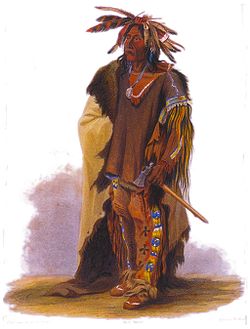

Sioux

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

The Sioux (also Dakota) are a Native American tribe. They form one of three groups of seven tribes (the Great Sioux Nation or Seven Council Fires) that speak three different varieties of the Sioux language, including the Lakota, Santee, and Yankton-Yanktonai.

Contents |

Synonymy

The name Sioux is an abbreviated form of Nadouessioux borrowed into French Canadian as Nadoüessioüak from the early Ottawa exonym: na·towe·ssiwak "Sioux". The Proto-Algonquian form *na·towe·wa meaning "Northern Iroquoian" has reflexes in several daughter languages that refer to a small rattlesnake (massasauga, Sistrurus). This information was interpreted by some that the Ottawa borrowing was an insult. However, this proto-Algonquian term most likely is ultimately derived from a form *-a·towe· meaning simply "speak foreign language", which was later extended in meaning in some Algonquian languages to refer to the massasauga. Thus, contrary to many accounts, the Ottawa word na·towe·ssiwak never equated the Sioux with snakes.

Today many of the tribes continue to officially call themselves Sioux which the Federal Government of the United States applied to all Yankton/Yanktonai/Santee/Lakota people in the 19th and 20th centuries. However, some of the tribes have formally or informally adopted traditional names: the Rosebud Sioux Tribe is also known as the Sicangu Oyate (Brule Nation), and the Oglala often use the name Oglala Lakota Oyate, rather than the English "Oglala Sioux Tribe" or OST. (The alternate English spelling of Ogallala is not considered proper.)

The earlier linguistic 3-way division of the Dakotan branch of the Siouan family identified Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota as dialects of a single language, where Lakota = Teton, Dakota = Santee & Yankton, Nakota = Yanktonai & Assiniboine. This classification was based in large part on the each group's particular pronunciation of the autonym Dakhóta-Lakhóta-Nakhóta. However, more recent research has shown that Assiniboine (and also Stoney) are not mutually intelligible with the Sioux groups, while the Yankton-Yanktonai, Santee, and Teton groups all spoke mutually intelligible varieties of a Sioux idiom. This more recent classification identifies Assiniboine and Stoney as two separate languages with Sioux being the third language that has three similar dialects: Teton, Santee-Sisseton, Yankton-Yanktonai. Furthermore, The Yankton-Yanktonai never referred to themselves with the using the pronunciation Nakhóta but rather pronounced it the same as the Santee (i.e. Dakhóta). (Assiniboine and Stoney speakers use the pronunciation Nakhóta or Nakhóda.)

The term Dakota has also been applied by anthropologists and governmental departments to refer to all Sioux groups, resulting in names such as Teton Dakota, Santee Dakota, etc. This was due in large part to the misrepresented translation of the Ottawa word from which Sioux is derived (supposedly meaning "snake", see above).

The Yankton, Yanktonai, Santee, and Lakota have names for their own subdivisions. The "Yankton" received this name which meant people from the villages of far away. The "Santee" received this name from camping for long periods in a place where they collected stone for making knives. The "Tetonwan" were known as people who moved west with the coming of the horse to live and hunt buffalo on the prairie. From these three principal groups, came seven sub-tribes.

Social divisions

The Yankton-Yanktonai, the smallest division, reside on the Yankton reservation in South Dakota and the Northern portion of Standing Rock Reservation, while the Santee live mostly in Minnesota and Nebraska, but include bands in the Sisseton-Wahpeton, Flandreau, and Crow Creek Reservations in South Dakota. The Lakota are the westernmost of the three groups, occupying lands in both North and South Dakota.

Yankton-Yanktonai

The Yankton-Yanktonai are a branch of Sioux peoples who moved into northern Minnesota. They originally constituted two main tribes: the Yankton ("campers at the end") and Yanktonai ("lesser campers at the end"). Economically, they were involved in quarrying pipestone.

During the 19th Century, these people migrated or were forced west into Santee Territory, and today, the Yankton Sioux Tribe occupies a reservation "without boundaries" on the east bank of the Missouri in south-central South Dakota. The Yanktonai are scattered in a number of reservations in North and South Dakota.

Santee (Dakota)

The Santee (a.k.a. Dakota) people migrated north and westward from the south and east into Ohio then to Minnesota. The Santee were a woodland people who thrived on hunting, fishing and subsistence farming. Migrations of Anishinaabe/Chippewa people from the east in the 17th and 18th centuries, with rifles supplied by the French and English, pushed the Santee further into Minnesota and west and southward, giving the name "Dakota Territory" to the northern expanse west of the Mississippi and up to its headwaters. The western Santee obtained horses, probably in the 17th century (although some historians date the arrival of horses in South Dakota to 1720), and moved further west, onto the Great Plains, becoming the Titonwan tribe, subsisting on the buffalo herds and corn-trade with their linguistic cousins, the Mandan and Hidatsa along the Missouri.

In the 19th century, as the railroads hired hunters to exterminate the buffalo herds, the Indians' primary food supply, in order to force all tribes into sedentary habitations, the Santee and Lakota were forced to accept white-defined reservations in exchange for the rest of their lands, and domestic cattle and corn in exchange for buffalo, becoming dependent upon annual federal payments guaranteed by treaty.

