Great Depression

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

- This article is about the worldwide economic crisis of the 1930s; for other uses of the term, see The Great Depression (disambiguation).

The Great Depression was a massive global economic recession (or "depression") that ran from 1929 to approximately 1941. Its primary impact was in the United States of America and Germany and led therein to numerous bank failures, high unemployment, as well as dramatic drops in Gross Domestic Product (GDP), industrial production, stock market share prices and virtually every other measure of economic growth. It is generally considered to have bottomed out in 1933, but it was not until well after the end of World War II before such indicators as industrial production, share prices and global GDP surpassed their 1929 levels.

What gave this downturn the name the "Great Depression" was that it was by far the largest sustained decline in industrial production and productivity in the century and a half for which economic records have been regularly kept, and the fact that its impact was felt throughout the entire industrialized world and their trading partners in less developed nations.

The term Great Depression can refer to the economic event, but it can also refer to the cultural period, often called simply "The Depression", and to the political response to the economic events.

Contents |

Causes of the Great Depression

Main Article: Causes of the Great Depression

Economists, historians and political scientists have posed several theories for the cause, or causes, of the Great Depression. It remains one of the most studied events of economic history. Today, it is generally accepted that the Great Depression was caused by the government's mismanagement of monetary policy.

Theories from mainstream capitalist economics focus on the relationship between production, consumption and credit, as embodied in macro-economics and on personal incentives and purchasing decisions as embodied in micro-economics. In these theories attempts are made to order the sequence of events which imploded the industrialized world's monetary system and its trade relationships. Theories from Marxist economics focus on the relationships of the control of production and the concentration of wealth. For Marxists, the Great Depression is the kind of crisis to which capitalism is prone and its occurrence is not surprising.

Other heterodox theories of the Great Depression have been advanced and from time to time gain favor. These include the theory of long-cycle activity and that the Great Depression was a period at the intersection of several concurrent long cycle troughs.

More recently, it has been the prevailing belief among economists that the stock market crash of 1929 was not the primary cause of the Great Depression, pointing to telltale signs of an imminent economic disaster in various statistics leading up to the Depression as well as the downturn in Europe which was already in progress. Today the most widely accepted theory is the one advanced by Peter Temin: the Great Depression was caused by catastrophically poor monetary policy pursued by the United States Federal Reserve during the years leading to the Great Depression. The policy of contracting the money supply was an attempt to restrain inflation, which exacerbated the actual problem in the economy, which was deflation.

Responses

The Wall Street crash is widely considered to be the event which marked the start of the world-wide financial crisis. In the United States between 1929 and 1933, unemployment soared from approximately 3% to over 25%, while manufacturing output declined by one-third. Governments worldwide sought economic recovery by adopting restrictive autarkic policies such as high tariffs, import quotas and barter agreements and by experimenting with new plans for their internal economies.

Economic crises due to the depression created great problems throughout the United States and much of the world. Consumers reduced their purchases of luxury products and many businesses cut production. Big businesses, such as General Motors, saw their sales drop by 50% in the late 1920s and the early 1930s. This caused businesses to cut back on the numbers they employed, with thousands of workers losing their jobs.

When farm prices fell, small farmers went bankrupt and in the USA many lost their land due to bank foreclosure. By June of 1932 the American economy had shed about 55% of the work force. On July 8, 1932, the Dow Jones Industrial Average plunged to 41.22. The United States government responded by instituting the New Deal policy which was an attempt to restore prosperity by spending on welfare and public works.

After the stock market collapse, the New York based banks became concerned over the security of overseas loans and called in their loans to Germany and Austria. However, without the American money, Germany was unable to continue making World War One reparations payments to France and Britain. This chain reaction meant they in turn could not repay their war loans to America. Therefore, the depression had spread to Europe. All governments were forced to cease paying both reparations and war loan repayments.

The United States government tried to protect domestic industries from foreign competition by imposing the highest import duty in American history. In retaliation, other countries raised their tariffs on imports of American goods. As a result, global industrial production declined by 36% between 1929 and 1932, while world trade dropped by 62%.

