Poking Around in Portage

Wisconsin

August 2019

by Craig Mains

Poking Around in Portage

by Craig Mains

In 2019 Chain-Wen was intermittently working at a hospital in Portage, Wisconsin. Most of the time she went back and forth on her own but I spent one week there with her in early July. That gave me some time to walk around in Portage during the day while she was at work.

For a small town in the upper midwest (population about 10,600), Portage has a deep history. The red dot on the map above shows the location of Portage. For more than 200 years until the mid 1800s, Portage was an important place because of two things---its unique location and beaver hats. Notice on the map that the headwaters of the Fox River flow close to the Wisconsin River. The land between the two rivers is relatively flat, which allowed for a short portage between two major North American watersheds. The Wisconsin River is a tributary to the Mississippi River and the Fox River is a tributary to Lake Michigan and the Great Lakes/St. Lawrence River.

This was important because beaver hats, which had long been fashionable in Europe and later in the American colonies, had led to the near extirpation of European beavers. And, by the 1600s, beavers were becoming scarce in eastern North America. By providing a link between the Mississippi drainage and the Great Lakes, it helped open up much of the west to the fur trade. Many tons of beaver pelts and other furs were portaged in the area that later became the town of Portage. [1]

Native Americans had been using the portage for millenia. The first mention of the portage by Europeans was in 1634 when French explorer Jean Nicolet canoed up the Fox River. He traveled as far up the Fox as a Mascouten Indian village, where he was told of the portage, although he did not reach it himself. The first documented white men to use the portage were Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet who were sent to spread Christianity and find a passage to the Pacific Ocean. They didn't find the latter but they verified the location of the Mississippi River and traveled on far enough to confirm that the Mississippi headed towards the Gulf of Mexico. In 1683, Charles Pierre Le Sueur traveled on the Fox and Wisconsin Rivers, contributing to opening up the Mississippi to trading.

Although there were a number of other portages between the Mississippi River and the Great Lakes, both north and south, the Fox/Wisconsin portage was considered one of the best because canoes only had to be carried a about a mile and a half and the topography was relatively level, although marshy. [2]

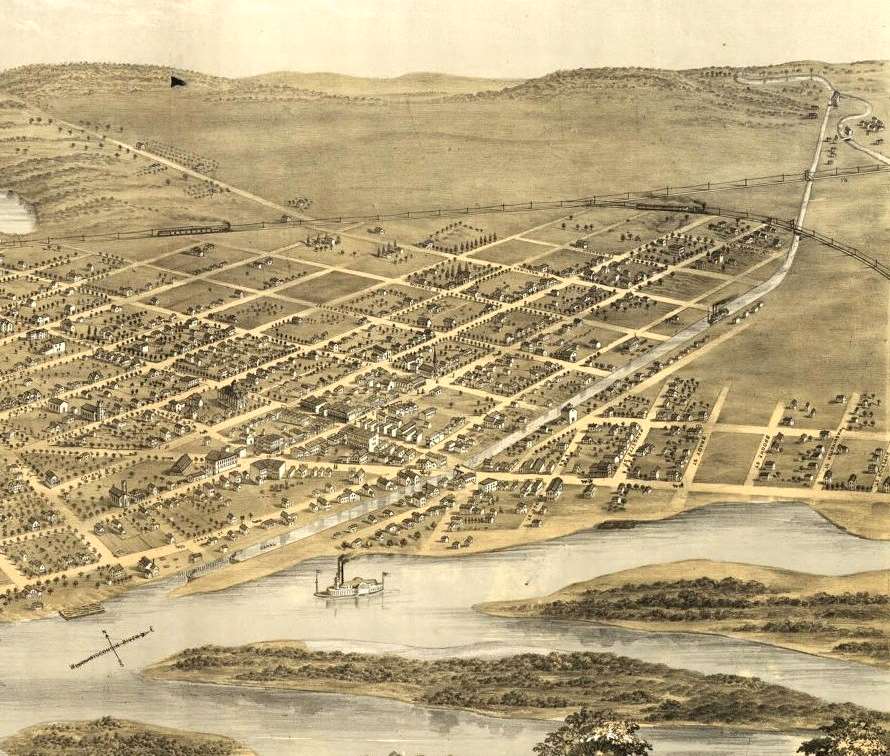

Shown above is a section of an 1868 Bird's Eye View Map of Portage. The Wisconsin River runs across the bottom of the picture. The headwaters of the Fox River are shown in the upper right corner of the image. The map shows a navigable canal that has replaced the portage. The canal stretches from the lower left of the image to the upper right.

