Amtrak

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

- For other uses, see Amtrak (disambiguation).

| Amtrak | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Reporting marks | AMTK |

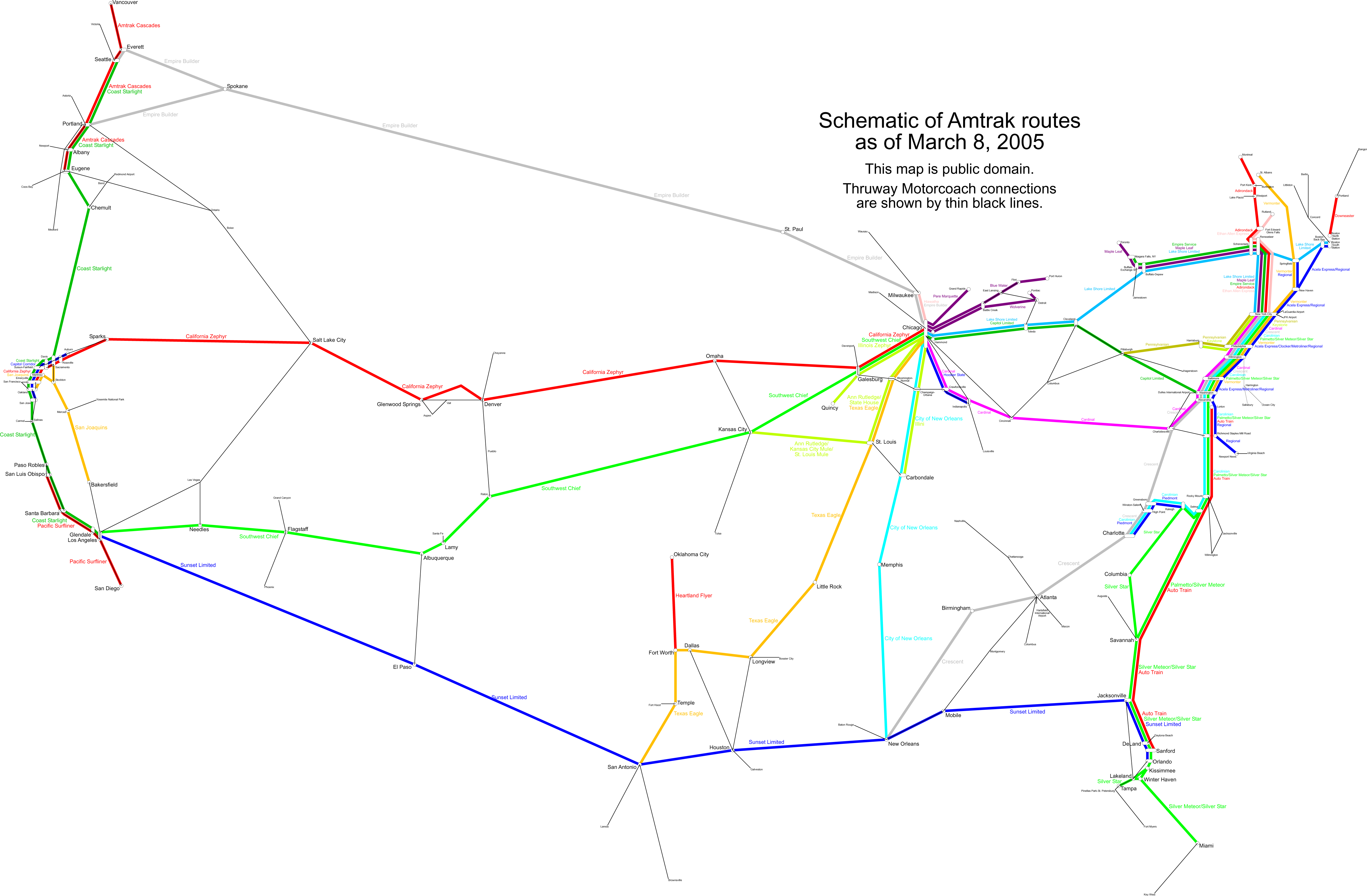

| Locale | continental United States, as well as routes to Vancouver, Toronto, and Montreal |

| Dates of operation | 1971 – present |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8½ in (1435 mm) (standard gauge) |

| Headquarters | Washington, D.C. |

Amtrak is the trademark name of the intercity passenger train system created on May 1, 1971 in the United States. Formally known as the National Railroad Passenger Corporation, the trademark name Amtrak is a portmanteau of the words American travel by track.

Nominally, Amtrak is an independent for-profit corporation, but all of its preferred stock is owned by the federal government, and the members of Amtrak's board of directors are appointed by the President of the United States and are subject to confirmation by the United States Senate. Some common stock is held by private railroads and other investors, although it is not actively traded and is generally considered to be worthless as an investment, as it has never paid dividends.

The President of Amtrak is David L. Gunn. The current chairman of Amtrak's board is David Laney, a presidential appointee.

Contents |

Historic background

Amtrak was created to relieve private railroad companies of their previous legal obligation to provide passenger rail service as common carriers and allow them to pursue their interests in more profitable freight operations. It was planned from the outset that Amtrak trains would continue to use the existing network of tracks in the freight rail system. For the most part, this scheme still exists today, and in most parts of the United States Amtrak trains share tracks with the freight-oriented host railroads.

Historically, on routes where a single railroad has had an undisputed monopoly, passenger service was as spartan and as expensive as the market would bear, since such railroads had no need to advertise their freight services. But on routes where two or three railroads were in direct competition with each other for freight business, such railroads would spare no expense to make their passenger trains as fast, luxurious, and affordable as possible, because it was considered to be the most effective way of advertising their profitable freight services.

As early as the 1930s, automobile travel had begun to cut into the rail passenger market, somewhat reducing economies of scale, but it was the development of the Interstate Highway System and of commercial aviation in the 1950s and 1960s that dealt the most damaging blows to rail transportation, both passenger and freight. There was little point in operating passenger trains to advertise freight service when those who made decisions about freight shipping traveled by car and by air, and when the railroads' chief competitors for that market were interstate trucking companies. Soon, the only things keeping most passenger trains running were legal obligations. Meanwhile, companies who were interested in using railroads for profitable freight traffic were looking for ways to get out of those legal obligations, and it looked like passenger rail service would soon become extinct in the United States.

The National Association of Railroad Passengers (NARP) was formed in 1967 to lobby for the continuation of passenger trains. Its lobbying efforts were hampered somewhat by Democratic opposition to any sort of subsidies to the privately-owned railroads, and Republican opposition to nationalization of the railroad industry. The proponents were aided by the fact that few in the federal government wanted to be held responsible for the seemingly-inevitable extinction of the passenger train, which most regarded as tantamount to political suicide.

On October 30, 1970, President Richard M. Nixon signed a law creating Amtrak. At the time, it was thought that it would give passenger trains one last hurrah, and allow the President and Congress to save face, then quietly disappear. Many insiders, including President Nixon's aides, assumed that Amtrak would disappear within two years of its creation. However, popular and political support for Amtrak has persisted while subsidies from both federal and state governments have helped Amtrak to survive and grow.

The bill creating Amtrak, the Rail Passenger Service Act of 1970, permitted railroads to buy into the new corporation using a formula based on their recent intercity passenger losses. Any railroad who contracted with Amtrak was permitted to discontinue all intercity passenger service after May 1, 1971 except those services chosen and paid for by Amtrak as part of its nationwide system. Railroads who chose not to join Amtrak were required to continue operating their existing passenger service until 1975.

At Amtrak's startup, 20 of the 26 eligible railroads had elected to join the Amtrak system:

- Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway

- Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (no service until the West Virginian began September 8, 1971)

- Burlington Northern Railroad

- Central of Georgia Railway (has never hosted Amtrak service)

- Chesapeake and Ohio Railway

- Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad

- Chicago and North Western Railway (never had any service)

- Delaware and Hudson Railway (no Amtrak service until the Adirondack began August 6, 1974)

- Grand Trunk Western Railroad (no Amtrak service until the Blue Water Limited began September 15, 1974)

- Gulf, Mobile and Ohio Railroad

- Illinois Central Railroad

- Louisville and Nashville Railroad

- Missouri Pacific Railroad

- Norfolk and Western Railway (no Amtrak service until the Mountaineer began March 25, 1975)

- Northwestern Pacific Railroad (has never hosted Amtrak service)

- Penn Central Transportation

- Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad

- Seaboard Coast Line Railroad

- Southern Pacific Railroad

- Union Pacific Railroad

The Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad, Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad, Georgia Railroad and Southern Railway continued to run their own intercity trains after the Amtrak startup date.

The Southern joined on February 1, 1979, when its Southern Crescent became Amtrak's Crescent. The D&RGW last operated its Rio Grande Zephyr April 25, 1983, and Amtrak's San Francisco Zephyr was renamed the California Zephyr; the train was rerouted to use the DRG&W July 15, 1983 (delayed by a mudslide). The bankrupt CRI&P ran its last passenger trains (the Peorian and a Chicago-Rock Island train) December 31, 1978 and was liquidated in 1980. The last Georgia Railroad mixed train was operated May 6, 1983 by the Seaboard System Railroad The Erie Lackawanna's Port Jervis-Hoboken trains were considered commuter trains and were operated by the New York MTA.

In its original conception, Amtrak owned no track and thus was not truly a railroad. Following the bankruptcy declaration of several northeastern railroads in the early 1970s — particularly that of Penn Central, which owned and operated the Northeast Corridor, Congress passed the Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act of 1976 to create a consolidated, federally-subsidized freight network called Conrail. As part of this legislation, the vital Northeast Corridor passenger route was transferred to Amtrak, and the corporation became a true railroad for the first time. In subsequent years, various short route segments needed for passenger operations but not for freight were transferred to Amtrak ownership. However, the majority of Amtrak's routes are hosted by private railroads, to which Amtrak pays the costs of adding its passenger trains to the freight trains of the host railroad.

At the beginning in 1971, the host railroads supplied the rolling stock and operating crews. Amtrak soon purchased the best of the railroad equipment and subsequently has purchased new equipment.Today, Amtrak trains are staffed by Amtrak employees but, other than on the routes that Amtrak owns outright, are dispatched by the host railroads on whose tracks these trains operate.

The fuel shortages of the mid-1970s on the nation's highways and increased air fares which also resulted in creating a renewed interest in passenger rail travel. Given that railroads used fuel very efficiently, passenger rail travel no longer seemed quite so outmoded. Consequently, Amtrak's ridership began to increase. Another rebound occurred after the September 11, 2001 attacks.

Conflicting goals

Amtrak was established to relieve railroads of their federally-mandated responsibility to transport passengers as a priority over freight. This was causing increasingly large financial losses for the railroads as the networks of federally-funded highways and airports expanded. From the outset, Amtrak was expected to pursue conflicting goals: Amtrak was supposed to provide a national rail passenger service while simultaneously operating as a commercial enterprise.

There have been few times in history when any intercity rail passenger operation in the world has been truly profitable, even with respect to only its operating costs, and passenger trains have never brought in enough revenue to pay for their infrastructure costs. Even highly efficient private-sector railroads such as the Norfolk and Western Railway could not earn a profit, or even recover operating expenses for passenger service. The concept of Amtrak as a for-profit business was fatally flawed before the first passenger boarded.

Amtrak is in many ways dependent on freight railroads. As it owns little track, it must rely on maintenance done by the freight owners, and sometimes has to cancel service over routes taken out-of-service by the host freight railroad (as occurred recently with service to Phoenix, Arizona) or pay to maintain the tracks.

Politically-appointed leaders and congressional funding

Without a dedicated source of capital equipment and operating funding (except for competitive passenger fares and even less express income), Amtrak's continued operation has always been dependent upon the Executive and Legislative branches of the U.S. government. Both congressional funding and appointments of Amtrak's leaders are subject to political considerations, which have varied widely during its existence through seven U.S. presidencies and major shifts of power in the U.S. Congress.

Because Amtrak's board and president are all political appointees, some have had little or no experience with railroads. However, Amtrak has also benefited from both highly skilled and politically-oriented leaders.

For example, in 1982, former U.S. Secretary of the Navy and retired Southern Railway head W. Graham Claytor Jr. brought his naval and railroad experience to the job. Claytor had served briefly as an acting U.S. Secretary of Transportation in the cabinet of President Jimmy Carter in 1979, and came out of retirement to lead Amtrak after the disastrous financial results during the Carter administration (1977-1981). He was recruited and strongly supported by John H. Riley, an attorney who was the highly-skilled head of the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) under the Reagan Administration from 1983-1989. Secretary of Transportation Elizabeth Dole also tacitly supported Amtrak. Claytor seemed to enjoy a good relationship with the Congress for his 11 years in the position. Of course, politics aside, that may have also been because he did a good job. According to an article in Fortune magazine, through vigorous cost cutting and aggressive marketing, within 7 years under Claytor, Amtrak was generating enough cash to cover 72% of its $1.7 billion operating budget by 1989, up from 48% in 1981. [2]

Myth of a self-sustaining Amtrak

Two of the leaders who followed Claytor lacked freight railroad or private-sector experience. Further, they each inherited the goal of making Amtrak operationally self-sufficient, an idea which began under David Stockman and his successors at the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) while Claytor was Amtrak's president (circa 1986).

Claytor's replacement was Thomas Downs. Mr Downs had been City Administrator of Washington DC, and oversaw the Union Station project, which had experienced both massive delays and cost overruns. Under Downs, Amtrak began to claim that it could achieve operating self-sufficiency, and its leaders seemed to be increasingly misleading as to the prospects of achieving that goal when pressed by Congress and the media.

After Downs left Amtrak, George Warrington was appointed by the board as the company's next president. He had previously been in charge of Amtrak's Northeast Corridor Business Unit. When he took the helm of Amtrak in January, 1998, self-sufficiency was still officially a stated goal, although it was becoming elusive in the eyes of Congress. Under Warrington's administration, Amtrak was mandated by the Administration and Congress to become totally self-sufficient within a five-year period, and all its management efforts were directed to that goal. Passengers became "guests" and there were expansions into express freight work. Finally, at the end of the 5-year period, it became clear that self-sufficiency was an unachievable goal, no matter how much additional express revenue was gained or how many cuts were made in Amtrak services.

In fairness, while both Downs and Warrington had extensive experience in government, neither had the non-governmental cost accounting or practical experience in private-sector railroading that Claytor had had. Claytor also enjoyed the benefit of serving during the Reagan Administration when increases in federal spending on military items was drawing a lot of the political attention in Congress.

The efforts to expand Amtrak's express income were unpopular with the host freight railroads, who did not want the additional Amtrak traffic it brought (or the competition). The express work also brought Amtrak new political enemies in the powerful trucking lobby before Congress. Warrington also had the burden of delays in implementation of the new Acela Express high-speed trainsets, which promised to be a strong source of income and favorable publicity along the Northeast Corridor between Boston and Washington DC.

Gunn administration: reality check

When David L. Gunn was selected as Amtrak president in April 2002, Amtrak self-sufficiency had largely fallen out of favor as a realistic short-term goal. He came with a reputation as a strong, straight-forward and experienced operating manager but with a style sometimes putting him at odds with others. Years earlier, Gunn's refusal to "do politics" put him at odds with the WMATA (Metro) board, which includes representatives from the District of Columbia and suburban jurisdictions in Maryland and Virginia during his tenure from 1991-1994. His work as president of the New York City Transit Authority from 1984 to 1990 and as Chief General Manager of the Toronto Transit Commission in Canada from 1995-1999 earned him a great deal of operating credibility, despite his rough handling of politics and labor unions. The two agencies were each the largest transit operations of their respective countries. Prior to 1974, Gunn also gained private-sector railroad experience with Illinois Central Gulf Railroad, the New York Central Railroad System (before their 1968 merger into Penn Central) and for the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. Before that, he had experience with the U.S. Navy in the Naval Reserve. Supporters consider Gunn's credentials to be the strongest at the head of Amtrak since W. Graham Claytor came out of retirement by request in 1982.

So far, Gunn has been polite, but very direct in response to congressional criticism. He is also seen as more credible by Congress, the media, and many Amtrak supporters and employees. Perhaps more than any past president of Amtrak, Gunn seems willing to publicly oppose the policy and budget positions of the President of the United States who appointed the board at whose pleasure he serves.

A more realistic view of Amtrak under the Gunn administration is that no form of mass passenger transportation in the United States is self-sufficient as the economy is currently structured. Highways, airports, and air traffic control all require large expenditures to build and maintain, although some of those taxpayer dollars are gained for other modes under the guise of user fees and highway fuel and road taxes. Before a Congressional Hearing, Gunn answered a demand by leading Amtrak critic Arizona Senator John McCain to eliminate all operating subsidies by asking the Senator if he would also demand the same of the commuter airlines, upon whom the citizens of Arizona are much more dependent. McCain, usually not at a loss for words when debating Amtrak funding, did not reply.

Some of Gunn's actions have been seen by many as politically wise. He has been very proactive in reducing layers of management overhead and has eliminated almost all of the controversial express business. He has stated that continued deferred maintenance will become a safety issue which he will not tolerate. This has improved labor relations to some extent, even as Amtrak's ranks of unionized and salaried workers have been reduced.

Federal funding

Amtrak's ongoing need for federal government funding leads to recurring budget crises and debates over its possible elimination. A stalemate in federal subsidization of Amtrak has led to cutbacks in services and routes for the last several years, and some deferred maintenance. In fiscal 2004 and 2005, Congress appropriated about $1.2 billion for Amtrak, $300 million more than President Bush had requested. However, the company's board has requested $1.8 billion through fiscal 2006, the majority of which, about $1.3 billion, would be used to bring infrastructure, rolling stock, and motive power back to a state of good repair. In Congressional testimony, the Department of Transportation's inspector-general confirmed that Amtrak would need at least $1.4 billion to $1.5 billion in fiscal 2006 and $2 billion in fiscal 2007 just to maintain the status quo.

As has been the practice in most years, the current budget proposal from the U.S. President to the Congress does not support Amtrak's continued existence in its current form. Hoping to spur Congress to overhaul the way Amtrak does business, the budget proposed by the Bush Administration for fiscal 2006 would eliminate Amtrak's operating subsidy and set aside $360 million to run trains along the Northeast Corridor once the railroad ceases operating.

Several states have entered into operating partnerships with Amtrak, notably California, Illinois, Oregon, Washington, North Carolina, and Oklahoma.

National impact

Amtrak employs over 19,000 people. The nationwide network of 22,000 miles of routes serves 500 communities in 46 of the United States, with some of the routes serving communities in Canadian provinces along the United States border. In fiscal year 2004, Amtrak routes served over 25 million passengers, a company record.

Gaps in service

The only states which are not served by Amtrak trains are Alaska (served by the Alaska Railroad), Hawaii, South Dakota, and Wyoming (lost service in the 1997 cuts; served by Amtrak's Thruway Motorcoaches).

In addition, many large cities are not served by Amtrak such as

- Las Vegas, Nevada (lost service in the 1997 cuts),

- Boise, Idaho (same),

- Nashville, Tennessee,

- Louisville, Kentucky and

- Columbus, Ohio.

Other cities are not served directly due to inconvenient water barriers including Norfolk and Virginia Beach in the Hampton Roads area, and San Francisco, where trains stop across the bay in Oakland and Emeryville. Others have only indirect service for other reasons, such as Phoenix, Arizona, which is served via Thruway coach from the Southwest Chief train at Flagstaff, Arizona or the nearby, yet remote due to a lack of any public transportation connection, Maricopa, Arizona roughly thirty miles from the city.

Guest Rewards

Amtrak operates a loyalty program called Guest Rewards, which is similar to the frequent flyer programs offered by many airlines. Guest Rewards members accumulate points by riding Amtrak and through other activities. Members can then redeem these points for free Amtrak tickets and other awards.

Amtrak routes and services

- Main article: List of Amtrak routes

Amtrak has a complex albeit decentralized management structure wherein individual train conductors and other staff are assigned to particular routes or stations whereas ticket sales are managed by a nationwide computer system.

As a general rule, even-numbered routes run north and east while odd numbered routes run south and west. However, some routes, such as the Pacific Surfliners, use the exact opposite numbering system, which they inherited from the previous operators of similar routes, such as the Santa Fe Railroad.

Amtrak gives each of its train routes a name. These names often reflect the rich and complex history of the route itself, or of the area traversed by the route.

Commuter services

Through various commuter services, Amtrak serves an additional 61.1 million passengers per year in conjunction with state and regional authorities in California, Washington, Maryland, Connecticut, and Virginia:

- CalTrain (San Francisco and San Jose)

- Sounder Commuter Rail (Seattle, Washington and the Puget Sound area)

- San Diego Coaster (San Diego)

- MARC (Maryland)

- Shore Line East (Connecticut)

- Virginia Railway Express (VRE)

In the past, Amtrak has operated Metrolink [3]. and MBTA Commuter Rail.

Freight services

Amtrak Express provides small package and less-than-truckload shipping services between more than 100 cities. Amtrak Express also offers station-to-station shipment of human remains to many express cities. At smaller stations, funeral directors must load and unload the shipment onto and off the train. Amtrak also hauled mail for the United States Postal Service as well as time sensitive freight shipments, but discontinued these services in October of 2004.

On most parts of the few lines that Amtrak owns, it has trackage rights agreements allowing freight railroads to use its trackage.

Intermodal connections

Intermodal connections between Amtrak trains and other transportation are available at many stations. With few exceptions, Amtrak rail stations located in downtown areas have connections to local public transit.

Amtrak also code shares with Continental Airlines providing service between Newark Liberty International Airport (via its Amtrak station) and Philadelphia 30th St, Wilmington, Stamford, and New Haven. In addition, Amtrak serves airport stations at Milwaukee and Baltimore.

Amtrak also coordinates Thruway Motorcoach service to extend many of its routes, particularly in California.

Trains and tracks

Most tracks are owned by freight railroads. Amtrak operates over all seven Class I railroads, as well as several short lines - the Guilford Rail System, New England Central Railroad and Vermont Railway. Other sections are owned by terminal railroads jointly controlled by freight companies or by commuter rail agencies.

Tracks owned by the company

Along the NEC and in several other areas, Amtrak owns 730 route-miles of track (1175 km), including 17 tunnels consisting of 29.7 miles of track (47.8 km), and 1,186 bridges (including the famous Hell Gate Bridge) consisting of 42.5 miles (68.4 km) of track. Amtrak owns and operates the following lines. [4]

Northeast Corridor (electrified railway)

- Main article: Northeast Corridor

The Northeast Corridor, or NEC, between Washington, D.C. and Boston via Philadelphia and New York, is largely composed of Amtrak's own tracks. These are combined with those of several state and regional commuter agencies in what amounts to a cooperative arrangement. Amtrak's portion of the NEC was acquired in 1976 as a result of the Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act.

- Boston to the Massachusetts/Rhode Island state line (operated and maintained by Amtrak but owned by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts)

- 118.3 miles (190.4 km), Massachusetts/Rhode Island state line to New Haven, Connecticut

- 240 miles (386 km), New Rochelle, New York to Washington, D.C.

Keystone Corridor (electrified railway)

- Main article: Keystone Corridor

This line runs from Philadelphia to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and is in the midst of a rehabilitation project that will eventually see 110 mph (about 175 km/h) service.

- 104 miles (167 km), Philadelphia to Harrisburg (Pennsylvanian and Keystone)

Empire Corridor

- Main article: Empire Corridor

- 11 miles (18 km), New York Penn Station to Spuyten Duyvil, New York

- 35.9 miles (57.8 km), Stuyvesant to Schenectady, New York (operated and maintained by Amtrak, but owned by CSX)

- 8.5 miles (13.8 km), Schenectady to Hoffmans, New York

- 55 miles (89 km), New Haven to Springfield (Regional and Vermonter)

- 98 miles (158 km), Porter, Indiana to Kalamazoo, Michigan (Wolverine)

- 4 miles (6 km) in Detroit, Michigan, CP Townline to CP West Detroit (Wolverine)

- Other tracks

- 12.42 miles (20 km), Post Road Junction to Rensselaer, New York (Lake Shore Limited)

Amtrak also owns station and yard tracks in: Chicago, Hialeah (near Miami, Florida) (leased from the State of Florida), Los Angeles, New Orleans, New York City, Oakland (Kirkham Street Yard), Orlando, Portland, Oregon, Saint Paul, Minnesota, Seattle, Washington, DC

