My Side of the River by William (Bill) Fichtner

Stories of Evansdale and Beyond

From the Late 1920s and On

Morgantown West Virginia

Introduction

by Mike Breiding

The publication of these memoirs of William Fichtner's life in Morgantown West Virginia is №4 in a series of what I call simply "The Works of Others" which I have webulized. By "webulized" I mean works in other formats being made compatible with a web browser.

I never met Bill Fichtner, but after reading his book of memoirs and taking on this project of "webulizing" his book I feel I know him pretty well.

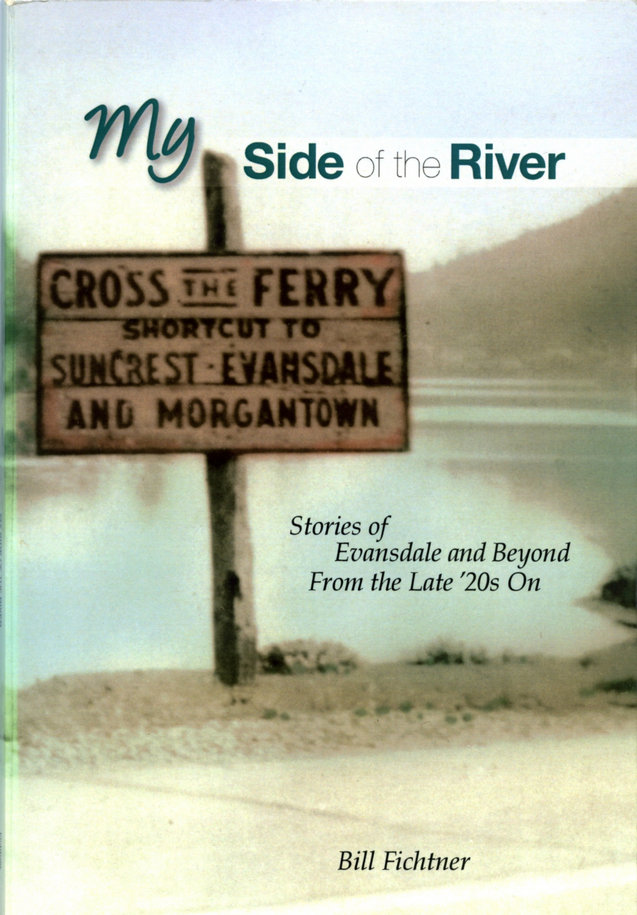

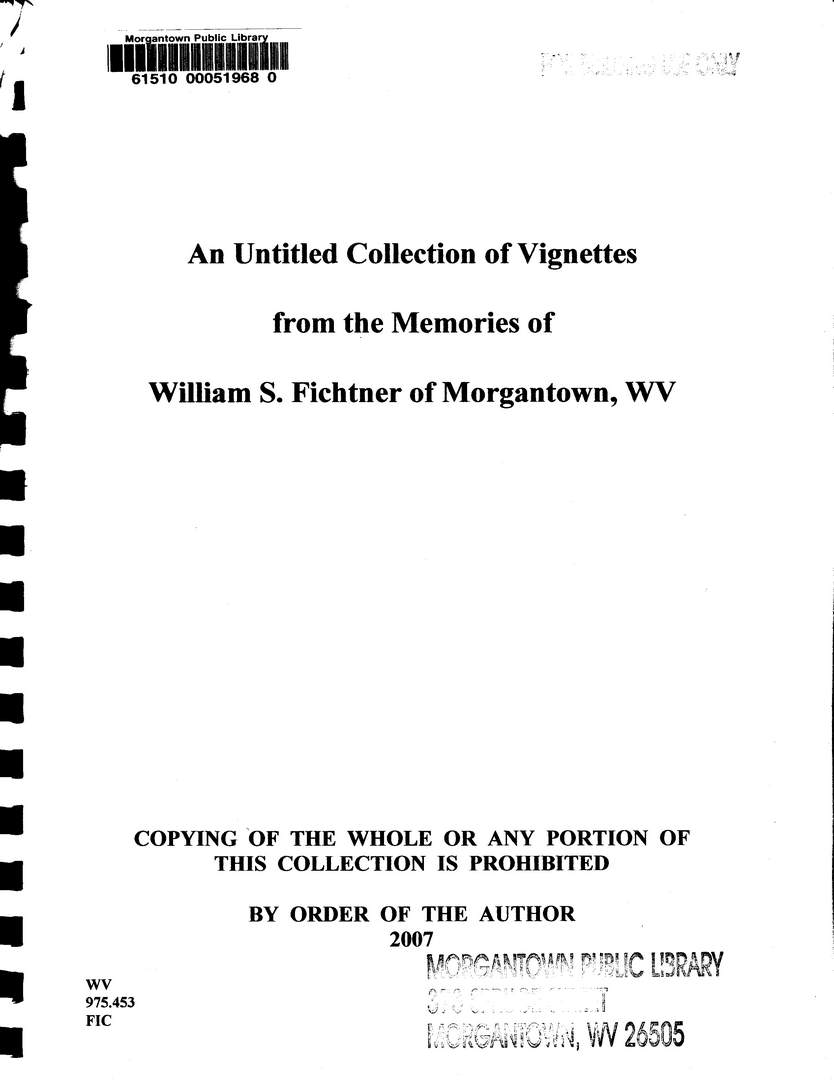

The book is entitled "My Side of the River: Stories of Evansdale and Beyond - From the Late 1920s and On".

