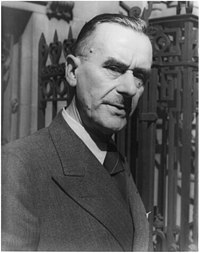

Thomas Mann

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

- For other people named Thomas Mann, see Thomas Mann (disambiguation).

Paul Thomas Mann (June 6, 1875 – August 12, 1955) was a German novelist, social critic, philanthropist and essayist, lauded principally for a series of highly symbolic and often ironic epic novels and mid-length stories, noted for their insight into the psychology of the artist and intellectual and an underlying eroticism informed by Mann's own struggles with his sexuality. He is noted for his analysis and critique of the European and German soul in beginning of the 20th century using modernized German and Biblical myths as well as the ideas of Goethe, Nietzsche, and Schopenhauer.

Contents |

Life

Mann was born in Lübeck, second son of Thomas Johann Heinrich Mann (a senator and grain merchant) and his wife Júlia da Silva Bruhns (who came from a German-Portuguese-Creole family). Mann's father died in 1891 and his trading firm was liquidated. The family subsequently moved to Munich, where Mann lived from 1891 until 1933, with the exception of a year-long stay in Palestrina, Italy, with his older brother Heinrich, also a novelist. Mann attended the science division of a Lübeck gymnasium, then spent some time at the University of Munich where in preparation for a career in journalism he studied history, economics, art history, and literature. He then worked with the south German Fire Insurance Company 1894-95. His career as a writer started when he wrote for Simplicissimus. Mann's first short story, Little Herr Friedmann (Der Kleine Herr Friedemann) was published in 1898.

In 1905, he married Katia Pringsheim, daughter of a prominent, secular Jewish family of intellectuals. They had six children (Erika, Klaus, Golo, Monika, Elisabeth and Michael) who were highly intelligent and literary or artistic in their own right. He emigrated from Nazi Germany to Küsnacht near Zürich, Switzerland, in 1933, then in 1942 to Pacific Palisades, California, USA. In 1944, he became a naturalized citizen of the United States. He returned to Europe in 1952.

He was never to live in Germany again, though he traveled there regularly and was widely celebrated. On his return to Europe, he lived in Kilchberg, near Zürich, where he died in 1955.

He won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1929, in large part for his achievement in the epic Buddenbrooks (1901), about the decline of a bourgeois family over several generations. Other major works include The Magic Mountain (originally Der Zauberberg, 1924), set in a highly symbolic sanatorium that portrays the conflicts at the heart of European civilization at the time, Lotte in Weimar (1939) in which he returned to the world of Goethe's novel The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774), Doktor Faustus (1947), the story of composer Adrian Leverkühn and the progressive destruction of German culture in the two World Wars, and The Confessions of Felix Krull (originally Bekenntnisse des Hochstaplers Felix Krull, 1954) which was left unfinished upon his death.

One of his greatest works was the tetralogy Joseph and His Brothers (Joseph und seine Brüder) 1933–42, set in the biblical world. The story about the conflict between personal freedom and political tyranny was based on Genesis 12-50. The first volume recounts the early history of Jacob, and introduces then Joseph, the central character. He is sold to the Egypt, where he refuses Potiphar's advances and gains her enmity. Joseph develops into a wise man and the savior of his people.

Mann's diaries, unsealed in 1975, speak movingly of his own struggles with his sexuality, which found reflection in his works, especially through the obsession of the elderly Aschenbach for the young Polish boy, Tadzio, in his novella, Death in Venice (originally Der Tod in Venedig, 1912). Anthony Heilbut's biography, Thomas Mann: Eros and Literature (1997), was widely acclaimed for uncovering the centrality of Mann's sexuality to his oeuvre. Mann himself described his feelings for young violinist and painter Paul Ehrenberg as the "central experience of my heart." However, he chose marriage and family. His works also deal with other sexual themes, such as incest in such works as "Wälsungenblut".

Mann was a true humanist who valued literature and believed in the necessity of protecting civilization against the ignorant forces of barbarity. By reading his works, one can gain a fuller knowledge, and deeper understanding of his rich literary world. And in his own words: "The value and significance of my work for posterity may safely be left to the future; for me they are nothing but the personal traces of a life led consciously, that is, conscientiously." (Thomas Mann, upon receiving the Nobel Prize)

"A man lives not only his personal life, as an individual, but also, consciously or unconsciously, the life of his epoch and his contemporaries." (from The Magic Mountain, 1924)

"Regarded as a whole, Mann's career is a striking example of the "repeated puberty" which Goethe thought characteristic of the genius, In technique as well as in thought, he experienced far more daringly than is generally realized. In Buddenbrooks he wrote one of the last of the great "old-fashioned" novels, a patient, thorough tracing of the fortunes of a family." (from Thomas Mann by Henry Hatfield, 1962)

"I always feel a bit bored when critics assign my own work so definitely and completely to the realm of irony and consider me an ironist through and through, without also taking account of the concept of humor." (Thomas Mann, from Harold Bloom's How to Read and Why, 2000

Politics

Unlike his brother Heinrich, it has been claimed that Thomas never truly engaged with the politics of his day. Heinrich was an overt Communist, whereas Thomas was criticised for not condemning the Nazi regime enough. Despite this, Mann's books, particularly Buddenbrooks, were amongst the many burnt by Hitler's regime, and his move to Switzerland was due to the rise of National Socialism in Germany. During World War I Mann supported Kaiser's policy and attacked liberalism. In VON DEUTSCHER REPUBLIK (1923), as a semi-official spokesman for parliamentary democracy, he called the German intellectual to support the new Weimar state.

Influences

- The Bible

- Fyodor Dostoevsky

- Theodor Fontane

- Sigmund Freud

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

- E.T.A. Hoffmann

- Carl Jung

- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing

- Martin Luther

- Friedrich Nietzsche

- Edgar Allan Poe

- Friedrich von Schlegel

- Arthur Schopenhauer

Works

- Little Herr Friedemann (1897) = Der kleine Herr Friedemann

- The Clown (1897) = Der Bajazzo

- The Road to the Churchyard (1900) = Der Weg zum Friedhof

- Buddenbrooks (1901) = Buddenbrooks - Verfall einer Familie

- Gladius Dei (1902)

- Tristan (1903)

- Tonio Kröger (1903)

- Royal Highness (1909) = Königliche Hoheit

- Death in Venice (1912) = Der Tod in Venedig

- Reflections of an Unpolitical Man (1918) = Betrachtungen eines Unpolitischen

- The German Republic (1922) = Von deutscher Republik

- The Magic Mountain (1924) = Der Zauberberg

- Disorder and Early Sorrow (1926) = Unordnung und frühes Leid

- Mario and the Magician (1930) = Mario und der Zauberer

- Joseph and His Brothers (1933-43) = Joseph und seine Brüder

- The Tales of Jacob (1933)

- The Young Joseph (1934)

- Joseph in Egypt (1936) = Joseph in Ägypten

- Joseph the Provider (1943) = Joseph, der Ernährer

- The Problem of Freedom (1937) = Das Problem der Freiheit

- The Coming Victory of Democracy (1938)

- Lotte in Weimar: The Beloved Returns (1939)

- The Transposed Heads (1940) = Die vertauschten Köpfe - Eine indische Legende

- Listen Germany! (1942) = Deutsche Hörer

- Doctor Faustus (1947) = Doktor Faustus

- The Holy Sinner (1951) = Der Erwählte

- Confessions of Felix Krull Confidence Man, The Early Years (1922/1954) = Bekenntnisse des Hochstaplers Felix Krull. Der Memoiren erster Teil (unfinished)

External links