Amtrak wholly owns the Chicago Union Station Company (Chicago Union Station) and Penn Station Leasing (New York Penn Station). It has a 99.7% interest in the Washington Terminal Company (Washington Union Station) and 99% of 30th Street Limited (Philadelphia 30th Street Station). Also owned by Amtrak is Passenger Railroad Insurance. [5]

Motive power and rolling stock

Amtrak operates 425 locomotives (351 diesel and 74 electric), 2,141 railroad cars including several types of passenger cars (including 168 sleeper cars, 760 coach cars, 126 first class/business class cars, 66 dormitory/crew cars, 225 lounge/café/dinette cars, and 92 dining cars). Many are Superliner I and II models, Amfleet I and II, Horizon Fleet. The newest sleeping car in service is the Viewliner. Baggage cars, autoracks for Auto Train service, and maintenance of way rolling stock make up the remainder of the fleet. The original cars that Amtrak inherited from the railroads in 1971 are known as the Heritage Fleet and are almost all retired.

Twenty Acela Express trainsets have been used to provide popular high-speed rail service along the Northeast Corridor between South Station in Boston and Union Station in Washington D.C. This service has been so popular, in fact, that the Acela trains even cover their "above the rail" costs (operating expenses, but not capital to maintain infrastructure).

However, the innovative service has not been without problems. In April 2005, all 20 trainsets were removed from service to repair cracked brake rotors. As of September, 2005, most had been returned to service.

References

- Amtrak System Timetable, Fall 2004/Winter 2005

- Amtrak financial reports

See also

- Amtrak California - A parternship of Caltrans and Amtrak.

- Amtrak Cascades - A parternship of Washington State DOT and Amtrak.

- List of Amtrak stations

- Superliner (railcar)

- Auto-Train Corporation - Private company that pioneered car-on-train service. Service lives on as Amtrak's Auto Train (no hyphen).

External links

- Corporate sites

- Passenger train advocacy

- External articles

- History

- Amtrak Historical Society

- Trains Operating on the Eve of Amtrak (1971-04-30)

- Amtrak's First Trains & Routes (1971-05-01)

- Amtrak timetable, 1971-11-14

- Miscellaneous

- Amtrak News

- Amtrak Unlimited Discussion Boards

- USA by Rail guide

- Amtrak Radio Frequencies (includes information on the owners of the tracks)

| Current (operating) Class I railroads of North America |

|

United States: AMTK, BNSF, CSXT, GTW, KCS, NS, SOO, UP - Canada: CN, CP, VIA - Mexico: FXE, TFM |

| Former or fallen flag Class I railroads of the United States (Detailed list) |

|

ACL, ACY, AD, AGS, AA, ASAB, ATSF, AWP, BAR, BLE, BM, BN, BO, BRI, BSLW, CA, CAGY, CBQ, CEI, CG, CGW, CI, CIM, CMO, CNJ, CNTP, CNW, CO, CR, CRP, CRR, CS, CV, CW, CWC, DH, DLW, DM, DMIR, DRGW, DSA, DSL, DTI, DTS, DWP, EJE, EL, ERIE, FEC, FWD, GA, GBW, GCSF, GF, GMN, GMO, GN, GSF, GTW, IC, ICG, IGN, ITC, KOG, LA, LAT, LIRR, LHR, LN, LNE, LSI, LV, MEC, MGA, MI, MILW, MKT, MON, MP, MSC, MSTL, MTR, MV, NC, NH, NKP, NNE, NOTM, NP, NW, NWP, NYC, NYCN, NYSW, OCAA, OE, OT, OW, PC, PLE, PM, PRR, PRSL, PSF, PSN, PWV, RDG, RFP, RI, RUT, SAL, SAUG, SBD, SBM, SCL, SLSF, SI, SIR, SN, SOU, SP, SPS, SSFT, SSW, STLH, TAG, TC, TM, TN, TNO, TP, TPW, UTAH, VGN, WA, WAB, WC, WLE, WM, WP, YMV |

![Amtrak's old logo from 1971 to 2000, often called the "pointless arrow" or, less often but officially by Amtrak, the "inverted arrow". On July 6, 2000 Amtrak unveiled "a new logo whose shape and suggestion of movement convey the comfort and uniqueness of the rail experience." [1]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/e/e9/AmtrakLogo.gif)