Poking Around in Morgantown - January 2023

Burying Raven Rock

Monongalia County

West Virginia

Poking Around in Morgantown, Burying Raven Rock

Craig Mains, January 2023

When it comes to reshaping the land surface in the Morgantown area, no human activity has had a bigger effect than building the interstate highways (with, arguably, the possible exception of surface mining.) The cut-and-fill technique of road building tranferred huge amounts of material from the sides of hills to fill in low spots. Because four-lane highways with a median strip take up a lot of space it was almost inevitable that some natural features would be damaged for the sake of progress. One of the natural landmarks lost in the Morgantown area was the now largely forgotten rock outcrop called Raven Rock.

Most people in the Morgantown area when they think of Raven Rock or Ravens Rock think of the flat-topped rock overlooking the Cheat River in Coopers Rock State Forest. However, there was (and still is, sort of) another Raven Rock near Uffington.

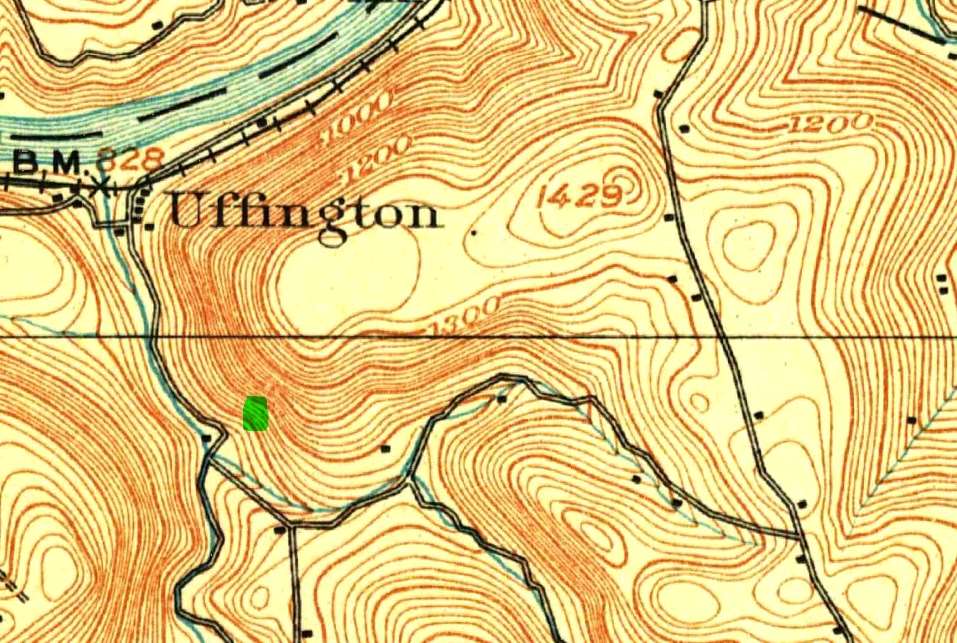

The green square on the 1902 USGS topo map of Morgantown above shows the approximate location of Raven Rock. At the time, a narrow road ran by the base of the cliff. At the turn of the century, the Raven Rock near Uffington would have been more accessible to visit than the Raven Rock near Coopers Rock. A trip to the Coopers Rock area during the horse and buggy era would have been a quite an outing, while Uffington was only about four miles from Morgantown.

The road shown on the map running roughly north-south on the right side of the image is the Grafton Road. The relatively flat-topped hill in the middle is where Scott Avenue is today

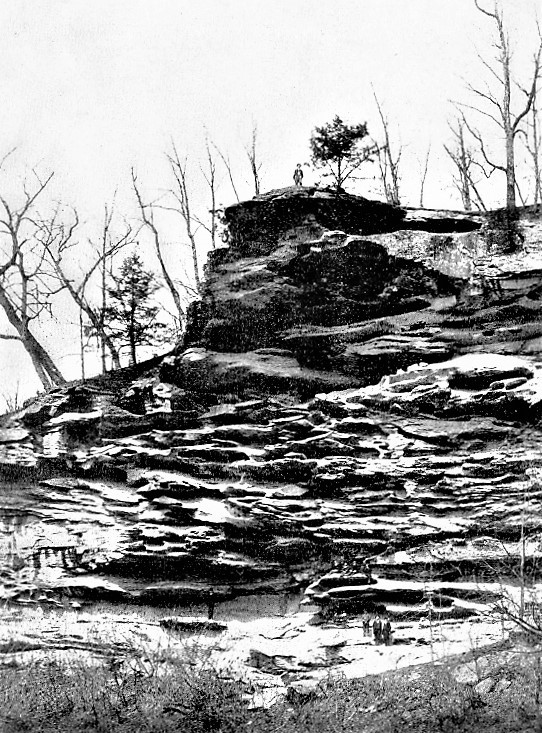

A partial view of Raven Rock near Uffington showing the numerous shelves and cavities in the face of the rock, which were believed to be the result of wind erosion. Notice the people near the bottom of the photo, who provide a sense of scale. The photo is from 1911-1912.