In Germany unemployment increased drastically fueling widespread disillusionment and anger. The institutions of the Weimar Republic, which had already been unable to maintain order in Germany, further deteriorated in the years from 1930 to 1932, while the Chancellor and finance expert Heinrich Brüning attempted to fix the economy by drastically cutting state spending. At the time the NSDAP, or Nazi party, gained much popularity, winning the two general elections in 1932. This eventually led to the appointment of Adolf Hitler as Chancellor on January 30, 1933 (See Weimar Republic for details). In Nazi Germany, economic recovery was pursued through rearmament, conscription, and public works programs. In Benito Mussolini's Italy, the economic controls of his corporate state were tightened.

In the United Kingdom, the Labour government of Ramsay MacDonald, and later the Conservative-dominated coalition "National Government", responded to the depression by imposing tariffs on all imports from outside the British Empire (arguably worsening the global situation), by cutting public spending, and by abandoning the Gold Standard which reduced the cost of British exports (see Great Depression in the United Kingdom).

In the Netherlands some projects were started to give people employment and boost the economy, such as the Amsterdamse Bos, a reforestation project near Amsterdam. In Heerlen fabric merchant Schunck commissioned a new building in 1934 for his business, the hypermodern Glaspaleis (Crystal Palace) the tallest building in the city at the time.

In the United States, President Herbert Hoover made efforts to control the situation. However he gravely underestimated the severity of the crisis, even announcing to U.S. Congress on December 3, 1929, that the worst effects of the recent stock market crash were behind them, and that the U.S. public had regained faith in the economy. Over the following months it became apparent this was not the case, and Hoover went before Congress again on December 2, 1930 to ask for a $150 million public works program to help generate jobs. However, one of the major problems was that with deflation, the currency that you kept in your pocket could buy more goods as prices went down. Another was that there had been no federal oversight of the stock market or other investment markets, and with the collapse many stock and investment schemes were found to be either insolvent or outright frauds. Unfortunately, many banks had invested in these schemes and this may have precipitated a collapse of the banking system in 1932; Milton Friedman's monetary theories suggest that the inexperience of the newly-created Federal Reserve in managing the money supply exacerbated the problem. With the banking system in shambles, and people holding on to whatever currency that they had, there was minimal cash available for any activities that would cause positive change.

The response of the Hoover administration helped little; instead of increasing the money supply, the Hoover administration did the exact opposite and raised interest rates, falsely believing that inflation was the real danger. Many in the Hoover administration believed that as wages fell, the cost of production would drop and, as a result, production would pick up again--the depression would be self-correcting. Nobody at that time foresaw the effects of a calamitous drop in the money supply. For this reason, they saw no need for the government to intervene in the economy, a policy which proved disastrous.

Like their counterparts abroad, many Americans were disillusioned with their system of government, believing that Hoover's policies had driven the country to ruin. Shanty towns populated by unemployed people at the time were often dubbed Hoovervilles, highlighting the President's fading popularity. During this period, several alternative political movements saw a considerable increase in membership. In particular, a number of high-profile figures embraced the ideals of Communism and the Communist Party encouraged its followers to "Follow the Example of Mother Bloor", a descendent of "good Yankee stock" who embraced the movement. Radio speakers, such as Father Charles Coughlin, saw their listening audiences swell into the millions as they sought easy scapegoats for the country's woes.

Upon accepting the Democratic nomination for president (July 2, 1932), Franklin D. Roosevelt promised "a new deal for the American people", a phrase that has endured as a label for his administration and its many domestic achievements. Upon being elected in 1932 he proposed the "New Deal", a platform of government programs based on Keynesian economics and intended to stimulate and revitalize the economy. The British and French governments also intervened in their economies to escape the worst effects of the depression.

Australia and the Depression

Australia was one of the countries hardest hit by the depression; due to the dependance on Britian and the United States, and the huge War debts it still owed to these countries. The small population and reliance on international trade also caused internal problems.

Rapidly deflating prices caused farmers goods to become worthless and were sometimes burned or destroyed. In the city the situation was entirely different. Food shortages, and radical unemployment hit Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide. From 1929 to 1934 unemployment was above 25%, and in South Australia in 1931 unemployment passed 35%.

To combat this unemployment the federal government began building many public works; the most famous of these is the Sydney Harbour Bridge, which was controversially opened in 1931 by NSW Premier Jack Lang. The bridge, which spans Port Jackson, provided a vital link between the North Shore and the CBD. It remains to this day the widest bridge in the world, and an internationally recognised Sydney landmark.