Starting in the late 1830s through the 1850s there were multiple attempts to build a canal between the two rivers. By 1851 it was possible to ship bulk commodities such as lumber and grain between Portage and the cities on the lower Fox River.

Note the presence of the railroad in the background. Rail lines for the Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul Railroad were completed through Portage in the late 1850s. It didn't take long for the railroad to replace riverboats for moving bulk goods between cities. The seeds of the canal's obsolescence were planted not long after the first set of canal locks was completed.

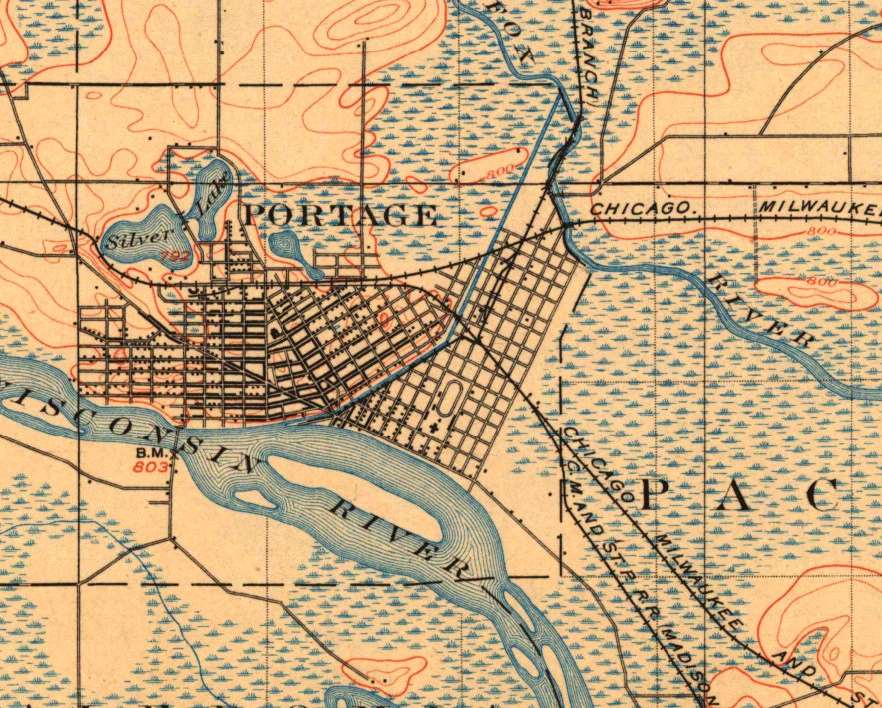

Shown above is a section of the 1902 US Geological Survey map of Portage. It shows that Portage is surrounded by a patchwork of wetlands (the blue stippled areas) and slightly higher areas. The higher areas are a mix of prairies and oak forests. The wetlands limited the direction that Portage could expand into. Most of the growth of the city since this map was made has occurred on the higher ground north and west of Silver Lake.

The following photos are taken from the daily walks I took in and around Portage.

Shown above is a view of the Wisconsin River. It is known for having numerous sand bars and islands due to the river flowing through debris left behind by glaciers. The distance from Portage downstream to the Mississippi River is about 116 miles. The river falls about 171 feet over that distance at a fairly uniform gradient.

Portage has about a three-mile levee along the Wisconsin River, which makes for a nice walk with good views of the river. Although the city is on slightly higher ground, it was subject to flooding in the past and still would be without the levee

A view of the gates of the Portage lock on the southwest end of the canal. It is no longer functional.

By 1820, boats and goods were no longer being carried by manpower across the portage. A road had been built and boats and goods were transported on ox-carts. By the 1830s, efforts were made to built a canal between the rivers. Locks were completed on the Portage Canal by 1851. However, it wasn't until 1856 that the entire Fox/Wisconsin waterway was fully navigable end to end, and, by then, the emergence of the railroads meant that soon the canal was no longer that crucial. By the turn of the century the canal was used mainly by pleasure boaters. In 1951 the Army Corps of Engineers closed the canal by welding the southwest gate closed and bulldozing in the northeast gate.

Although the Fox-Wisconsin waterway played a major role in the days when furs and other goods were moved by canoes and French-Canadian bateaux, its importance declined over time. The main reasons were the superior reliability of the railroads and the completion of a better canal between Lake Michigan and the Mississippi at Chicago. Even after completion of locks from end to end, the Fox-Wisconsin waterway was limited by low flows on the upper Fox and shifting sands on the Lower Wisconsin.

A view of the canal near the Fox River end of the canal.

