Poking Around in Pennsylvania

Huntingdon County

Thousand Steps

by Craig Mains

Poking Around in Pennsylvania

Huntingdon County

Thousand Steps

by Craig Mains

In 2020 and 2021 when Chain-Wen was working at the hospital in Bedford and I was her driver, I would drop her off at work each day. Depending on the weather, I would usually spend the day hiking around until it was time to pick her up at the end of the day. Chain told me one of her co-workers had grown up locally and liked to hike so I had Chain ask her to make a list of her favorite hikes in the Bedford area. Some of them I had already found on my own and some of them weren't on my radar, including one called the Thousand Steps trail.

I never made it to the Thousand Steps in 2020 or 2021. It was about 55 miles from Bedford in Huntingdon County and I found plenty of places to hike that were closer. When Chain returned to Bedford in 2023 though, I decided to make a day trip to the Thousand Steps trail.

The trail gets its name from this. The whole hike is mostly all stone steps with some occasional short breaks.

The trail is located along US Route 22 in Jack's Narrows, a deep gap in Jack's Mountain between Mt. Union and Mapleton. This view was looking west into part of the narrows at about step number 300. No, I wasn't counting.

Someone had thoughtfully marked the step numbers every one-hundred steps so you had some idea of your progress. There are slightly more than 1000 steps; 1043 steps gets you to a trail that runs horizontally (more or less) along the side of the mountain. According to All Trails, a hiker at this point has climbed 843 vertical feet since the trailhead in just three quarters of a mile.

Local fitness enthusiasts use the steps as a workout. I talked to two guys who ran the steps regularly. One of them said he did it almost daily if they weren't icy. He said last winter was so mild he ran them all winter. The other guy, who ran up and down the steps and part way back up again while I was there, said he ran them two or three times a week.

There were numerous bouldery scree slopes along the trail and they had a lot to do with why the steps came to be where they are. The Thousand Steps are a relic of a local industry that has come and gone. The ancient formation of the narrows exposed a lot of Tuscarora Sandstone that was useful as ganister rock. Ganister rock is a fine-grained quartz sandstone with a high silica content that is useful in the manufacturing of heat-resistant bricks. The sandstone was quarried from the side of Jack's Mountain and transported down the mountain to the town of Mt. Union where there were three large brickyards or refractory plants that exclusively produced silica bricks for industrial uses.

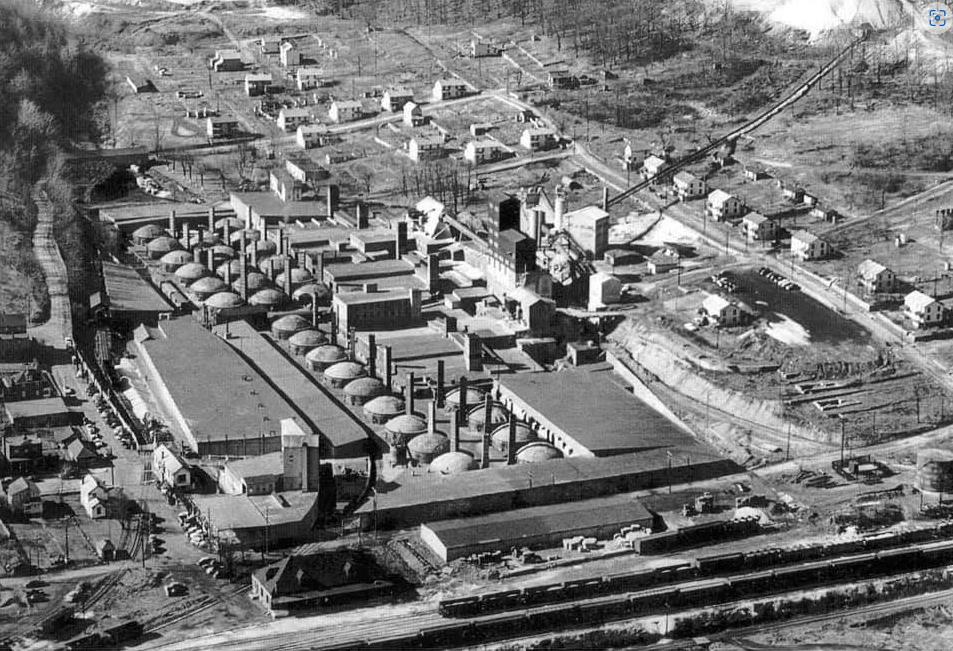

Photo: Standing Stone Trail Club

Above is an image of the Harbison-Walker refractory plant in Mt. Union. Harbison-Walker owned and surface mined the Ledge Quarry not far above the top of the Thousand Steps from 1900 to 1952. They also mined other quarries in the area, including some on the other side of the narrows.

In addition to Harbison-Walker, two other companies manufactured silica bricks in Mt. Union and the small town was known for some time as the "Silica Brick Capital of the World." Two thousand people worked in the Mt. Union brickyards and at one time half a million heat-resistant bricks were produced every day. The bricks were necessary for the steel, iron, glass, railroad, coking, and other industries.

Just beyond the top of the Thousand Stairs are the remains of this building known as the Dinky Shed.

Photo: Standing Stone Trail Club

Dinky engines were small locomotives that were used to move cars carrying the quarried ganister rock on narrow gauge tracks. This photo shows some of the early dinky engines and some of the rail cars.

Photo: Standing Stone Trail Club

A later generation Dinky engine with loaded cars.

A view of the interior of the dinky repair shed. The area in the middle was once a pit that allowed the underside of the dinkies to be serviced.

It might seem odd that a repair/maintenance shed was on the top of the mountain instead of at the Mt. Union facility. However, it seems possible that some of the company's dinkies rarely left the mountaintop. Besides the dinkies, Harbison-Walker used at least six inclined planes where the railcars carrying stone were lowered by cable to the bottom of the mountain with the empty cars then towed back up by cable. It seems possible that a dinky engine at the top transported rail cars from the quarry face to the top of the inclines and a second dinky at the bottom towed the rail cars from the bottom of the mountain across the Juniata River to the refractory plant.

The Thousand Steps were built in the aftermath of the St. Patrick's Day Flood of 1936, which ravaged a large swath of the mid-Atlantic area. It swept away part of the bridge that carried the dinky railway across the Juniata River to Mt. Union. Prior to the flood, workers traveled to the quarry face by riding the rail cars, towed either by dinky or by the cable inclines. With the bridge washed out, Harbison-Walker quarry workers were assigned to build the steps up the mountainside as an alternative route to work. Some people think that this might have been a way to keep the quarry workers busy and on the payroll during a time when the brickyard was idled.

It is not clear how often or for what length of time the quarry workers used the steps to get to work. It would have been a grueling workday to climb the steps carrying work tools (which included a 16-pound sledgehammer), bust rocks into smaller pieces, load them into the rail cars, and then walk back down the steps at the end of the day. Quarry workers were expected to load at least six tons of rock per day.

This trail near the top leads to the face of the Ledge Quarry. It was likely the former bed of a dinky rail line. I could see that a good-sized chunk of the mountain had been removed although the scar was softened by gravity, weathering, and revegetation. There were numerous scree slopes along the trail and it was hard to tell which ones were artifacts of past quarrying and which were natural. Much of the area around the old quarry had grown back up in scrubby jack pine.

One of the rewards for the hike up the stairs was this view to the west end of the narrows. In the distance is the small town of Mapleton, Pa. The highway on the right is US Route 22. On the south side of the Juniata River, what was once the main line of the Pennsylvania Railroad takes advantage of the gap in the ridge. The rail line, which is still busy, is now part of the Norfolk Southern Railroad. The Pennsylvania Canal was also once routed through the narrows.

I think it may have taken me longer to hike down the steps than it took to hike up them. While it took less exertion going down, I found it easier to find my footing going up.

The Thousand Steps trail and about 700 surrounding acres today are part of the Pennsylvania State Game Lands and are managed by the Game Commission. The trail is a segment of the 85-mile long Standing Stone Trail.

On the way back to Bedford I stopped and walked around for a bit in Mt. Union, where the brickyards once operated. This view is looking west towards the east end of the narrows. The rails are an old siding branching off from the main railroad line. They don't appear to have been in use for quite some time.

Mt. Union was well situated for the production of silica bricks. Besides the nearby ganister rock quarries, there were also nearby deposits of fire clay, as well as coal to fire the brick kilns. The railroad provided a direct link to the extensive cluster of steel, iron, glass, and coking operations in western Pennsylvania that were the market for many of the bricks.

A view of the Peduzzi Building, home to the former Peduzzi's lunch counter and soda fountain. It hasn't been in business for some time. However, it probably doesn't look much different from what it looked like 60 or 70 years ago when the brickyards were still bustling with activity.

The former Kenmar Hotel. It looks to have been split into apartments. The population of Mt. Union peaked in 1930 at 4892 people. The 2020 census counted 2308 people.

There are at least two arched, cut-stone underpasses in Mt. Union. The Pennsylvania Railroad was known for building these types of cut-stone bridges, many of which were built by immigrant Italian stone masons. There is also a six-arch, cut-stone bridge just east of Mt. Union that carries what is now the Norfolk Southern Railroad over the Juniata River.

The silica brick refractory plants were busy in Mt. Union from 1899 to about 1972. When the steel, iron, glass, and coking industries began to decline, so did the silica brick industry. There was some dwindling production of fire bricks until the early 1990s. Today, although Harbison-Walker still exists, there is little evidence of the former industry in Mt. Union.

October 2023

Sources:

Mt. Union, Pa. Wikipedia

Standing Stone Trail Club

Thousand Steps Trail - All Trails

Thousand Steps trailhead kiosk information