In 1931, when national unemployment was at 30%, the federal government requested that state government buildings be turned into accomadation for the vast numbers of homeless people, especially in Sydney and Adelaide. Permanent campsites were set up outside Sydney.

In 1931 the NSW premier Jack Lang refused to pay back war debts owed to Britain, as the money was needed in Australia. However, Britain, in depression itself, demanded this money, and Jack Lang was sacked by the Governor General, Sir Philip Game, the British Monarchy's Representative in Australia.

Daily Life in the United States during the Depression

Contrary to popular belief, the Stock Market Crash and Great Depression did not plunge all Americans into instant poverty. While the full effects of the Depression were imminent, they were not universally immediate. Indeed, following the October event on Wall Street, economists who underestimated the event felt that the crash of the market was simply a long over due, albeit major, market correction.

However when the market failed to rebound, and it became apparent that even highly regarded consumer goods manufacturers were in trouble (example, Atwater-Kent Radios, Willys-Overland, etc.) the effects began to impact economy. Not only did name-brand product manufacturers fail, but their suppliers and retailers also failed.

Easy credit fuelled the consumer driven economy of the 1920s, and following the depression, credit availability began to tighten, both for business and consumers. With lenders restricting their credit availability, and moving quickly to secure their liabilities, employers who were hurt by the ripple effect of Wall Street were the first to be liquidated. As employers closed their companies, the ranks of the unemployed grew, which further complicated the banking situation by reducing income from credit lines, which cascaded into a liquidity crisis leading up to the banking panic of 1933.

Consumers who had taken advantage of “easy term” payments offered by retailers found themselves backed against the wall if they were unable to meet those obligations. The repossession of furniture and household goods by creditors – something that had before only happened to a limited number of households became a commonplace event.

Foreclosures on the American home – often seen as the safest investment that one could make – rose throughout the period, and affected people in all income brackets. Prior to the depression, foreclosure and eviction had been a mantle of shame, and closely viewed as caused by personal failure. However as the effects of the Depression dug deeper into the fabric of the nation, average Americans changed their view of foreclosure making it not a mark of shame, but as a battle of the common man against the banking industry. In the upper Midwest, the posting of foreclosure orders in working-class neighborhoods, and the forced sale of personal property, drew neighbors who attempted to disrupt the proceedings as a form of protest of the action and support of the family under the eviction notice. The angry crowds also had the effect of scaring off potential bidders for auction goods. While this allowed neighbors to pay pennies on the dollar for their neighbors' possessions (which were usually given back to the family following the sale), it also did little to reduce the debt of the family being evicted.

The wealthy, who had significant investments in Wall Street, did experience losses; however those losses depended on how investments were structured. As a result, all but the very well-off curtailed their spending habits.

For example, high end consumer goods providers, such as the luxury automobile industry, saw their sales number dwindle to levels far below the previous levels of the twenties, resulting in layoffs of salaried and hourly workers. The best example of this collapse was the automobile industry in Cleveland, Ohio, which had the highest concentration of luxury automobile manufacturers outside of Detroit. Between 1929 and 1934 production of Peerless, Jordan, Stearns-Knight all failed; Peerless, as a company, did survive, but did so by discontinuing automobile production and regrouping as a brewery.

Purchases of even basic cars, those manufactured by the middle and entry level marques, also slowed. General Motors attempted to encourage consumers to buy cars by advertising that “the sale of one car keeps an autoworker employed for three months, allowing that worker and his family to buy goods and services with their salary.” However a sizable percentage of Americans couldn't even pay for a tank of gas, let alone a new car and the entire auto industry struggled to maintain sales at a profitable level.

Drought first struck the Eastern United States in 1930. By 1931 it began moving westward where the weather pattern stalled over the Great Plains states. By 1934, the plains had been turned to desert. While weather was the catalyst for the Dust Bowl (a named coined in 1935), the root cause was poor farming and soil conservation techniques on land that was better suited to growing prairie grasses and native flowers than it was for growing corn. When the thin layer of top soil turned to a dry powder, and the winds swept through, dust storms resulted producing a filth and grime that was difficult to wash out fabric and clean out of buildings. Once the top soil was depleted, the under layer of clay that remained proved unsuitable for cash crops, leading to farm failures and mortgage foreclosures.