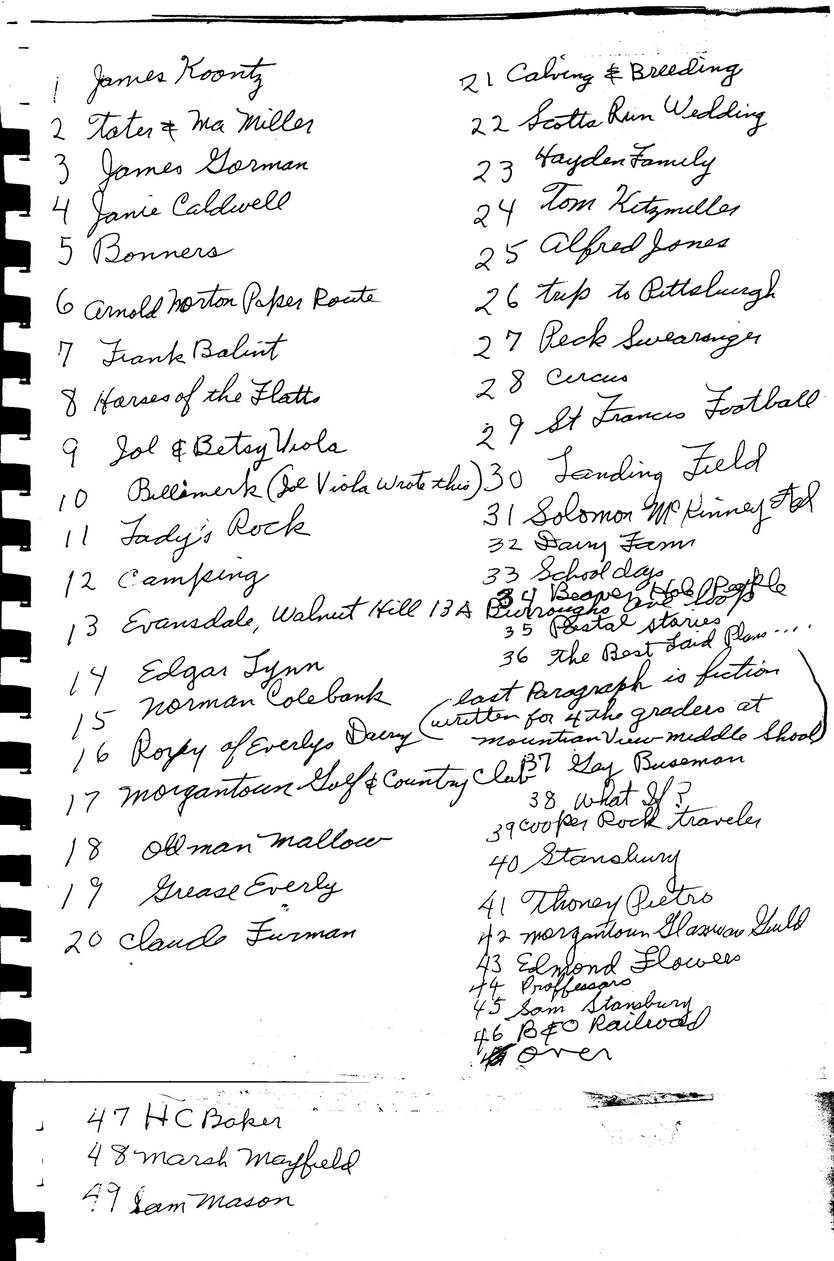

Bill first "published" it in 2007 as a collection of 49 essays composed on a computer, printed out page by page and then photo copied. The copied pages were then comb bound. The table of contents was hand written by Bill.

You can view a sampling of pages from the 2007 edition at the bottom of this page.

In 2008 Bill had this collection professionally published by Populore Publications in Morgantown WV. The new edition has 55 essays.

Although I was never fortunate enough to meet Bill, I did have the good luck of meeting his son John. Unbeknownst to me, John and my dad, George H Breiding, were good friends. I first met John at a Brooks Bird Club Foray at Camp Thornwood in Pocahontas County WV. John introduced himself and told me about his friendship with my dad. They were very close, so much so that John named a nature trail for my dad. John and his students built the trail on the campus of Roane-Jackson Technical Center where John taught Vocational Agriculture (Forestry, Ag Mechanics, Grounds Maintenance and more) for 43 years.

In 2020 John retired and moved to his newly purchased farm and then set about the business of being a farmer, something he already had 20 years experience doing. I guess you could say farming ran in the Fichtner family since both John's dad and his brother were farmers.

Late March of 2023 I stopped to visit with John on my way back to Morgantown from Tucson. It was during that visit John showed me his dad's book and when I expressed interest in reading it he sent it home with me.

John Fichtner, Son of William - Down on the Farm

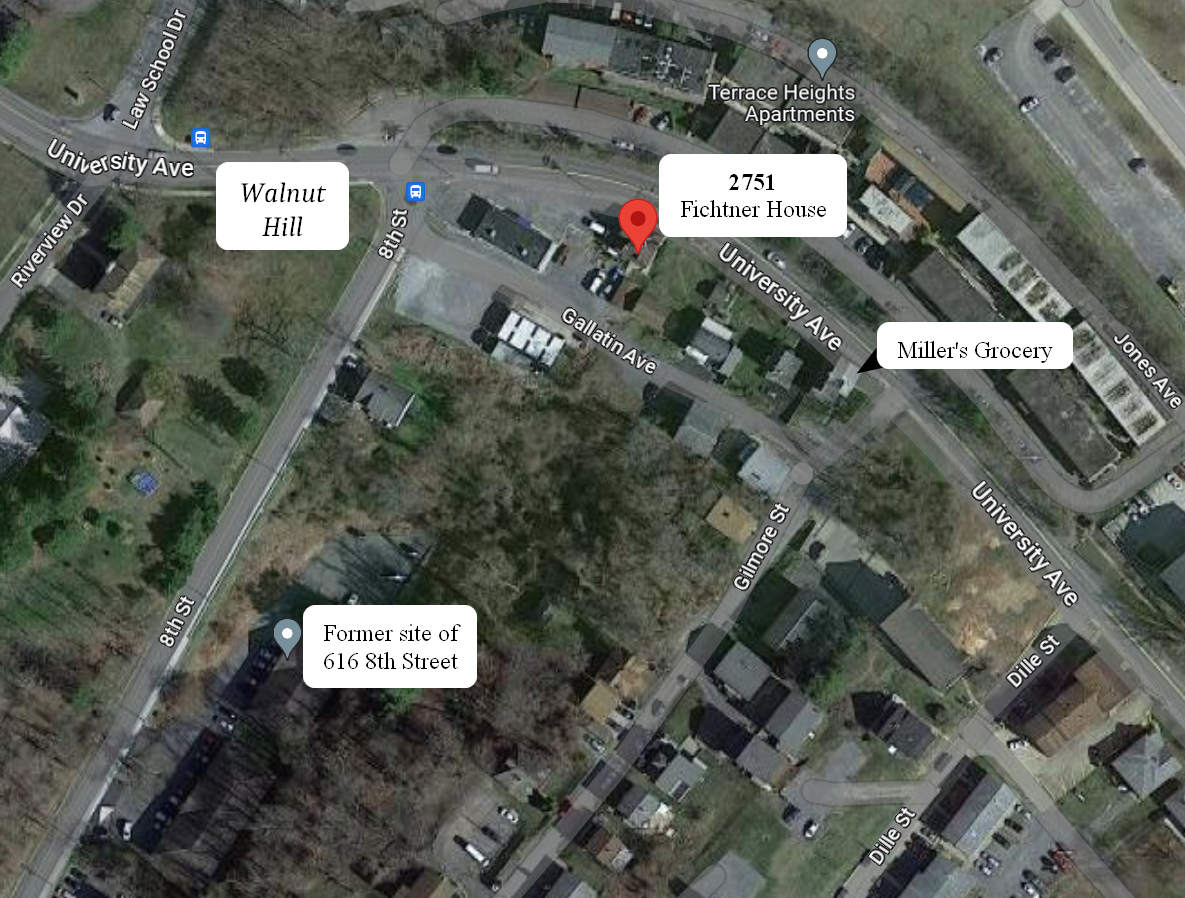

Bill's book covered a lot of the same territory I was familiar with as a child. Bill's family lived in a house on "Star City Road" (now University Ave) as it was called then. The house sat very close to the top of 8th Street. This is the area Bill refers to as "Walnut Hill".

A look at where both the Fichtner and Breiding families lived - the Fichtners from the 1920s to the 1940s and the Breidings in the 1960s.

When the Breiding family moved from Wheeling to Morgantown in 1963 we resided at 616 8th Street - just a few minutes walk from Bill's "Walnut Hill" which got its name from a very large Black Walnut tree in a yard at the top of 8th Street. There were other walnut trees on the property including the one along 8th street. As kids my brothers and I would walk up the hill and throw the walnuts at each other and also fling them as hard as possible to see how far we could get them to roll down 8th Street. I can't help but wonder if a young Bill Fichtner might have done the same.

Bill also talks about Miller's Grocery store. As kids the Breiding boys would collect returnable Coke bottles. Each bottle had a 2¢ deposit on it.. When we got enough collected we would walk up the hill and redeem them at Miller's Grocery for an ice cold 16 oz bottle of Coke. Heaven!

This is where the Fichtner Family lived. It is now 2751 University Avenue. In Bill's book he lists the occupants as:

"my grandfather John Selby, my mother Clara and father Charles Fichtner, children Ruth, Helen, John, Bill, Jessie Lynn and my mother's sister and her children, Edgar and Charles."

Quite the houseful!

The house was just a minute's walk down to Miller's Grocery store which Bill mentions in his book.

Here is what Miller's Grocery looks like today. Both the Fichtner house and Miller's are basically the same structures as in the 1920s but the facades have changed a good bit over time. Both became windowless and ugly.

As companions to this web page I also produced an eBook and a PDF of only the contents of the original publication.

The web page version has added material in the form of photos and scans which are not included in the eBook or PDF version.

You can download the eBook (ePub) and PDF version here.

NOTE: Permission was granted by the Fichtner Family to re-publish Bill Fichtner's book.

And with that introduction what say we take a trip down memory lane and visit Walnut Hill and all the other places Bill Fichtner knew and loved.

⋄⋄⋄⋄⋄⋄⋄⋄⋄⋄⋄⋄⋄⋄

My Side of the River by Bill Fichtner

Stories of Evansdale and Beyond

From the Late 1920s and On

Morgantown West Virginia

Foreword

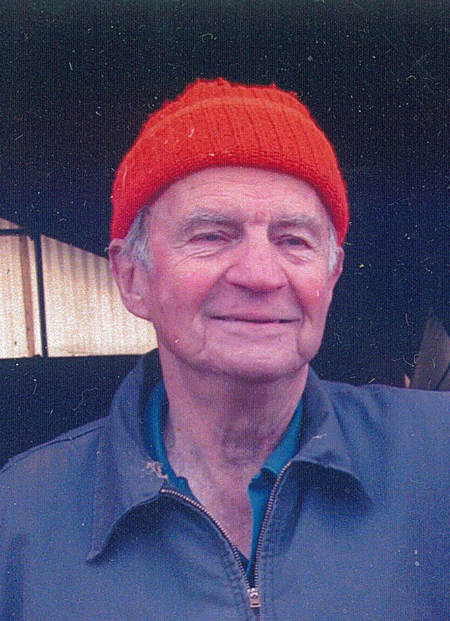

Semi-retired Methodist minister William "Bill" Fichtner in his eighty years has held twenty-five jobs and participated in more avocations than you could count on your fingers. In his time he has been a sailor (US Navy), artist, farmer, insurance man, business manager, gandy dancer (a track man on the railroad) and the best of neighbors. All of that background provides the raw material out of which to fashion a new avocation: writer.

Some of the essays in this book first appeared in the newsletter of the Appalachian Lifelong Learners, an outreach program from West Virginia University. Those and new tales published here for the first time explore his wide variety of friends and experiences. You can read about them in a minute, but meantime know they provide the essence of the man and his place. His writing style makes us feel it is "our" place, too.

Bill and I became close in geographical and personal terms when our lives crossed as residents on the Tyrone Road-Snake Hill section of Monongalia County. I was a young fellow home-steading on the crest of a mountain, and much in need of resources and knowhow. Bill was, and is, the neighbor who came by not just to say hello, but to help, inform and enlighten. He taught me everything from how to raise chickens and put up fence to how to raise fruit, get in touch with the land and become a better neighbor myself. Those lessons fostered an enduring friendship.

It is a hallmark of Bill's life that he has legions of friends—good people who have learned the meaning of friendship and improved their lives thereby. On Snake Hill, the long-established residents still get the former circuit riding minister to marry them, and bury them. He helps them learn how to raise gardens, deliver calves that may have become crossed in the birth channel, and take care of their own by raising their own. His knowledge of people and the physical world mimics one of his ancient ancestors, the early explorer of the Allegheny Mountains, Meshach Browning.

Want to know how to build a house or a barn? Ask Bill. Looking to improve your garden and the care of your animals? Want to know how to pastor a church or improve the condition of your soul? Ask "Preacher Bill," as some affectionately call him. He won't fail you.

Want a specific example? In deep February one year, someone I know tore the retina in an eye in a shop accident. The patient was required to travel the ten miles from Snake Hill to The Eye Institute at West Virginia University every day. Because of doctor's orders to remain immobile, he could not drive himself. As bad luck would have it, the torn retina happened during the worse stretch of weather that winter. The temperatures plummeted and the roads thickened with ice and snow.

Bill, as he has in many similar circumstances, did the duty. He climbed the mountain in his four-wheel-drive truck, retrieved the patient and took him to the doctor that day and for several days thereafter. Bill wouldn't even accept gas money.

That story isn't in his book, but I mention it here and will probably have to defend my reasons for wanting it in. In fact, I expect some resistance from Bill to telling this. He would be the last to call attention to his good deeds. Know that I have fought to preserve the record as it is. A foreword to a book should legitimately present the writer's good points.

Bill's slice-of-life vignettes that constitute the main offerings of this book are "other" centered. Some tell what it was like to work for Baker's Hardware, a fixture on High Street for decades. He tells you of the inner workings of the University Dairy Farm on the Mileground. You can learn about the Morgantown Glassware Guild. Wonder how life was like in early Evansdale before the university spawned a campus there? Bill grew up there and tells you.

In narrating the lives of departed acquaintances, he sounds a tone in prose much as Thomas Gray did in poetry with his "Elegy Written in a Country Graveyard." As we know, the lives of ordinary people more often than not are extraordinary. Like Bill, they just don't receive or even want the publicity.

In this memoir, you will find the names of some of the famous people of our county, and some whose merit should have made them famous but out of choice didn't. At other times, Bill's writing puts me in the mind of Sherwood Anderson when he profiled distinctive characters in Winesburg, Ohio. This book introduces you to many names that are special to their families, to Bill and now, by way of the printed page, perhaps to you.

In one of my English courses at West Virginia University, one of the professors posited that the greatest literature is moral literature. In many of Bill's tales, you will find a lesson, a way, a guide that can make you a better person. That is in essence how morality plays out.

Because Bill has had a large input and influence on my life since I got to know him in 1970, I from time to time mentioned him by name in a column I write for The Dominion Post. Out of modesty, Bill eventually asked me not to use his name. But I am sure pleased to let some of my admiration for him as a person and writer "hang out" in this foreword. Enjoy and be enlightened.

- Norman Julian

Author of the books Snake Hill and Cheat

Preface

In 2003 I surrendered to a yearning to write about some things in my life.

I knew I wanted to write about the men and women who have enriched it by just being there at specific times. They were all role models and I wanted to give them credit for helping at a time of need. At best, my tributes are only thumbnail sketches. Much more could be said.

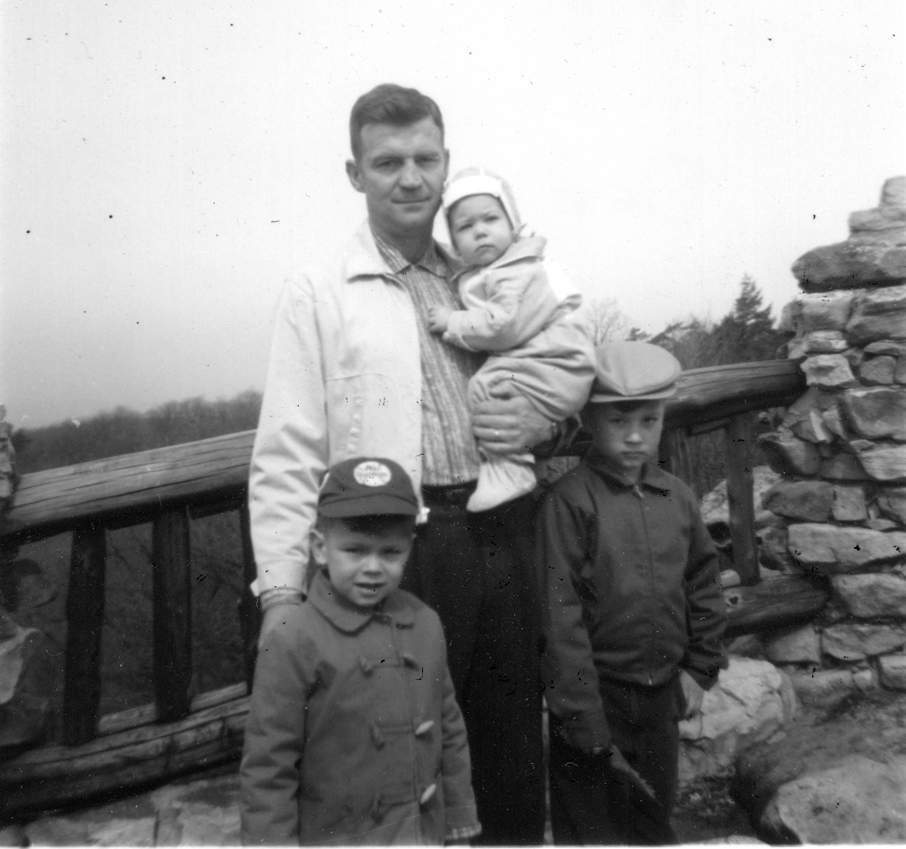

I also hoped to shed some light on the people and environment of my life for our children (John, Mark, and Jane) and our close friends. I thought others might be interested, too. A few even said so! At first I thought six pieces could fill the bill—one each on James Koontz, "Ma" and "Tater" Miller, James Gorman, Janie Caldwell, the Bonner family and the Stansbury family. As time went on other memories kept tweaking me with the realization that there were many more. Just telling the six would not provide a very clear picture. Now with dozens, the picture is clearer.

Early on, I had thought I might call the book something like Profiles of Plain People until I learned that some don't consider "plain" a compliment. (I do, for to me it means down-to-earth, genuine, and neighborly.) Another title I had considered was Evansdale Chronicles, but as I wrote, the territory my stories covered expanded to adjoining areas.

The lineup of stories has no rhyme or reason. The stories were placed in their spaces as they came to me and not in any planned sequence. Everything was written longhand.

With the help of others, my handwritten papers became this book. The search for someone to type was a little hard at first. Luckily, about 2004, Elizabeth Baker, Pastor of Tyrone United Methodist Church, introduced me to the Stevens, Ann and Ted. When Ann heard of my plight she agreed to type all of my stories and put them in her computer for easy access. A great service and gift indeed. Ted was involved also, giving good advice along the way.

After typing, came photocopying. Elizabeth Baker did this work for me until she was reappointed and moved. Then Jim Petitto of Petitto Mining Company graciously stepped in by assigning Peggy Leggett, his secretary, to the chore. I appreciate this service, which gave me draft copies I and others could review.

I am also grateful to Rae Jean Sielen at Populore Publishing for assistance in producing this book.

Lastly, many thanks to Norman Julian, my friend and neighbor, for encouragement and for writing the Foreword. (However, he did lay it on a little thick.)

- Bill Fichtner

- Introduction

- Foreword

- Preface

- James Koontz

- Eleanor "Ma" and Walker "Tater" Miller

- James Gallagher Gorman

- Jane Caldwell

- The Bonner Family

- Norton's Paper Route

- Frank Balint

- Horses of the Flatts

- Joe and Betsy

- A Billimerick

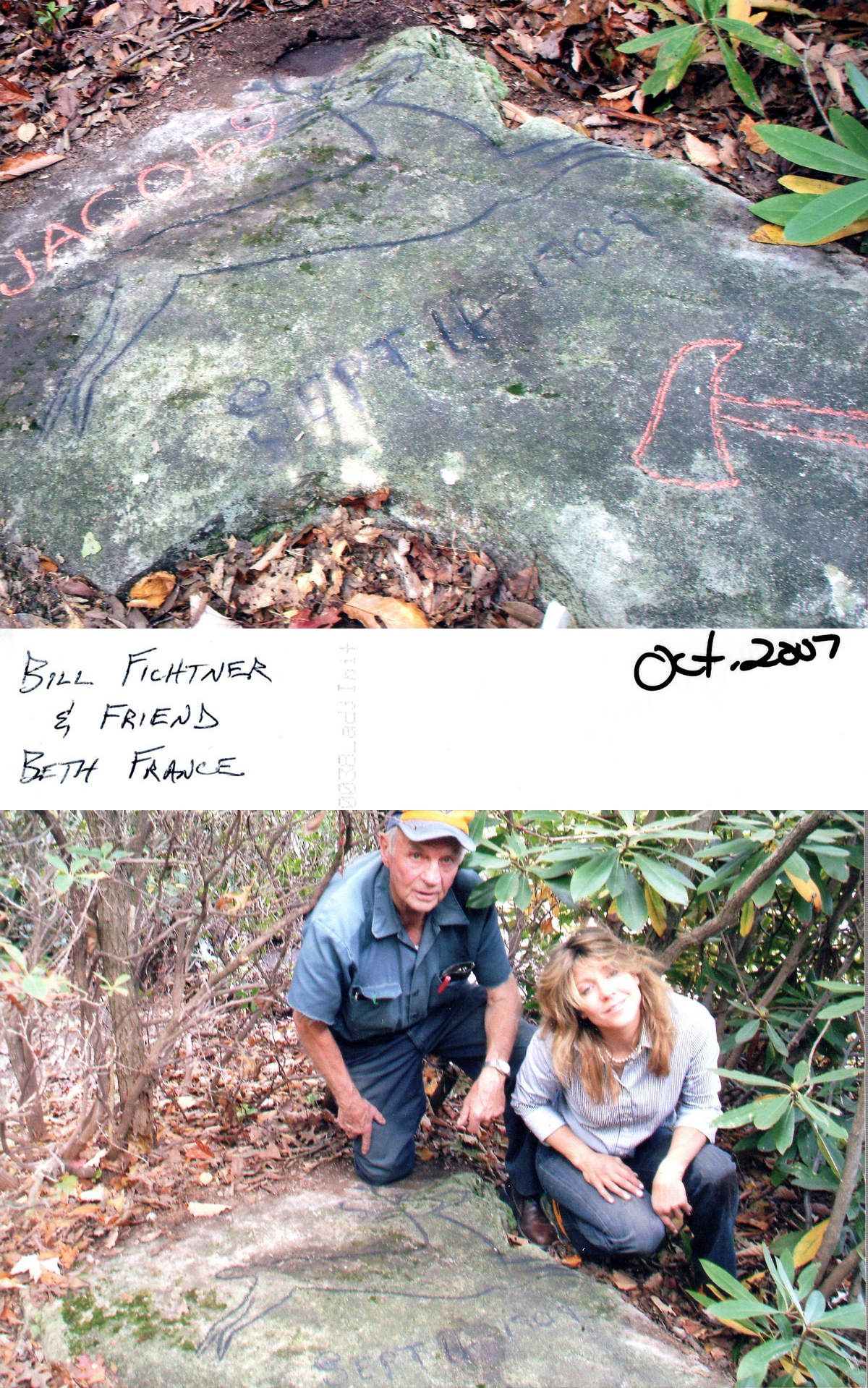

- Lady's Rock

- Camping

- Baldwin Addition

- Evansdale and Walnut Hill

- Edgar Lynn

- Norman Colebank

- Roxy

- Morgantown Golf and Country Club

- Old Man Mallow

- Clarence "Grease" Everly

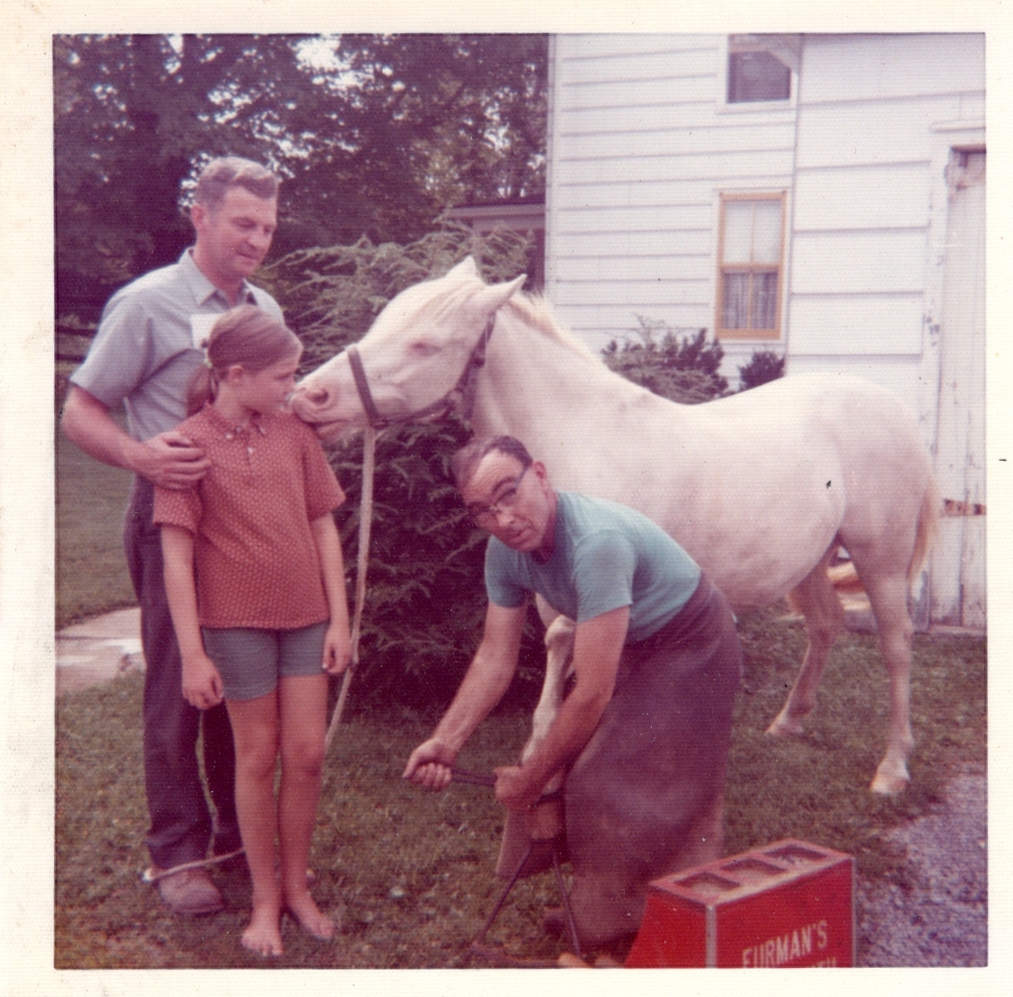

- Claude Furman

- Calving and Breeding

- Settlement House Wedding

- The Hayden Family

- Tom Kitzmiller

- Alfred Jones

- A Day in the Life of a Country Boy

- "Peck" Swearge

- Watching the Circus Arrive

- St Francis Football Team

- Landing Field

- Solomon Mckinney

- State Dairy Farm

- Sophomore Disaster

- Beaver Hole

- Postal Stories

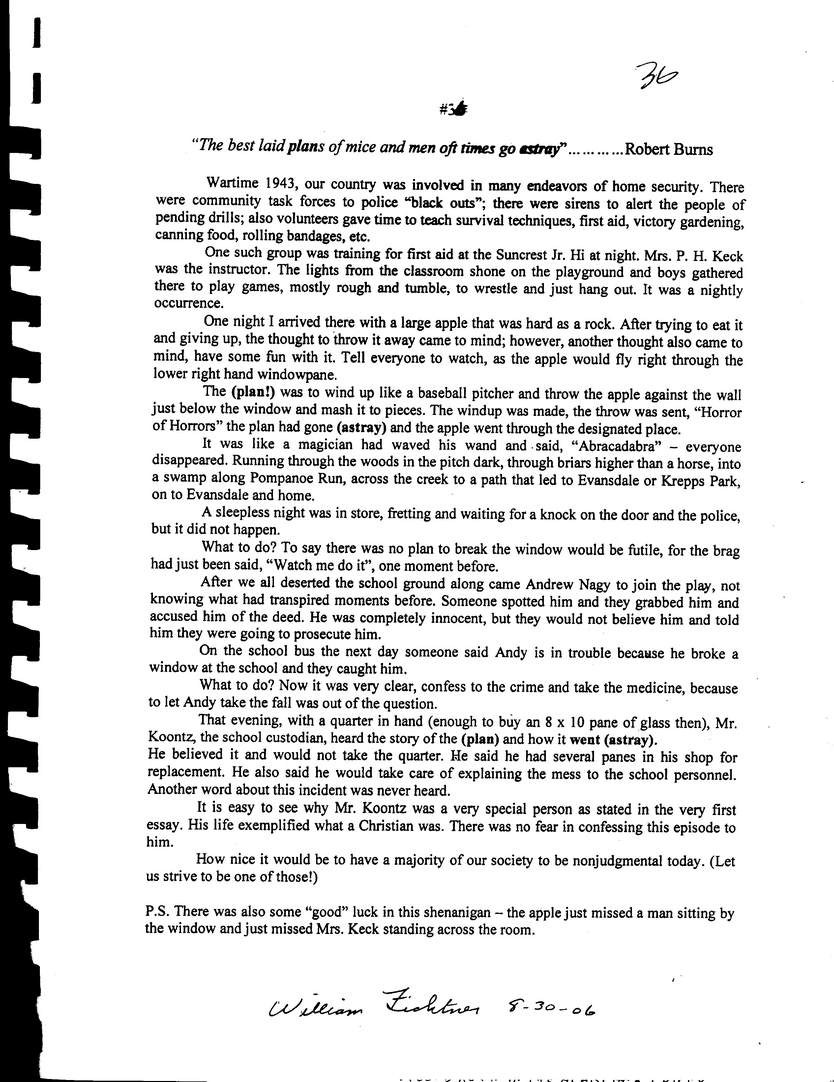

- Ode to a Green Apple

- Gay Buseman

- What If?

- Coopers Rock Visitor

- Stansbury!

- Thoney Pietro

- The Morgantown Glassware Guild

- Edmund H Flowers

- The Professors

- Sam Stansbury

- "I've Been Working on the Railroad"

- H C Baker Hardware

- The Homestead

- Sam Mason

- Deacon

- US Navy and OtherJobs

- Summer School

- Bonnie the Cow

- The Calling

James Koontz

To his peers, he was Jim. To us who were youngsters, he was "Mister." At first glance there was nothing unusual about him, and not too many people took a second look but those of us who knew him better were given a rare gift.

James Koontz was the janitor of Evansdale Grade School. Then he moved to Suncrest Junior High (SJH) when it opened at midterm January 1940. He lived in a little bungalow, the location that is under the pavement near the intersection of Patteson Drive and University Avenue. A service station, grocery market and an old mill are also under that pavement.

Mr. Koontz was never a person to interfere in another's life, but he was always on the sidelines ready to help anyone (little kids included) who needed something he could provide. He was always a pleasant man, as his countenance clearly signaled by his easy smile and crow's-foot wrinkles at his eyes.

The Depression of '29 turned him from a man of means to almost a pauper, except for some very near worthless real estate, which was located along Van Voorhis Road near Virginia Manor and Burroughs Street. Koontz Avenue ended at his original home that was left to him and his brother Charles, whom I knew very little about, but was also an honorable man.

The furnace room at SJH was his "office" and I delighted in visiting him there at noontime to listen to his stories of times past when he was younger. He had been to Florida several times; this awed me more than the moon landing, for I had hardly been out of Monongalia County, and Florida seemed like another world.

There was never any bitterness in him about being poor. I'm sure he was as happy poor as he was rich because of his faith in God, which he spoke sparingly about. The way he lived his life spoke much clearer about what faith in God can do to make life a joy.

Mr. Koontz took an interest in me, I think, because he knew a lot about my family and he knew that my father had died and I needed a male role model.

Mr. Koontz liked to hunt rabbits and squirrels for sport and definitely for meat. I liked it for the same reasons. So when he was going to hunt after school he would invite me to go along sometimes. On those times I would take my shotgun to school and leave it in the furnace room. No one seemed to notice me with the gun. (How different times were then.)

He would tell me of "exciting" games that his generation was involved in. Evenings, either at church or school, the communities would gather to face off on a spelling bee or have a debate, some times getting very lively. (Seems rather dull now with all that goes on in our society these days.) Also, elections were rather lively then; people were serious about their politics to the point of sometimes fighting.

Mr. Koontz was saving his money to buy a new car. One night he went to his church to find the congregation involved in trying to raise money to send a man and wife team of missionaries to Africa. They had raised all but $1,100. He said to himself, if he lived he could save more money for a car, but may never have a chance to have a hand in such a worthy cause again. So he gave his total savings, which was $1,100. He said it was the best money he ever spent. Those missionaries kept in touch with him for years with letters and pictures of their work.

This story describes better than I can the kind of man he was. His influence, along with several others like him, had a great influence on me and was partly the reason that I had a "part time" pastorate with the United Methodist Church for just over 20 years. Times changed; his real estate became very valuable and in the twilight of life, Mr. Koontz was wealthy again. Reminds me of the story of Job.

Eleanor "Ma" And Walker "Tater" Miller

Before there was television's Archie and Edith, there was Ma and Tater. Tater was built just like Archie, and he came on like a bull in a china shop. He was rude and insulting to his friends about their politics, religion and private lives. Eleanor was a peacemaker for his tirades. She went about picking up the pieces and getting everything back to order, and after all was settled, Walnut Hill went back to being a normal, loving community of people who cared for each other, including Tater.

During the Depression, Ma and Tater started a small neighborhood store in an upstairs room that was on the level of Star City Road, later University Avenue.

Their little store became the center for all of the social activity on the hill. People waited for the bus there. Caddies from the golf course ate their dinners there. They would buy a loaf of bread and enough bologna to use it up and share the cost. Dessert was an individual transaction. All of the news on the hill came through the store. If you wanted to know anything about anyone you could find the answer at Miller's Market.

The little store ran credit for the family, and I'm sure they got beat out of quite a lot of money. Some would charge there, and when they had cash, went to the A&P. Our mother would never do that, even when some told her how much she would save.

There was a time when we had no income and for a long time never paid anything on our bill. But Ma never turned us down for staple foodstuffs. When we began to get on our feet, Mom told Ma to put the big bill ($285.00) aside. Then she would pay $2.00 a week on it and keep current on the other bill weekly.

There were two children to Ma and Tater: Maurice, who was two years younger than me, and Eleanor Jo, who was 10 years younger. Maurice and I have been good friends all of our lives.

Tater's bellicose personality was really his defense for, like Archie, underneath he was really a pussy cat and generous to a fault that if he didn't "holler," people would have taken advantage of him. His own young life was hard and poor. When he was 15 he was hurt in the coal mines. He was caught between the coal cars and a brake; somehow it wrapped him up and crushed his shoulder. That injury came back on him in his thirties and nearly took his life, and from then on he had to be treated daily (by Ma) to clean the wound of puss and rebandage it. His left arm wasn't much use to him after that.

James Gallagher Gorman

1859-1941

When you draw up a set of criteria for a role model it generally goes along these lines-moral, fluent, personable, good looking, good sense of humor, able to easily articulate ideas and a host of other good things.

James Gorman had none of these qualities when I knew him. I'm sure he had these qualities in previous years, but when I was born he was 68 years old, and before I really knew him he was nine years older so my memory of him was formed in only four years because he died when I was 13 years old.

James Gorman was my great-uncle, my mother's favorite uncle, for reasons that I came to know through her, and not only her, but by people who knew him "when."