John L. Tilton, a professor of Geology at WVU wrote about the formation of Raven Rock in the August 1928 Proceedings of the West Virginia Academy of Science and had this to say.

At Raven Rock near Uffington is a superb illustration of present wind action in the processes of weathering. . . . the entire upper part of the cliff is seen honey-combed by wind action. Numerous cracks have received deposits from solutions, which deposits are now more resistant to weathering than the original beds. These deposits in the cracks stand out prominently, while between the ridges the softer rock is worn away.

In numerous places eddying winds blow off the loosened material and whirl it around, enlarging the cavities, so that the "box work" is varied by these numerous rounded cavities both large and small. In places the evaporation of water at the face of the cliff has so cemented the outermost portion that it has remained intact, hanging as a veil, while behind it the less cemented sand has been blown away. During strong gusts of wind these various cavities resound in a weird sort of way, emitting most startling noises.Source: John L. Tilton

This photo, which appeared in the 1913 County Geological Report for Monongalia, Marion, and Taylor Counties shows the entire vertical exposure of the outcrop. The caption in the report reads: "Raven Rocks at Uffington, Monongalia County. Here the Buffalo and Mahoning Sandstones have coalesced into a massive cliff 65 feet thick."

It is possible that this photo was taken at the same time as the previous photo. However, I've been told that Raven Rock was once a common destination for WVU geology class field trips. So, it is also possible that it was a separate outing. Besides the wind-eroded cavities there was also a lot of other geology to look at. According to Tilton there were multiple strata exposed including a white-colored sandstone towards the bottom that was in places horizontally bedded and in others cross-bedded, other horizontal beds with "small but conspicuous concretions of hematite," plus multiple small thin seams of coal up to five or six inches in thickness.