A view of the Fox River near Portage. Because the Fox River in the vicinity of the portage was near the headwaters of the river, it was not as big as the Wisconsin River, which was a limitation on the size of boats that could travel on it. Early on, it was known for being a very meandering stream. One early traveler in the area noted that he had canoed for hours and could still see his point of departure. Even after dredging and straightening, the upper Fox was still not suitable for bigger steamboats. From Portage to the mouth of the Fox River at Green Bay is about 162 river miles. [3]

It was somewhere near here that I almost stepped on a wild turkey. There was supposedly a trail along the river but it was unmarked, faint, and was grown up in waist-high grass in which a turkey was well hidden. He didn't take flight until I was almost upon him. One more step and I would have stepped on him (or her). I was startled to say the least by what momentarily seemed like a small explosion.

Shown above is what is known as the Old Indian Agency House, built in 1832. The main tribe living in the Portage area at the time it was built were the Ho-Chunk, also known as the Winnebago. As more settlers arrived in Wisconsin, the federal government pressured the Ho-Chunk to give up some of their territory. Settlers started to pour into Ho-Chunk land before negotiations were completed, angering some of the Ho-Chunk and resulting in some attacks on the settlers in 1827.

In response, the US built Fort Winnebago on the Fox River near the north end of the portage in 1828 to pacify the Ho-Chunk and to ensure that the portage wasn't blocked. In 1832 the Indian Agency House was built on the opposite side of the Fox River from the fort and was intended to serve as a sort of embassy for the US government to the Ho-Chunk. The building housed the Indian sub-agent and his family. The main duties of the sub-agent were to mediate disputes and to distribute the annual annuity to the Ho-Chunk that was one of the conditions of the treaty in which they gave up territory. Fort Winnebago was abandoned in 1845 and most of the buildings burned in 1857. The Indian Agency House was staffed only until 1837. Presumeably this was because with the passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830, which had the goal of moving all Indians east of the Mississippi to federally owned land in the west, the facility was probably thought to be unnecessary. However, the Ho-Chunk semi-successfully resisted removal and there are still Ho-Chunk Indians in Wisconsin. [4]

The Indian Agency House has been operated as a non-profit museum by the Colonial Dames of America since 1932. I had a pleasant conversation with one of the Colonial Dames, who was working in the garden outside. She clued me in to a nice loop trail of about two miles on the property

During our conversation, the Colonial Dame mentioned that noted conservationist Aldo Leopold had evaluated some of the land around the Indian Agency House and had noted the presence of many native prairie species. He thought the open areas were good candidates for tallgrass prairie restoration, although it doesn't seem like any restoration project was ever initiated. After working for the US Forest Service, Leopold was a professor of wildlife management at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. His 1949 book, A Sand County Almanac, was based on his observations at his rural family home in Sauk County, which is one county to the west of Portage.

She also mentioned that naturalist, botanist, writer, and advocate for wilderness preservation, John Muir, spent part of his childhood on a farm just outside of Portage. His family moved to Wisconsin from Scotland when Muir was 11. Leopold's and Muir's writings were both influential in the emergence of the American conservationist/environmental movement and, although they were born elsewhere, both had some roots in the Portage area.

Another view from the loop trail showing the mixture of forest and openings that were present in the more upland areas. The natural vegetation of southern Wisconsin represents a transition between the well-watered eastern forests and the dryer prairies to the west.

Another view of the savanna-like vegetation on the upland area on the loop trail.

One of my other walks took me into the lower-lying areas outside of Portage. This standing-water wetland was along Ontario Avenue.

After it crossed the railroad tracks Ontario Avenue turned into a dirt road that ran out into a marsh.

This area is shown on some maps as the Swan Lake State Wildlife Area. I didn't know that at the time, however. There were a couple areas that I might have explored a little more had I known it was public land.

Another view of the marsh. The original portage would have come across this general area so even though it was level it may not have been that easy. Even before a cart road was built there must have been some sort of an elevated path to keep people from sinking in while they were portaging heavy loads.

Except for an occasional red-winged blackbird, I didn't see many birds on either of my two walks in this area. However, I could really hear them chattering, hidden among the rushes.

Probably about half of my Portage perambulations were in town. Portage had some old neighborhoods and back alleys to explore. The following photos are from walking around in town.

This house appeared to be unoccupied although there was no For Sale sign.

I found the back side of these buildings more interesting than the front side.

One of the grander homes in Portage. We were there the week of the Fourth of July so some homes had patriotic bunting out.