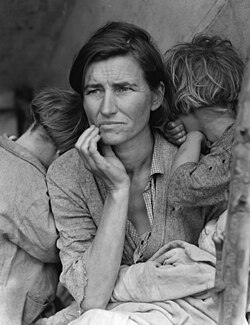

Those who had lost their homes and livelihoods were lured westward by advertisements for work put out by agribusiness in western states such as California. The migrants came to be called Okies, Arkies, and other derogatory names as they flooded the labor supply of the agricultural fields, driving down wages and increasing competition for jobs in areas that couldn't afford it. This story was dramatized in the famous novels The Grapes of Wrath and Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck.

In the South, rural workers and share croppers migrated north by train with plans to work in auto plants around Detroit. In the Great Lakes states, farmers had been experiencing depressed market conditions for their crops and goods since the end of World War I. Family farms that had been mortgaged during the Twenties to provide money to “get through until better times” risked foreclosure when their owners failed to make payments. Unlike the dustbowl states, the midwest experienced near normal weather conditions in the 1930s, and farmers could make a living if they spent their incomes in a wise and prudent way. Unable to pay wages for hired help, families whose farms were located near railroad tracks often hired men who volunteered to work for food.

However, a large percentage of the American middle class was able to survive the ordeal. Those in professions where skills and jobs were considered “depression proof” (government positions, teachers in well funded districts, doctors, lawyers, etc.) continued to work. Daily life was made more secure if these workers had little debt before the stock market crash, had liquid savings and generally lived without overt extravagances. American middle class households managed to get through the economic depression by adapting to conditions, spending wisely and avoiding unnecessary purchases.

One industry that flourished in America during the 1930s was the movie industry (Hollywood). The emergence of sound films in the late 1920s, combined with the escapism that film provided to a nation down on its luck, made the film industry one of the few that produced profits throughout the 1930s. Films commonly featured rich sets and carefree characters, allowing an increasingly depression-weary nation to leave its cares behind -- if only for the duration of a movie. Shirley Temple's films were leading attractions, perhaps because her characters' unwavering hopefulness in the face of trying circumstances spoke to American audiences. Conversely, the film version of Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath (see above), now considered by many to be a masterpiece of American cinema, was a commercial disappointment when it debuted -- possibly because it reminded too many moviegoers of the harsh realities of their own situations.

Movie genres that thrived during the 1930s were screwball comedies, lavish musicals, westerns and gangster movies.

End of the Great Depression

In the United States

For further details, see the main New Deal article.

It was not until the U.S. entered World War II that Roosevelt's ideas for massive public expenditures and deficit spending truly began to bear fruit. Roosevelt's administration, of course, had little choice but to increase expenditures, given the war effort. Even given the special circumstances of war mobilization, New Deal policies seemed to work exactly as predicted, winning over many Republicans, who had been the New Deal's greatest opponents. When the Great Depression was brought to an end by the Second World War, it was obvious that the turnaround had been caused primarily by the reinforcement of business through government expenditure.

In truth Roosevelt had foreseen from early in his Presidency that only a solution to the international trade problem would finally end the depression, and that the New Deal was, to no small extent, a "holding action". He contemplated precipitating a war with Japan early on, in hopes of dealing with the problem early. However, the intensity of the economic crisis convinced him that before the world situation could be dealt with, the United States would have to put its own fiscal house back in order. His original conception was that the New Deal would restore circumstances which would allow for a return to balanced budgets and an international gold standard. It was only gradually that he came to the conclusion that it was essential to remake the U.S. economy in a more extensive fashion, particularly because of the "Roosevelt Recession" of 1937, when he had balanced the budget by restricting fiscal support to the economy.

Thus the statement "it was World War II that ended the Depression", while often asserted by partisans as proof that the New Deal "failed" is, in fact, the view that the architects of the New Deal themselves saw as the reality: that as long as Europe was marching towards war, Japan was engaged in imperial conquest, and the international debt and trading system were still organized in an attempt by creditors to be paid back for World War I at pre-war values for gold, that a full solution to the economic crisis was impossible.