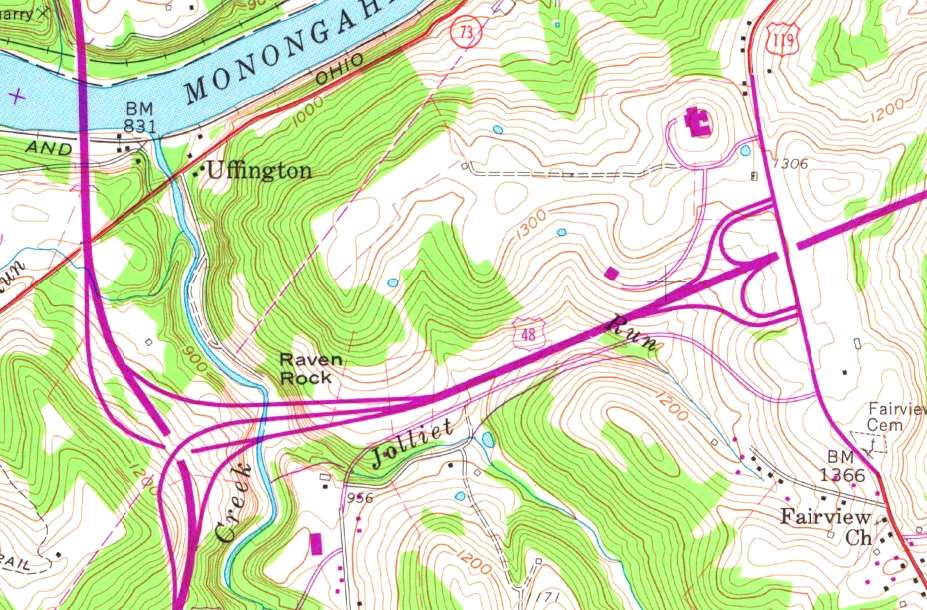

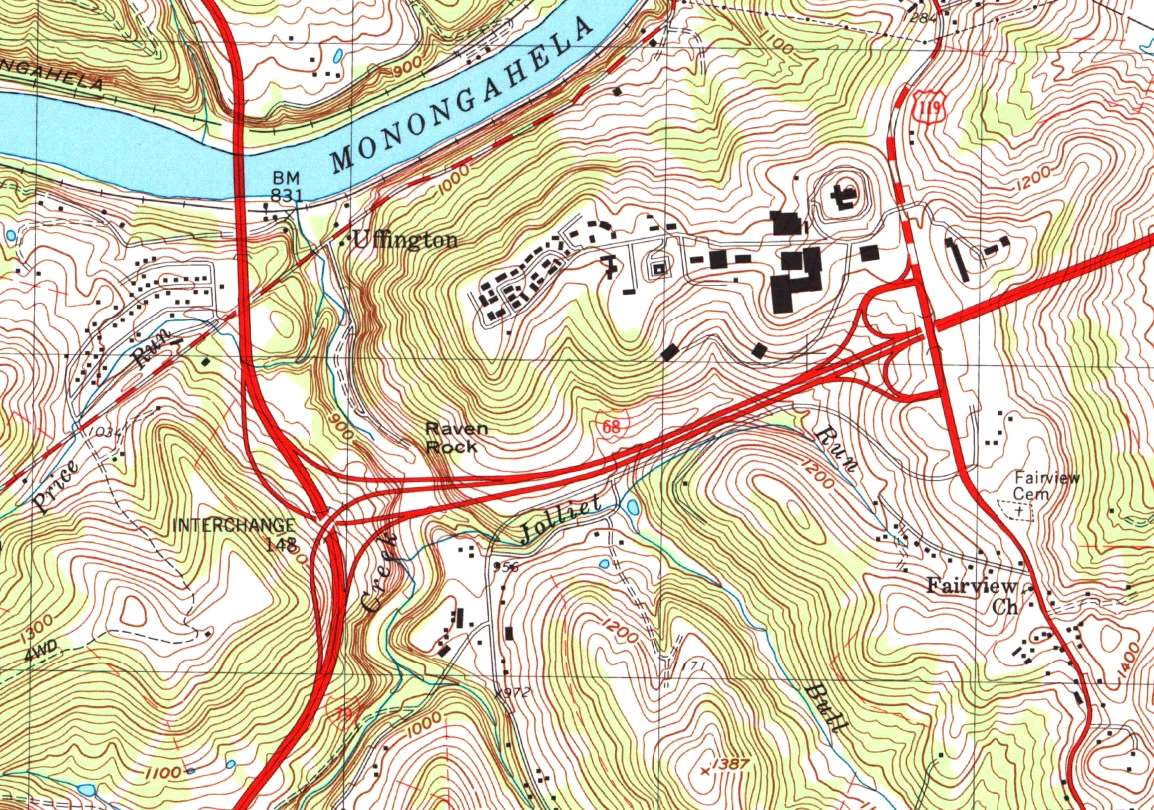

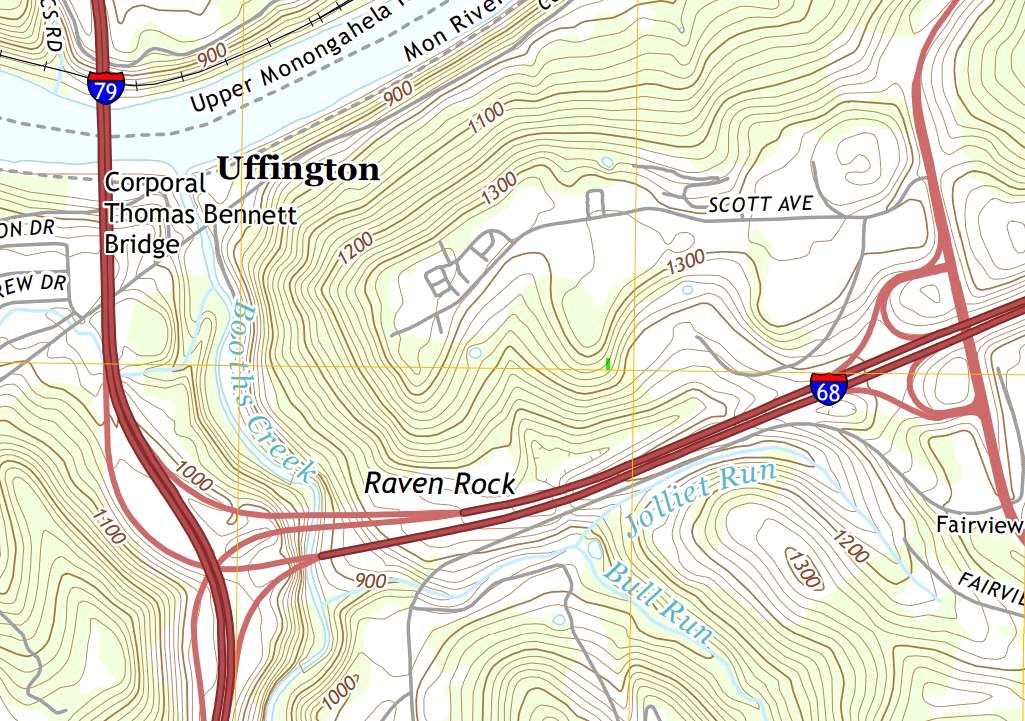

This section of the 1976 USGS Morgantown South topo map shows the addition of the interstate highways. Along the left side of the image running vertically is I-79. Running diagonally across the center is what is now I-68, which at the time was US 48. What is not shown is how the construction of the interstates modified the topography of the area, especially in the bottom left of the image where I-68 ends and merges with I-79.

As part of the construction of the interchange, a tunnel was constructed over about a one-third-mile section of Booths