One of the other grand houses was this one, which is now a local history museum. The house was once shared by writer, Zona Gale, and her husband, William Breese. Zona Gale (1874-1938) grew up in Portage and spent most of her adult life there. She was a novelist, short story writer, and playwright. Her writings depicted everyday life in fictional midwestern towns, of which it was widely assumed that Portage provided the inspiration. She won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1921. Although, outside of Portage, she now is largely unknown, she was popular nationally in the 1920s and her realistic portrayals of common people were compared to Theodore Dreiser and Sinclair Lewis.

At age 54 she married widower William Breese, a wealthy banker and businessman. When Gale died in 1938, Breese donated the house they had shared to the city as a memorial to her.

One of the rooms inside the museum. There were three floors of displays that were a mixture of permanent and temporary exhibits. One corner was devoted to the various Olympic gold medal winners in curling that came from Portage. There were also exhibits about the canal and old houses in Portage. The entire attic floor was a collection of old toys. I was somewhat dismayed to recognize that some of the toys I had as a kid were now old enough to be displayed in a museum.

One of the things I learned at the museum was that over the years Portage had three different brickyards and all of them made light colored bricks---either yellow or a light brown color.

I didn't notice that someone was sitting at the window when I took this picture.

It was possible to find an occasional red brick house in Portage but they were rare compared to the light-colored brick houses.

This house had been painted. It was yellow brick underneath. The three front-facing gables seemed to be something of a recurring architectural theme.

This has to be the smallest Odd Fellows lodge in the country. It wasn't much deeper than it was wide.

I was impressed with how clean and shiny these tank cars were. It was like they just came out of the factory. A man happened to be outside of one of the houses next to the tracks so I asked him if he had any idea what the cars were carrying. He told me he wasn't sure but he thought it was probably ethanol. That made sense---Wisconsin has nine plants that turn corn into ethanol. Most of the country's "bio-refineries" are concentrated in the upper midwestern corn belt.

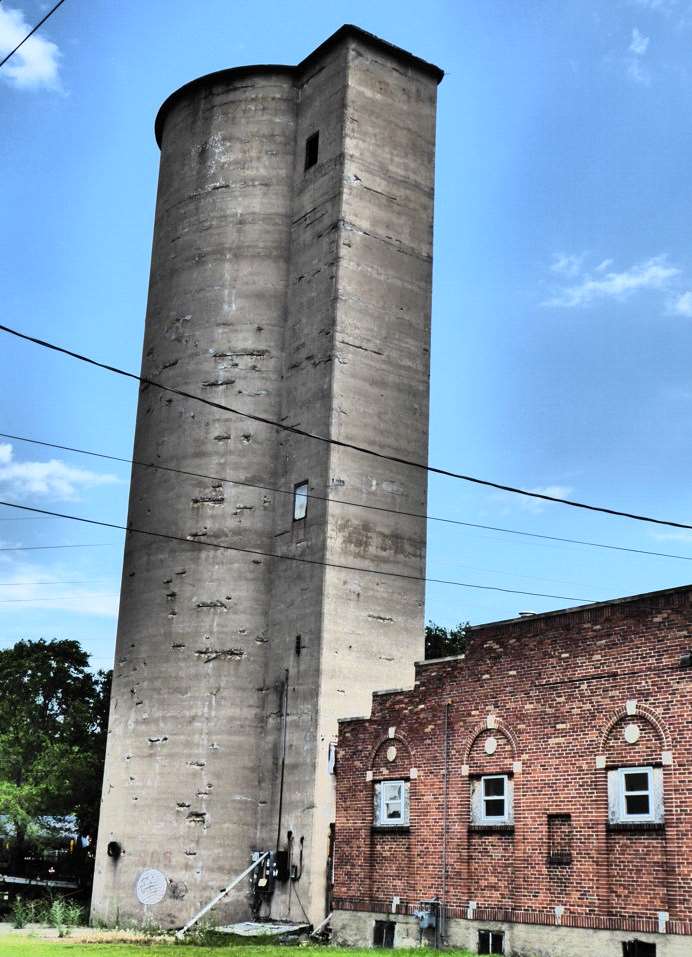

I assume these silos and the one in the previous photo were once used for storing grain. They were both located next to the rail line. It didn't appear that any of them had been used for some time.

Another house with three front-facing gables.

Jack's Tap.

Friendly Tavern. Both Jack's Tap and Friendly Tavern seemed to me to be quintessential mid-western, working-class neighborhood watering holes. Because it was July, most of my Portage walks were in the morning before it got too hot. Neither Jack's Tap nor Friendly Tavern were yet open when I wandered by. Otherwise, I might have been tempted to stop in for lunch as I ended my walks.