New Deal programs sought to stimulate demand and provide work and relief for the impoverished through increased government spending, by:

- instituting regulations which ended what was called "cut throat competition" (in which large players supposedly used predatory pricing to drive out small players);

- creating regulations which would raise the wages of ordinary workers, to redistribute wealth so that more people could purchase products.

The original implementation, in the form of the National Recovery Act, brought in direct unemployment relief, and allowed:

- business to set price codes;

- the NRA board to set labor codes and standards;

- the Federal government to insure the banking system and provide price supports for agriculture and mining.

This is referred to as the First New Deal. It was centered around the use of the alphabet soup of agencies set up in 1933 and 1934, along with the use of previous agencies, to regulate and stimulate the economy.

The theories behind the New Deal matched the later prescriptions of British economist John Maynard Keynes, who advocated increased government spending in a financial crisis. In 1929 federal expenditures constituted only 3% of the GDP. Between 1933 and 1939, federal expenditure tripled, and Roosevelt's critics accused him of turning America into a socialist, or even Stalinist state. The primary purpose of the New Deal were as follows: to prevent the economy and banking system from going into a free fall; to provide effective relief until larger economic forces would end the slump; and to prevent those factors which had exacerbated the slump. The New Deal was both a program of national recovery and of reform. An interesting insight into what motivated Roosevelt came from the transition from the Hoover administration — both men agreed that it was a global maladjustment of prices, debts and production that was causing the slump. The disagreement came over whether the US government should act first to try and negotiate an end to the root causes internationally, which was Hoover's view, or act for domestic recovery and reform until the international situation could be resolved, which was FDR's view.

The New Deal was rooted in new ideas, but also in economic orthodoxy of balanced budgets, and restraint of federal power. It represented bigger and broader government than ever before, but not as big as government would later become: spending on the New Deal was far smaller than on the war effort. In short, federal expenditures went from 3% of the GDP in 1929 to about 33% in 1945. The big surprise was just how productive America became: spending financially cured the depression. Between 1939 and 1944 (the peak of wartime production), the nation's output more than doubled. Consequently, unemployment plummeted—from 19% in 1938 (already down from 1933's 24.9% peak) to 1.2% in 1944—as the labor force grew by ten million. The war economy showed just how large the fiscal stimulus required to end the downturn of the Depression was, and it led, at the time, to fears that as soon as America demobilized, that it would return to Depression conditions and industrial output would fall to its pre-war levels. There is general agreement that it was World War II which finally provided the United States Federal Government with the political will to buy its way out of the Depression and resolve the global monetary crisis by the imposition of the Bretton Woods system.

Films and TV

- Cradle Will Rock, Director: Tim Robbins, 1999

- The Grapes of Wrath, Director: John Ford, 1940

- The Journey of Natty Gann, 1985

- Of Mice and Men, filmed three times - in 1939, 1981 and 1992

- They Shoot Horses, Don't They?, Director: Sidney Pollack, 1969

- The Crash of 1929 -- PBS [1]

- Carnivàle (2003-2005) fictional account of Depression era television series produced by HBO

- Dogville 2003, Director:Lars von Trier

See also

- Aftermath of World War I

- Business cycle

- Economic collapse

- Great Depression in Canada

- Great Depression in Australia

- Great Depression in the United Kingdom

- Great Depression in the United States

- Great Depression in France

- Great Depression in Italy

- Great Depression in Ireland

- Great Depression in Spain

- Great Depression in Latin America

- Great Depression in Germany

- Great Depression in Scandinavia

- Great Depression in South Africa

- Great Depression in Eastern Europe

- Great Depression in East Asia

- Great Depression in Japan

- New Deal

External links

- American Economic Policy from the Great Depression to NAFTA

- America's Great Depression — an "Austrian" interpretation by Murray Rothbard

- America's Great Depression — Timeline

- The Causes of the 1929–33 Great Collapse: A Marxian Interpretation, by James Devine

- Keynes and Friedman on the Great Depression

- Theories on the Great Depression

- The Economics of the Great Depression

- About.com: 1929 Stock Market Crash

- The Great Depression (ingrimayne.saintjoe.edu)

- The Dirty Thirties — Images of the Great Depression in Canada

- The Main Causes of the Depression

- Depression unemployment rates, from U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics