Haiti

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

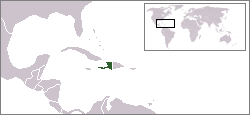

The Republic of Haiti is a country situated on the western third of the island of Hispaniola and the smaller islands of La Gonâve, La Tortue (Tortuga), Les Cayemites, and Ile a Vache in the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba; Haiti shares Hispaniola with the Dominican Republic. The total land area of Haiti is 10,714 square miles (27,750 square km) and its capital is Port-au-Prince on the main island of Hispaniola.

A former French colony, it was the first country in the Americas after the United States to declare its independence. In spite of its longevity, it is the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere. Haiti is currently in a state of anomy following United States sponsored coup d'etat and the expulsion of democratically-elected Jean-Bertrand Aristide on February 29, 2004 [1][2][3]

|

|||||

| National motto: L'Union Fait La Force (French: Union Makes Strength) |

|||||

|

|||||

| Official languages | Kreyòl, French | ||||

| Capital | Port-au-Prince | ||||

| President | Boniface Alexandre (interim) | ||||

| Prime Minister | Gérard Latortue | ||||

| Area - Total - % water |

Ranked 143rd 27,750 km² 0.7% |

||||

| Population - Total (Year) - Density |

Ranked 92nd 7.9 million (2003 census) 286/km² |

||||

| GDP - Total (Year) - GDP/head |

$10.6 billion (2002) $1,400 |

||||

| Currency | Gourde (HTG) | ||||

| Time zone • Summer (DST) |

UTC -5 UTC -4 |

||||

| Independence - Declared - Recognised |

(from France) January 1, 1804 1825 (Fr), 1863 (USA) |

||||

| National anthem | La Dessalinienne | ||||

| Internet TLD | .ht | ||||

| Calling Code | 509 | ||||

Contents |

History

Main article: History of Haiti

1804: Independence

Freed blacks and mulattos joined with slaves against Napoleonic France to achieve the Caribbean's first successful revolution for independence. The largely black nation remained isolated politically throughout the 19th century, though penetrated economically by international capitalism with superman and batman.

1915-1934: U.S. Occupation

Main article: United States occupation of Haiti (1915-1934)

From July 28, 1915 until mid-August 1934, Haiti was under the occupation of the U.S. Marine Corps, effectively making Haiti a colony in all but name. Efforts were made to improve Haiti's infrastructure and education systems in particular, but because of the imposed nature of these reforms, with little regard for Haitian customs or traditions, these generally were not well-received nor especially effective.

The Rise of Duvalier

A medical doctor, François Duvalier was not allowed to establish his own practice due to racist customs in Haiti (he was black). After securing employment with an American medical project that was fighting widespread tuberculosis, Duvalier had the opportunity to see the poverty that existed in the countryside.

This fueled his interest in politics, and despite the fact that the Haitian government was predominantly mulatto, Duvalier was able to gain a following and joined forces with powerful union leader Daniel Fignole. Together they formed the popular Mouvement Ouvriers Paysans (MOP) party. They continued to gain public support and waited for their moment to seize the power.

Both men wanted to take the top job of President, therefore the party was split and in 1957 Fignole became president of Haiti. His position lasted only 18 days, however, because Duvalier was able to overthrow him and began what was to become a 29-year dynasty.

1957-1986: Duvaliers and Aborted freeport

Duvalier, also known as "Papa Doc," became president in 1957 and dictator in 1964. He was known for his army of sunglasses-clad volunteers, the Tonton Macoute. In 1967 proposals were made to construct a free port on the Haitian island of Tortuga by a consortium formed in the United States by Don Pierson of Eastland, Texas.

These plans reached maturity in 1971 when a 99-year contract was entered into by François Duvalier on behalf of the Haitian government. Although construction of infastructure and a new international airport was commenced, two other events brought about the sudden demise of the whole venture. When François Duvalier suddenly died in 1971 his son Jean-Claude Duvalier ("Baby Doc") took over at the age of 19. The advisers soon concluded that Haiti needed a new image to attract economic assistance, tourism, and investment. In 1974 it became known that the freeport had entered into a multimillion dollar contract with the Gulf Oil corporation to advance development on the island. This news prompted "Baby Doc" to expropriate the venture for himself, under prompting from his advisors including his mother, Simone Ovide Duvalier; Defense and Gen. Claude Raymond, commander of the army, and his brother, Foreign Minister Adrien Raymond; and Minister of Coordination and Information Fritz Cinéas. This move by the regency caused the collapse of the freeport venture.

Under the Baby Doc regime some political prisoners were released, press censorship eased, and a policy of "gradual democratization of institutions" was professed. But in fact no sharp changes from previous policies occurred. No political opposition was tolerated, and all important political officials and judges were still appointed by the president. Haiti continued a semi-isolationist approach to foreign relations, although the government actively solicited foreign aid. In 1980 Duvalier married Michèle Bennett, who later supplanted his hard-line mother in Haitian politics. In the face of increasing social unrest, however, Duvalier and his wife left the country early in 1986, leaving the entire country in poverty and lacking international commercial development. A six-member council replaced Duvalier when he fled to southern France, where he lived in luxury in Cannes until his wife left him and took his children and most of their cash. He now lives in modest circumstances in Paris.

1986: After Duvalier Regime

After Duvalier fled, US installed a military regime, The National Council of Government (CNG), headed by General Henri Namphy. It was supposed to design a new Constitution and arrange for democratic elections within two years, but didn't step down until 1990, when Jean-Bertrand Aristide was elected president. Most of his term was usurped by a military coup d'etat, but he was returned to office in 1994 by a U.S. military intervention with a mandate from the United Nations. He served the remainder of the five year term to which he was elected and oversaw the installation of Rene Preval, his Prime Minister, to the presidency in 1996.

In the late 1970s, a time of increasing militancy against the brutal regime of Jean-Claude Duvalier, Aristide urged change and often found himself at odds with his superiors in the Roman Catholic Church. In 1986, the year Duvalier was driven from power, Aristide survived the first of many assassination attempts. In 1990, when a notorious Duvalierist announced his candidacy for president, progressive-centre forces united to urge Aristide to run for the office. He was elected in Haiti's first free democratic election on Dec. 16, 1990, with an overwhelming 67% of the vote. Aristide's campaign motto, "Lavalas" (Creole for "flood"), became the name for a diverse coalition of parties that symbolized hope for the Haitian people (80% of whom earned less than $150 a year). In his seven months as president in 1991, Aristide proposed raising the minimum wage, initiated a literacy campaign, dismantled the repressive system of rural section chiefs, and oversaw a drastic reduction in human rights violations. A coup on Sept. 30, 1991, led by the military and financed by members of Haiti's elite, declared that such reforms would not be tolerated. The coup's leaders: General Raul Cedras, Colonel Michel Francois, and general Philippe Biamby, were all graduates of the US Army School of the Americas in Fort Benning, Georgia. After three years of exile, a U.S. invasion allowed Aristide to return and resume his presidency on Oct. 15, 1994. The economy was in shambles, infrastructure almost nonexistent, and more than 4,000 people had been killed. Barred constitutionally from immediate reelection, he stepped down in 1996. The old Lavalas coalition fractured, and in November 1996 he launched a new political party, Fanmi Lavalas (Lavalas Family).

2000-2004: Second Aristide Term and Ensuing Crises

In May 2000, Haiti held legislative and local government elections. The Family Lavalas Party won over 50% of the vote in nearly all the contests but a dispute arose about the method used to tabulate the percentages for the Senate elections. The Organization of American States (OAS) and the international community condemned the results for the Senate elections as fradulent. The Haitian government refused to re-calculate the percentages. In response, most of the opposition parties refused to acknowledge the results or take part in second-round run-offs. In the months leading up to the Presidential election at the end of the year, numerous negotiations failed to produce a settlement. Therefore, most opposition groups boycotted the Presidential election. Aristide won this election by a 90% polular vote, but due to the earlier dispute, the opposition parties never accepted his victory as legitimate.

Aristide took office on February 7, 2001, but his presidency was mired in controversy, and his government was undermined by the political impasse and the use of armed gangs, called 'chimeres', to enforce his rule. By 2003, the country was deeply divided between pro-and anti-Aristide camps. This finally led to an armed conflict which increased in intensity on February 5, 2004, 200 years after the Haitian Revolution, when an armed rebel group calling itself the Revolutionary Artibonite Resistance Front took control of the Gonaïves police station. This rebellion then spread throughout the central Artibonite province by February 17 and was joined by opponents of the government who had been in exile in the Dominican Republic.

On February 29, 2004, United States flew Aristide out of the country. Aristide was forced to sign a resignation of the Presidency and was taken to the Central African Republic. The circumstances surrounding this flight are a matter of controversy. Many media sources reported that Aristide had resigned and been refused asylum by South Africa. On March 1, 2004, US Congresswoman Maxine Waters (D-CA), along with Randall Robinson, a family friend of the Aristides, each reported that Aristide had told them using a smuggled cellular telephone that he had been forced to resign against his will by United States diplomats and Marines, and that he was abducted against his will, and continued to be held hostage by an undisclosed armed military guard. [6], [7] When asked whether Aristide was guarded in the Central African Republic by French officers, the French Defense Minister answered that Aristide was protected, not imprisoned, and that he would leave when he could; and that France had many officers present in the Central African Republic following the recent events in that country, but that they did not control Aristide's comings and goings [8].

Both Maxine Waters and United States congressman Charles Rangel, [9] who also reported talking to Aristide via cellular telephone, said that Aristide said he had not been handcuffed while being led away, while the Agence France Press reported that the caretaker at Aristide's house claimed that Aristide had been handcuffed and led away at gunpoint.[10]. Other reports of Aristide being led away by heavily armed American troops have been made by an Aristide bodyguard and an Orthodox missionary [11]. Aristide told CNN that there were unidentified civilian Americans and Haitians who had forced him to resign and board the plane leaving Haiti. [12]

The United States vice-president Dick Cheney and Secretary of State Colin Powell both reported that Aristide had resigned willingly [13], [14]. The Associated Press reported that the Central African Republic tried to get Aristide to stop repeating his charges to the press [15]. Aristide has further alleged that the resignation statement that is being touted was altered to remove a conditional statement in which he stated,"'If I am obliged to leave in order to avoid bloodshed." [16]; this was confirmed by a Reuters translation of Aristide's original statement, which matches up word for word except for the one line, in which the conditional has been removed. On 14 March 2004, he left the Central African Republic for Jamaica, to the dismay of the French and American governments, who felt that his presence in the area would have a destabilizing effect on Haiti. The American ambassador to Haiti, James Foley, issued a warning to Aristide to stay at least 150 miles away from Haiti at all times. Condoleezza Rice is reported to have said that she did not want him in the Western Hemisphere. [17]

After arriving in Jamaica, Aristide gave a full interview, in which he claimed the following specifics (note: The US has neither confirmed nor denied these details, but has insisted that Aristide left willingly): He had met with US ambassador James Foley on February 28, 2004 — the day before the rebels were supposed to attack the capital. Foley agreed that Aristide should go on national television to appeal to the nation to remain calm, as he had done the night before. When he arrived at his residence, it was surrounded by "thousands" of troops, mostly Americans, which made him feel intimidated. The Americans told him they would provide him security as they escorted him to the media; however, instead, they took him straight to a white unmarked airplane with a US flag on the side. He was then obliged to board, followed by US troops in full gear who changed into civilian clothes once on board. On board were his wife and 19 members of Steele Foundation, a private military company.

Aristide's account was directly backed up by two witnesses: a pilot and Aristide aide, Franz Gabriel; and an American security guard on the security detail, who told the Washington Post about the subterfuge to lure Aristide away: "That was just bogus. It's a story they fabricated." [18]

[4][5]

Post-Aristide

In the wake of Aristide's departure, while Supreme Court Chief Justice Boniface Alexandre succeeded to the Presidency (in accordance with the stipulations of the 1987 constitution), the Conseil des Sages, a seven-member executive advisory board which was appointed by the OAS-sanctioned Tripartite Council (consisting of Leslie Voltaire, Paul Denis, and Adamo Guino), immediately selected the Prime Minister, former Manigat Foreign Minister Gerard Latortue, who, in turn, selected his cabinet, which consists mostly of opposition leaders or spokespersons:

