Spanish built an extensive irrigation network.

Barbara and Glenn Musser have a great web page for the San Antonio Mission with better photos and additional information.

After leaving the Mission area we headed south the 5 miles or so to Mitchell Lake Audubon Center. But, they closed at 4:00 and we were too late to gain entrance.

About Mitchell Lake Just south of downtown San Antonio, the Mitchell Lake Audubon Center is located on a 1200-acre natural area. This unique and beautiful bird haven consists of the 600-acre Mitchell Lake, 215 acres of wetlands and ponds and 385 acres of upland habitat. Located on the northern edge of the South Texas plains eco-region, it is not uncommon to see American White Pelicans by the hundreds resting among an assortment of waterbirds such as Northern Pintail, American Avocet, and Green Heron. Where, in the summertime, Painted Buntings and Orchard Orioles can be heard and seen off the porch of the beautifully restored 1910 home that is now the Mitchell Lake Audubon Center. The Center is nestled among a colorful garden of xeriscape plants that invites an assortment of birds, butterflies, and the occasional lizard.

Audubon has partnered with the San Antonio Water System (SAWS) to showcase this wonderful natural area and welcomes not only the nature enthusiast to its gates but also connects schoolchildren and families to this natural place. The Mitchell Lake Audubon Center provides science education for local K-12 schools with a special emphasis on 4th grade.

We then headed north to New Braunfels, about 40 miles northeast to another lake.

Here we are at Landa Lake in Landa Park.

This lake is quite unique as it in fed from the waters of Comal Springs.

This view reminded me very much of another spring fed body of water, theWacissa River in Florida, shown in the photo below.

The Wacissa River in Florida.

Towards the far end of Landa lake there are homes on the waters edge. As I understand it, the lake surface is restricted and can only be used by residents.

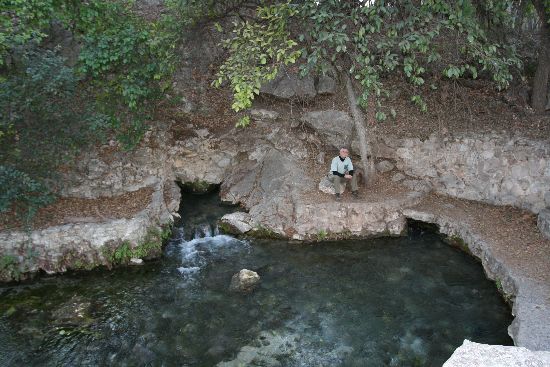

This is the main resurgence of Comal Springs.

The Comal Springs are the largest in Texas and the American southwest. Seven major springs and dozens of smaller ones occur over a distance of about 4,300 feet at the base of a steep limestone bluff in New Braunfels' Landa Park. The Springs and the Comal River below are home for a federally endangered species, the Fountain Darter. In Spanish, comal is a flat griddle used for cooking tortillas, so the name probably refers to the flat area below the bluff where the springs issue forth. The largest and most easily visited is the one shown at left, just west of Landa Park drive.

These springs were a favorite camping place for native Indian tribes for thousands of years, and many artifacts and burial mounds have been found. In the language of the Indians the Comal Springs were called Conaqueyadesta, which means "where the river has its source" (Ximenes, 1963). The Comal River arises entirely, except after major rains, from springs in this vicinity and flows for just over two miles through Landa Park and New Braunfels before confluencing with the Guadalupe River. It is said to be the shortest river in the United States.

Source: EdwardsAquifer.net

Here is the gorgeous, crystal clear water which feeds the lake and Comal River.

The Comal River became famous when Ripley's Believe It or Not featured it as the shortest river in the world. The 2.5-mile river rises from Comal Springs in Landa Park where it fuels a swimming pool, past Schlitterbahn, and meets the Guadalupe River in the heart of downtown New Braunfels. The Comal is more popular with tubers and swimmers, while the Guadalupe is more choppy and rapid and is favored by canoeists. The Comal is one of the largest springs in Texas with 8 million gallons of water flowing through every hour. The water is pure, clear and cold, about 23-29 Celsius.

Source: ©1998-2008. Texas Escapes

By now we were ready for some supper and BBQ was the order of the day. New Braunfels now has a Cooper's BBQ. The original location is in Llano, Texas, about 100 miles to the north.

Geary was unsure of the exact location of the place so, through a miracle of modern technology, he called Sue, who was in Montana. Sue put us on the right track and we were soon in the feed line.

Get it while it's hot! Whole chickens, sausage, brisket, pork chops and more. A genuine meat feast!

Never having been to a place like this I asked Geary to order for us. We ended up with over a half pound of brisket and a pound and half of pork chops.

After the meat was selected, and the portions cut, it was sent up the line to be cut smaller for easier handling, weighed, and then wrapped in butcher paper.

No plates here - or at most real BBQ joints. Beans and other fixin's came with the meal. The potato salad was a side order.

Nothing fancy here and the place clearly shows it's new-ness - a liability for a BBQ joint.

Getting down to business! The jar is full of " Cajun Chef" jalapeno peppers.

Both the brisket and the chops were delicious. Moist, tender and very flavorful.

Geary takes a few more stabs at the last morsel of pork chop. Between the two of us we had a pound of meat each, and all the beans we could eat.

Yet another Coooper's BBQ joint!

When I visited Bill and Mary in Raleigh NC they took me here for lunch. This is not like Texas BBQ, it is sauced. Some people are picky. I like 'em both!

A parting shot of the Cooper's BBQ in New Braunfels before we headed back down the road to San Antonio. A very full and fun day. Thanks Geary!!

Day 8 - FINIS