In 1862, after a failed crop the year before and a winter starvation, the federal payment was late to arrive. The local traders would not issue any more credit to the Santee and the local federal agent told the Santee that they were free to eat grass. As a result on August 17, 1862, the Sioux Uprising began when a few Santee men attacked a white farmer, igniting further attacks on white settlements along the Minnesota River. Some 450 farmers, mostly German immigrants, were massacred until state and federal forces put the revolt down. Courts-martial tried and condemned 303 Santee for war crimes. On November 5, 1862 in Minnesota, in court martials, 303 Santee Sioux were found guilty of rape and murder of hundreds of white farmers and were sentenced to hang. President Abraham Lincoln remanded the death sentence of 285 of the warriors, signing off on the execution of 38 Santee men by hanging on December 29, 1862 in Mankato, Minnesota, the largest mass execution in US history.

During and after the revolt, many Santee and their kin fled Minnesota and Eastern Dakota, joining their relatives in the West, or settling in the James River Valley in a short-lived reservation before being forced to move to Crow Creek Reservation on the east bank of the Missouri. Others were able to remain in Minnesota and the east, in small reservations existing into the 21st Century, including Sisseton-Wahpeton, Flandreau, and Devils Lake (Spirit Lake or Fort Totten) Reservations in the Dakotas. Some ended up eventually in Nebraska, where the Santee Sioux Tribe today has a reservation on the south bank of the Missouri.

Lakota (Teton)

- See: Lakota.

Sioux Nation

The Sioux Nation consists of divisions, each of which may have distinct bands, the larger of which are divided into sub-bands.

- Santee division

- Mdewakantonwan

- Sisitonwan

- Wahpekute

- Wahpetonwan

- Yankton-Yanktonai

- Ihanktonwan (Yankton)

- Ihanktonwana (Yanktonai or Little Yankton)

- Stoney (Canada)

- Assiniboine (Canada)

- Lakota (Teton)

- Hunkpapa

- notable persons: Tatanka Iyotake

- Oglala

- notable persons: Tasunka witko, Makhpyia-luta, Hehaka Sapa and Billy Mills (Olympian)

- Payabya

- Tapisleca

- Kiyaksa

- Wajaje

- Itesica

- Oyuhpe

- Wagluhe

- Sihasapa (Blackfoot Sioux)

- Sichangu (French: Brulé) ("burnt thighs")

- Upper Sichangu

- Lower Sichangu

- Miniconjou

- Itazipacola (French: Sans Arcs "No Bows")

- Oohenonpa (Two-Kettle or Two Boilings)

- Hunkpapa

Reservations

Today, one half of all Enrolled Sioux live off the Reservation.

Lakota reservations recognized by the US government include:

- Oglala (Pine Ridge Indian Reservation)

- Brulé (Rosebud Indian Reservation)

- Hunkpapa (Standing Rock/Cheyenne River)

- Miniconju (Cheyenne River)

- Sans Arc (Cheyenne River)

- Two-Kettle (Cheyenne River)

- Santee

- Yanktonai (Yankton)

- Flandreau

- Sisseton-Wahpehton

- Lower Sioux

- Upper Sioux

- Shakopee

- Prairie Island

Derived placenames

The U.S. states of North Dakota and South Dakota are named after the name Dakota. Two other U.S. states have names of Siouan origin: Minnesota is named from mni ("water") plus sota ("hazy/smoky, not clear"), while Nebraska is named from a language close to Santee, in which mni plus blaska ("flat") refers to the Platte (French for "flat") River. Also, the states Kansas, Iowa, and Missouri are named for cousin Siouan tribes, the Kansa, Iowa, and Missouri, respectively, as are the cities Omaha, Nebraska and Ponca City, Oklahoma. The names vividly demonstrate the wide dispersion of the Siouan peoples across the Midwest U.S.

More directly, several Midwestern municipalities utilize Sioux in their names, including Sioux City (IA), Sioux Center (IA) and Sioux Falls (SD). Midwestern rivers include the Little Sioux River in Iowa and Big Sioux River along the Iowa/South Dakota border.

Many smaller towns and geographic features in the Northern Plains retain their Sioux names or bear English translations of those names, including Wasta, Owanka, Oacoma, Hot Springs (Minnelusa), Minnehaha County, Belle Fourche (Mniwasta, or "Good water"), Inyan Kara, and others.

Media

|

See also

External links

- The Yanktonai (Edward S. Curtis)

- Lakota Language Consortium

- Winter Counts a Smithsonian exhibit of the annual icon chosen to represent the major event of the past year

Bibliography

- Albers, Patricia C. (2001). Santee. In R. J. DeMallie (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 2, pp. 761-776). W. C. Sturtevant (Gen. Ed.). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-050400-7.

- Christafferson, Dennis M. (2001). Sioux, 1930-2000. In Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 2, pp. 821-839). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- DeMallie, Raymond J. (2001a). Sioux until 1850. In Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 2, pp. 718-760). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- DeMallie, Raymond J. (2001b). Teton. In Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 2, pp. 794-820). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- DeMallie, Raymond J. (2001c). Yankton and Yanktonai. In Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 2, pp. 777-793). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- DeMallie, Raymond J.; & Miller, David R. (2001). Assiniboine. In Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 1, pp. 572-595). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Getty, Ian A. L.; & Gooding, Erik D. (2001). Stoney. In Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 1, pp. 596-603). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Parks, Douglas R.; & Rankin, Robert L. (2001). The Siouan languages. In Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 1, pp. 94-114). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.