Creek and a massive amount of fill was added to level the area where the interchange was built. The fill extended to the face of Raven Rock, covering about two-thirds of the outcrop.

The 1976 USGS topo map shown above was a photo-revision of the 1957 Morgantown South map. Changes since 1957 were layered on in a magenta color. There is no indication of the change in topography due to the construction of the interchange.

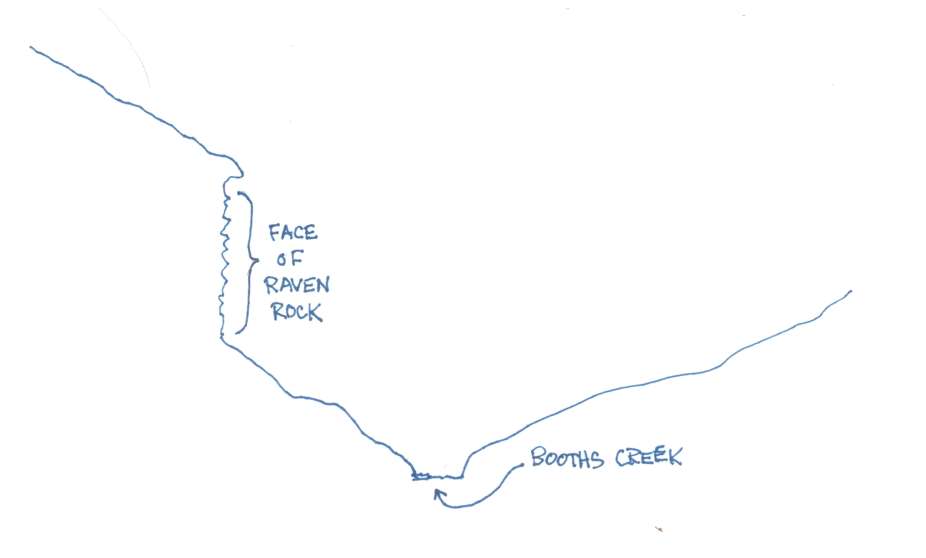

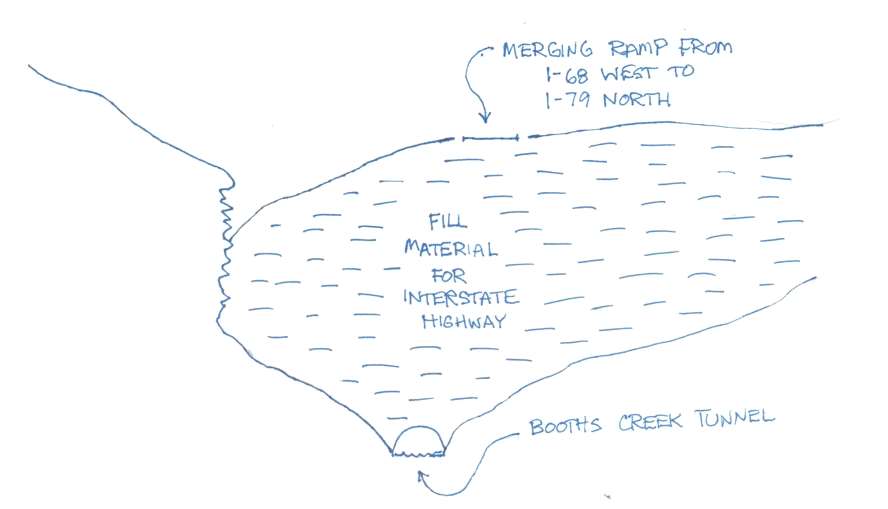

Shown above is a rough sketch of a cross-section of the Booths Creek valley prior to construction of the interstate in a roughly east (left) to west (right) direction.

Shown above is a rough sketch of the same cross-section after the construction of the Booths Creek tunnel and the construction of the the interstate interchange, illustrating that more than half of Raven Rock is now buried. Not shown on the sketch are the lanes of I-79 and the exit ramp from I-79 South to I-68 East. These would be to the west (right) of the merging ramp shown on the sketch. The drawing is not accurately to scale and is for illustrative purposes only. At its deepest point there is probably more than 100 vertical feet of fill above Booths Creek.

Note how in the original topograpy the surface at the base of the cliff sloped away, but after construction of the interstate the surface slopes towards the face of the cliff.

Raven Rock today. If you take the I-68 west ramp onto I-79 heading north it is possible to catch a glimpse of the very top of Raven Rock, especially in the winter when there is less leaf cover.

Shown above is the downstream opening of the Booths Creek tunnel. The construction of the tunnel made it possible to fill in a section of the Booths Creek valley, burying most of Raven Rock in the process

Although I estimate that about two-thirds of the face of the cliff is now buried with fill, some of the honey-combed cavities are still visible. These rocks, which are now at the bottom of the remaining exposed outcrop, were once near the top.

A closer view of one of the cavities. This is about three to four feet across.

There is a change of slope in the bank that slopes towards the face of the outcrop. While the hill that slopes from the interstate down towards the cliff is fairly steep, it abruptly gets much steeper near the face of the cliff. This means one has to scramble down into something of a narrow crevice to view the remaining cliff exposure.

Looking upward at some of the honey-combed cavities. It was believed that ravens used to nest among the cavities and ledges. There is a noticeable overhang so once one gets down into the crevice, a lot of the rock is overhead.

This view is looking straight up at part of the bottom side of the overhang. The horizontal distance from the top to the bottom of the photo is very roughly about 12 feet. The vertical distance from the ground up to this rock ceiling was probably about 15 feet.

This photo shows the steepness of the slope up against the face of the cliff and the crevice-like conditions. The slope was not quite as steep further uphill, but still fairly steep. The slope directly above the crevice is thickly vegetated with brush, preventing one from getting a full, straight-on view of the remaining exposed rocks. That makes it difficult to compare what is still exposed with older photos to make an accurate estimate of how much has been covered.

My estimate is that about 20 vertical feet of the cliff is still visible. Since the original height of Raven Rock was 65 feet, more than two-thirds has been buried.

Shown above is a segment of the 1991 USGS Morgantown South topo quad. Notice there is a gap in Booths Creek as it flows from south to the north under the interstate interchange. This represents the location of the Booths Creek tunnel. However, the contour lines have not been updated to reflect the alteration of the topography that occurred during construction of the interstate. To someone who was unfamiliar with the present topography it would appear as if the highway was somehow elevated above the original topography.

Shown above is a similar section of the 2019 USGS Morgantown South topo quad. Note that there is no longer a gap showing in Booths Creek. Perhaps the USGS felt the gap was confusing. Although there are some alterations in the elevation lines west of Booths Creek, the lines elsewhere still do not reflect the present topography of the area, even though it has been more than 50 years since the interchange was built.

Besides tunnelizing Booths Creek, and burying most of Raven Rock, "Jolliet" Run [1] was also altered during construction of I-68. The segment upstream of its confluence with Bull Run previously flowed to the north of what is now I-68. It was rerouted to flow on the south side. It was further altered when the Grafton Road Walmart Plaza was built.

A view of the I-68 and I-79 interchange, looking roughly west. The remnants of Raven Rock are to the right of the lanes that lead to I-79 north, not far beyond the grassy area. In the distance you can see how the embankment slopes steeply downwards toward the face of Raven Rock. The grassy area in the foreground is fill as well.

Although what remains of Raven Rock appears to be within the right-of-way of the interstate, and therefore on public land, it is not an easy location to access. Pedestrians are technically prohibited along the interstate and getting to Raven Rock involves bushwacking through thick brush, including multiflora rose, and navigating some steep slopes. The easiest way to access Raven Rock would be to approach it from Uffington, following Booths Creek upstream. However, the property one would have to cross coming from Uffington is leased by a hunting club, is heavily posted with No Trespassing signs, and is under video surveillance.

Footnotes

[1] Jolliet

Some time in the 1970s I remember hearing a local person refer to the stream that is labeled on maps as "Jolliet" Run as "Jolliffe" Run. I didn't think too much about it at the time. However, sometime later while viewing the 1886 D.L. Lake Co. map of Marion and Monongalia Counties, which shows the names of local landowners, I noticed that there were then quite a few Jolliffes living in the Clinton District. Since many local streams are named after early settlers that led me to think that Jolliet Run may have been a spelling error, first appearing on the 1925 USGS map and then carried onto subsequent versions.

Back to Main Text

References

Clinton Magisterial District, Uffington P.O., Smithtown, Clinton Furnace P.O., Halleck P.O. Map. D.L Lake Co., Atlas of Marion and Monongalia Counties. 1886.

Source: https://www.historicmapworks.com/Dadisman, A.J. "People at Raven's Rock, Uffington, W.Va." Photograph. 1911/1912. West Virginia History OnView, WVU Libraries.

Source: wvhistoryonview.org.Hennen, Ray V. and Reger, David B. "Marion, Monongalia, and Taylor Counties." Raven Rocks, Photograph, Plate XX. West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey. 1913.

Source: https://archive.org/Tilton, John L. "Two Illustrations of Wind Action in West Virginia." Proceedings of West Virginia Academy of Science. West Virginia University Bulletin. Vol. 2, August 28, pp.145-150.

Source: https://pwvas.org/.United State Geological Survey. "Morgantown, WV." USGS, 1902. Map.

Source: USGS Topo View.United State Geological Survey. "Morgantown South, WV." USGS, 1976. Map.

Source: USGS Topo View.United State Geological Survey. "Morgantown South, WV." USGS, 1991. Map.

Source: USGS Topo View.United State Geological Survey. "Morgantown South, WV." USGS, 2019. Map.

Source: USGS Topo View.

In Memoriam

John Littleton Tilton

Prof. John L. Tilton, one of our Academy's long-time fellows, passed from amidst us a few weeks ago, stricken with a heart attack, coronary thrombosis the doctors pronounced it, while delivering a lecture before his class in geology in the West Virginia University. For more than 30 years Doctor Tilton was one of our most active members in the Academy, almost always present at our annual gatherings, always taking enthusiastic part in our proceedings, and usually reading one or more papers at each session. A decade ago his removal from our state to West Virginia closed also his active participation in our Academy's annual meetings

Doctor Tilton was born at Nashua, New Hampshire, on January 11, 1863; and died at Morgantown, West Virginia, on November 17, 1930'. He was therefore 66 years of age at the time of his demise. He attended Wesleyan University, at Middletown, Connecticut, from which he was graduated in 1885, with the degree of A.B. After a year's teaching in the Niantic public schools, he returned to Wesleyan, and after remaining two years proceeded to his Master's degree. Harvard University also conferred the A.M. degree upon him in 1895; and he took his doctorate at the University of Chicago in 1910.

After his two years' sojourn at Wesleyan University he was called to Simpson College, at Indianola, where he held the chair .of geology and physics for 32 years. For the last ten years of his life he occupied the chair of geology at West Virginia University.

Doctor Tilton was before all an inspiring teacher, and his life was devoted to college work. However, he was deeply interested in many things besides education; and he accomplished not a little research work, most of which was undertaken chief:ly in connection with the geological surveys of Iowa and West Virginia. While associated with these organizations he prepared and published a number of important reports on the geology of these states, including altogether a dozen or more counties, besides a large number of less pretentious papers on special topics which presented themselves in the course of his other investigations.

Altogether 23 papers were read before our Academy; while half a hundred titles are accredited to him. A bibliography of his Iowa contributions. to the year 1913 appears in volume XXII of the Iowa Geological Survey.

Doctor Tilton was honored by his confreres with membership in manye ducational, social, and scientific societies, including, amongst the last mentioned, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the Geological Society of America, the Paleontological Society of America, the Iowa Academy of Science, and the West Yirginia Academy of Science.

Source: Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science, Vol. 38 [1931], No. 1, Art. 5