August 2019

Footnotes

[1]

Beaver hats were popular in Europe going back to the 1500s. Hair was shaved from the beaver pelt and processed to make it into felt, which was molded into the desired shape of the hat and then brushed to give it a sheen. Almost all types of men's hats, both civilian and military, were made of beaver. If beaver hats hadn't fallen out of style in favor of silk hats, it is possible that beavers would have eventually been trapped to extinction. Part of the process of making the felt involved the use of mercury, which caused a variety of occupational health problems including dementia and is the source of the saying, "mad as a hatter."

The fur trade, of course, wasn't limited to beavers. Fur traders would also trade for "fancy" furs like mink, marten, fox, and lynx, etc. However, beaver pelts for hats were the driving force. The demand for beaver started to decline in the 1830s.

Back to Main Text

[2]

Fur trading was a grueling occupation. With portages, every step counted. One early map of the Wisconsin/Fox portage included the notation, "2700 paces." Fur traders, of course, had to carry their canoes or bateaux across the portage. At the time the North Canoes used by fur traders were commonly up to 25 feet long and weighed about 300 pounds. (The canoes used on the Great Lakes were even bigger.) They also had to portage all of their supplies, trade goods, and whatever pelts they had gathered. The pelts were pressed into bales that had an average weight of 90 pounds. The traders commonly portaged two or more bales in one trip! They could fit between 25 to 30 bales in a canoe. The long North Canoes had a crew of four to six people so everyone typically had to make multiple trips at each portage. Fur traders rarely made enough money to escape to a different line of work and usually worked until their bodies gave out.

Back to Main Text

[3]

While the portage between the Fox and the Wisconsin was short and level, that was not the case at the lower end of the Fox River. Between Portage and Lake Winnebago, a distance of about 110 miles, the Fox River only dropped about 36 feet, an average of only four inches per mile. Between the mouth of Lake Winnebago and Lake Michigan, however, the river dropped 169 feet over a distance of 39 miles, a gradient of four feet per mile. And, at Kaukauna, the river dropped 50 feet in one mile. That made for a grueling portage in the early days and later necessitated the construction of a series of 17 locks, which, by the time they were built, were practically obsolete.

Back to Main Text

[4]

Indian removal in Wisconsin did not get as much attention as that of the southeastern tribes. It was not quite as brutal as the Trail of Tears. There were multiple removals of Ho-Chunk to western lands including in 1840, 1848, 1850, and finally in 1873. Some of the tribe ended up on a reservation in Nebraska. Others successfully resisted removal by living as fugitives in remote areas of Wisconsin, by purposefully dragging out removal negotiations as long as possible, by buying property, and by submitting to relocation to western areas but then returning to Wisconsin at the first opportunity. By the 1870s, white Wisconsinites were split on Indian removal, with both supporters and opponents. After the final removal in 1873 both the state and federal governments gave up on further removal. There are now two related but distinct Ho-Chunk tribes---the Winnebago tribe of Nebraska (population about 4000) and the Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin (with a 2011 population of about 7200, with about 5000 of those living in Wisconsin). They are spread across numerous counties in Wisconsin and some in Minnesota and Illinois.

Winnebago is a name that was given in the past to the tribe by neighboring Algonquin-speaking tribes. The Wisconsin tribe, prefers to go by Ho-Chunk, which is closer to what they referred to themselves as in their Siouan language.

Back to Main Text

Sources

McKay, Joyce. "Portage at the Fox-Wisconsin: A Sesqui-Centennial History of the Area." 2002. City of Portage and Portage Historical Society. Accessed at studylib.net.

Museum at the Portage. https://portagemuseum.org

Onsager, Lawrence W., "The Removal of the Winnebago Indians from Wisconsin in 1873-1874." 1985. Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations, & Projects. #1066. Portage Canal Association. portagecanal.org

Brittanica and Wikipedia pages for Aldo Leopold, Beaver Hats, bateaux, coureurs de bois, Fox-Wisconsin Waterway, Indian Removal, John Muir, Portage Canal, voyageurs, and Zona Gale.

"The Wisconsin River is a wide and shallow stream running over a bed of sand with transparent water and chequered with small islands and sandbars. The navigation of the river is considerably impeded by the sandbars and small islands and some time is lost searching for the proper channel." ---Henry Schoolcraft, 1820.

"A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise." ---Aldo Leopold

"If one tugs at a single thing in nature, he finds it attached to the rest of the world." ---John Muir