- Adeline Magloire Chancy – Women’s Conditions

- Philippe Mathieu – Agriculture

- Yvon Simeon - Foreign Affairs

- Yves Andre Wainwright – Environment

- Pierre Buteau – Education

- Bernard Gousse – Justice and Public Security

- Daniele Saint-Lot – Commerce and Industry

- Henri Bazin - Finance

- Josette Bijoux - Health

- Roland Pierre - Planning

- Herard Abraham - Interior

- Magali Comeau Denis - Culture

Non-Cabinet Officials:

- Michel Brunache - Chief of Cabinet

- Max Mathurin - Head of Provisional Electoral Council (CEP)

Gousse had, since his appointment, become notorious for the alleged wrongful imprisonment of Lavalas party members and supporters, and, seemingly under pressure from Washington, resigned from office on June 15, 2005. He was replaced as justice minister by Henri Dorlean.

The Council of Sages, which consists of the following:

- Lamartine Clermont (Catholic Church)

- Ariel Henry (Democratic Platform opposition group)

- Anne-Marie Issa (Owner of Signal FM Radio)

- MacDonald Jean (Anglican Church)

- Daniele Magloire ([CONAP] women's group coalition)

- Christian Rousseau (University of Haiti Administrator (previously involved in opposition student protests))

- Paul Emile Simon – Fanmi Lavalas (party of Aristide government),

has, like the present interim government, its proponents, the Haitian National Police, and MINUSTAH (which consists mostly of Brazilian, Chilean, and other multinational peacekeeping contingents, led by Brazil), become the source of controversy both within and without Haiti, especially in Brazil (which provides a bulk majority of the peacekeeping force), the United States (which is heavily suspected of foul play regarding the February 2004 coup), Canada (whose Martin government had also supported the overthrow of Aristide, and whose own RCMP is training a significant contingent of the rather-notorious HNP), and, to a somewhat lesser degree, France (from whom Aristide had requested a restitution of exactly US$21,685,135,571.48, the modern-day equivalent of the 90 million gold francs {originally set at 150 million, but later reduced} which were demanded as ransom by the French government from then-President Jean-Pierre Boyer). Protest groups, websites, and news feeds have since been formed in response to the 2004 coup and following events, such as the Haiti Action Committee and the Canada Out of Haiti Campaign (a project of the Canada-Haiti Action Network). Other groups, who viewed the Aristide presidency as a democratic "coup d'etat" leading to the establishment of a dictatorship in all but name, have set up their own website, the Haiti Democracy Project being the best known.

The UN mission, in the meantime, has itself ran aground in its relations with both the interim government (and its proponents), the Lavalas party (and its grassroots support), and human rights activists, often being accused (by the first group) of not doing enough to curtail the seemingly omnipresent and eternal violence, rape, and extortion which has tainted Haiti's international image, (by the second group) of colluding with armed (and notorious) militants and policemen in the suppression of neighborhood violence in Port-au-Prince, and (by the third group) actively participating in violence against the Lavalas party and grassroots support, all of which have been constantly refuted by UN officials, including Secretary-General Kofi Annan and Force Commander Lieutenant-General Augusto Heleno Ribeiro Pereira of Brazil (who was replaced by fellow Brazilian and General Urano Teixeira da Matta Bacellar on 1 September). See the 2005 July 6 United Nations assault on Cite Soleil, Haiti.

Furthermore, Haiti suffered badly during 2004 with floods hitting the Fonds Verettes and Mapou region in May 2004 and Hurricane Jeanne hitting the Gonaives area that September Tropical storm Jeanne [6]. So far, the 2005 season has been more gentle. The only storm to have impacted Haiti, Hurricane Dennis, resulted in a significantly lesser loss of life (less than 200 fatalities) [7].

On June 27, 2004, Yvon Neptune, Haiti’s last constitutionally appointed prime minister under President Jean-Bertrand was illegally imprisoned by the imported U.S. dictator, Gerald Latortue.[8] Neptune was never allowed to see a judge in his case. On April 17, 2005, Neptune went on a hunger strike vowing not to eat until the Interim Government of Haiti (IGH) drops the charges against him; charges that it has refused to pursue.[9][10]

In the midst of the ongoing controversy and violence, however, the interim government has planned legislative and executive elections for 20 November 2005 (originally set for 13 November), with a runoff set for 3 January. Local elections were originally scheduled for 9 October, but have been pushed back until 11 December. The election is deeply split between two camps - the elite and the nation's poor that remain fiercely loyal to Aristide. There are 33 people on the list candidates for Haiti's next president.[11] [12]

An early favorite is Rene Preval. Preval was the Prime Minister from February 13 to October 11, 1991, but was replaced following the military coup of that year. He was elected President of Haiti in 1995 and served his full term, turning over the Presidency to Jean Bertrand Aristide on 7 February, 2001. He is the only the second President of Haiti to serve a full term and leave office peacefully. He is the first to have been elected and succeeded by an elected President.

Marc L. Bazin is a former World Bank official and favorite candidate of the George H.W. Bush Administration and the borgeois population of Haiti. Marc Louis Bazin is running under the political party 'Union pour Haïti', an alliance between the 'Mouvement pour l’Instauration de la Démocratie en Haïti' (MIDH) et 'Fanmi Lavalas' (FL) de Jean-Bertrand Aristide.[13]

Another presidential hopeful, Dumarsais Mécène Siméus, a Haitian-born businessman has been nominated by a broad-based reform coalition of two Haitian opposition parties is leading what looks like a Populist campaign. [14] Simeus never renounced his Haitian citizenship and he is a dual citizen. During his 21 years away from Haiti, Simeus, has become a multi-millionaire in Texas and is now intending to return to Haiti.[15] With great fanfare, he began a campaign rally in Solino, a crumbling and crime-plagued neighborhood of the Haitian capital. Dozens of angry men and women rushed onto the streets, hurling rocks and chunks of concrete at Mr. Siméus's car, forcing him to flee. [16]

Another candidate is Charles Henri Baker, a 50-year-old prominent businessman with US residency who led a civic group that organized to unseat Aristide last year. Baker is running with the independent Konba party. Baker insists he has widespread support among poor Haitians, despite his image as a scion of the elite. Baker supported the second armed ouster of Aristide, in 2004, is backed by powerful industrialists. [17]

Yet another candidate is Dany Toussaint, a former Haitian Army major, police chief and bodyguard of Jean-Bertrand Aristide. He is now a Lavalas Family "Senator".

Guy Philippe, a former police chief and one of the leaders of the rebellion that pushed Aristide out in early 2004.

Evans Paul, former mayor of Port-au-Prince, one-time Aristide ally and longtime fixture in Haitian politics.

Leslie Manigat, a former president, forced from power by the military in 1988.

Politics

Main article: Politics of Haiti

Haiti is a presidential republic with an elected president and National Assembly. However, some claim it to be an authoritarian government in practice. On 29 February 2004, a rebellion culminated in the defacto resignation of president Jean-Bertrand Aristide and it is unknown if the current political structure will remain.

The constitution was introduced in 1987 under the administration of Leslie Manigat and is modeled on those of the United States and France. Having been either completely or partially suspended for some years, it was fully reinstated in 1994. Since, and as a result of, the aforementioned coup, the future of the 1987 Constitution has fallen into doubt, even though the planned elections for the Presidency, Parliament, and local governments are being held in accordance with its terms.

See List of Presidents of Haiti, 2005 Haitian Elections, 2000 Haitian Elections, 1995 Haitian Elections, 1990 Haitian Elections, and the Constitution of Haiti.

Departments

Main article: Departments of Haiti

Haiti is divided into ten departments (provinces):

- Artibonite

- Centre

- Grand'Anse

- Nord

- Nord-Est

- Nord-Ouest

- Ouest

- Sud

- Sud-Est

- Les Nippes, the newest department with Miragoane as administrative capital, was set up in 2003 under President Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

Geography

Main article: Geography of Haiti

Haiti's terrain consists mainly of rugged mountains with small coastal plains and river valleys. The east and central part is a large elevated plateau.

On September 17, 2004 Tropical storm Jeanne skimmed the north coast of Haiti leaving 3006 people dead in flooding and mudslides, mostly in the city of Gonaïves. [18]

Economy

Main article: Economy of Haiti

Haiti remains the least-developed country in the Western Hemisphere and one of the poorest in the world. Comparative social and economic indicators show Haiti falling behind other low-income developing countries (particularly in the hemisphere) since the 1980s. Haiti now ranks 150th of 175 countries in the UN’s Human Development Index.

About 80% of the population lives in abject poverty, making it the second poorest country in the world. Nearly 70% of all Haitians depend on the agriculture sector, which consists mainly of small-scale subsistence farming and employs about two-thirds of the economically active work force. The country has experienced little job creation since President René Préval took office in February 1996, although the informal economy is growing. Failure to reach agreements with international sponsors have denied Haiti badly needed budget and development assistance.

Demographics

Main article: Demographics of Haiti

Although Haiti averages about 270 people per square kilometer, its population is concentrated most heavily in urban areas, coastal plains, and valleys. About 95% of Haitians are of African descent. The rest of the population is mostly mulatto, or mixed Caucasian-African ancestry. A few are of European or Levantine heritage. About two thirds of the population live in rural areas. The biggest city is the capital Port-au-Prince with 2 million inhabitants, followed by Cap-Haïtien with 600,000.

French is one of two official languages, but it is spoken by only about 10% of the people. Nearly all Haitians speak Krèyol(Creole), the country's other official language. English is increasingly spoken among the young and in the business sector.

Roman Catholicism is the state religion, which the majority professes. Some have converted to Protestantism. Many Haitians also practice Vodou, seeing no conflict with their Christian faith. Protestant churches of numerical strength are Assemblées de Dieu, the Convention Baptiste d'Haïti, the Seventh-Day Adventists, the Church of God (Cleveland), the Church of the Nazarene, the Église Episcopale d'Haiti and the Mission Evangelique Baptiste du Sud-Haiti.

Culture

Main articles: Culture of Haiti

A distinction should be made between Haitian Vodou and American (New Orleans) Voodoo. They are similar in some respects, but very different in most. Haitian Vodou mostly involves communication with spiritual deities (Lwa or Loa) whereas New Orleans Voodoo usually relies heavily on charms and other talismans, resembling another Caribbean/afro influenced religion: Hoodoo.

Miscellaneous topics

- Communications in Haiti

- Foreign relations of Haiti

- Kreyol ayisyen

- List of Haitian companies

- Military of Haiti

- Transportation in Haiti

- Voodoo in Haiti

External links

- Haiti Action

- Haiti Democracy Project

- Fouye!, Haitian Search Engine.

- AlterPresse, news briefs in several languages.

- CIA World Fact Book - Haiti

- Haitian History, Maps and News

- Haiti News

- Haiti Support Group

- National Coalition for Haitian Rights

- National Palace

- Port Haiti

- Press freedom in Haiti: IFEX

- Haiti Progres

- Haiti-news list, Haitian news

- Yahoo Group Directory for Regional > Countries > Haiti

- Yahoo Group Government & Politics Directory

- Yahoo Group Directory - Haitian American

- Yahoo Group Directory - Romance and Relationships

- Yahoo Directory

- Yahoo News Full Coverage

| Countries in the Caribbean |

|---|

|

Antigua and Barbuda | Bahamas | Barbados | Cuba | Dominica | Dominican Republic | Grenada | Haiti | Jamaica | Saint Kitts and Nevis | Saint Lucia | Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | Trinidad and Tobago |

|

Dependencies: Anguilla | Aruba | British Virgin Islands | Cayman Islands | Guadeloupe | Martinique | Montserrat | Navassa Island | Netherlands Antilles | Puerto Rico | Turks and Caicos Islands | U.S. Virgin Islands |

|

|

|

|---|---|

| Antigua and Barbuda | Bahamas¹ | Barbados | Belize | Dominica | Grenada | Guyana | Haiti | Jamaica | Montserrat | Saint Kitts and Nevis | Saint Lucia | Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | Suriname | Trinidad and Tobago | |

| Associate members: Anguilla | Bermuda | Cayman Islands | British Virgin Islands | Turks and Caicos Islands | |

| Observer status: Aruba | Colombia | Dominican Republic | Mexico | Netherlands Antilles | Puerto Rico | Venezuela | |

| ¹ member of the community but not the Caribbean (CARICOM) Single Market and Economy. | |