The job that suited him the most was "school teacher" in his younger years. All of the ex-students I ever met liked to tell me about what an impact he had on their lives. He later became a bricklayer and followed that trade until an accident that nearly killed him in 1902. He fell from a scaffold and hit his head—he never completely recovered. It changed his personality-he was more austere after that. His brother, Alfred, was hurt learning to shoe horses and was paralyzed. James, being the only single man left in their family, the care of Alfred fell on him. This responsibility caused him to remain single all of his life, though he did have prospects for marriage. Later he had a stroke that impaired his speech so that it was difficult to understand him. Thus, not many people came to visit him, and my friends that occasionally went to his place with me were afraid of him because he sounded angry when he spoke, and they couldn't understand him.

When I first began helping him, I had trouble understanding him, but I got so I overlooked his voice and manner and truly enjoyed being with him. He taught me "farm things." I always loved farming. He and I together hardly made a man, but he did something to contribute to his cupboard every day. He taught me how to milk, how to set a hen, how to shuck corn, to put up hay (the old method), to aid a birthing heifer, to butcher hogs and how to use a scythe. He always wanted to teach anyone anything he knew. He taught reverence for nature and explained many of the mysteries of nature to me.

His estate consisted of 30 acres and a brick house on Chestnut Ridge Road. He had no money to speak of, but when he died, he left my mother one-half interest of his property.

I wanted her to keep it but we were flat broke and in debt (in those days you had to pay your bills), so my mother sold her interest to Sam Ivill for $2,500; however, that was a godsend at that time.

The farm was located where Mylan Pharmaceuticals is at the present time.

Jane Caldwell

1886-1976

Jane "Janie" Lancaster Caldwell (Ole Jane) was a black woman when black wasn't cool. In the '40s she was a product of the time and the social structure in which she was born. Every road to success was blocked to her. Separate but equal wasn't a reality. The only reality was the separate part.

Janie never went to school; she was illiterate. Janie worked for a pittance of what white people worked for, but she never let her circumstances keep her from enjoying life, probably more than those who were successful. I met Janie by accident when I was about twelve years old. I was following a Mr. Wright, who was mowing hay with a team of mules in the area of Janie's house, which was located where the WVU "Ag. Sciences" building is now located. From her house you couldn't see another house. This area is the Evansdale Campus of WVU now. She lived in a field, in a "three-rooms-in-a-row" shanty. The thing that lured me to her was the fact that while walking by her house I saw chickens, rabbits, geese, ducks, two goats and a pack of dogs. It looked like a utopia to me.

Janie was good to all of our gang of four ragtag ornery boys: Maurice "Sookie" Miller, "Jolly" Clarence Jolliffee, "Corny" Sands and myself. We usually took food to her; she would cook it for us, and we would have a picnic together. Sometimes the food was game -r abbits, opossums and raccoons. The man that lived with her, "Pete" Floyd Wilson, worked in a slaughterhouse, and he provided certain cuts of meat that "white folk" didn't eat. However, after she cooked it we all agreed there wasn't any better fare anywhere.

All of our associations with people have a way of affecting our development as humans. Janie was no exception. She taught me some great lessons about life. If she was ever gloomy and sullen, I must say, I never saw it. She was always happy and when she came on the scene everyone got happy also. I recall hearing her several times when she was tired and worn out say, "Lord, I is so glad I is black." I wondered about that statement because I thought being black was really what held her down. (How many people do you know who are always happy?)

Janie was truly a success because happiness is the true badge of success.

She was also very funny. She was about five feet, six inches tall and weighed 225 pounds when she was at her desired weight. She did not want to lose even five pounds. When sometimes she would drop down to 210 she would say it interfered with her hoeing the garden. She said when she struck the hoe down hard that she felt herself bounce up from behind. She said, "When I hit that hoe down I want it to go in the ground."

Janie was strong as any man. In hot weather she took her cast iron, coal cookstove out in the yard. Believe me, that stove was very heavy. She left it there until cooler weather prevailed.

Describing Janie's looks was easy then, because all you needed was a box of Aunt Jemima pancake flour. She looked just like that picture. When she got older she got diabetes. Eventually, while living in the county home, she had both legs taken off above the knees. It saddened me to see her that way.

I visited her there before she lost her legs; she was the life of the ward of about 20 women. When I left her one evening I heard her shout to the others, "There goes my baby." I felt a little pride in her statement even though I am white.

We named our daughter after her. This, of course, is just a thumbnail sketch of her life.

The Bonner Family

S. R. Bonner (grandfather), Robert and Elizabeth (son and daughter-in-law), Robert Nelson Bonner (Robert and Elizabeth's son)—these were the first people I knew outside of our family.

When I first knew them, they lived at the corner of Riverview Drive and Star City Road in a large brick house. In back of the house, the building that served as a large garage was built as an ice cream dairy.

Bonners would allow us kids to play around, occasionally doing a few errands; then they would take a lid off of a 10-gallon milk can, fill it with ice cream and let us stand around it with little flat wooden spoons and eat our fill. Sometimes Mr. Bonner would give me a pint to take home to the family.

S. R. Bonner would make a large "brick" of ice cream, then put flat sticks in it. At intervals he would take a large butcher knife and cut between the sticks. This done, he then dipped them by hand into chocolate that stayed liquid at room temperature, put them in the walk-in freezer and wrapped them later.

The Depression ended the ice cream business, and Bonners relocated to a nice bungalow at what was then the end of what is now Eastern Avenue. There were only four houses on Eastern Avenue from Burroughs Street to the end—Hoards, Summers, Everlys and Bonners.

They started a poultry enterprise, bought a cow, got two pigs and raised about two acres of beans for market. To me, this was like what heaven would be like.

My brother, John, and I spent a lot of time in the summer there doing whatever was to be done. Picking beans mostly, but there was fun too. Sometimes Mr. Bonner would take us to Cheat Lake to fish. At Christmas they would butcher as many as 300 chickens and turkeys. We would help them, and Mr. Bonner would give us a turkey (he raised a few for special friends each year).

It would take a book to write all of the things we three got into. Bobby and John were together most of the time while I stayed mostly with the adults—I was three years younger. Mrs. Bonner defended me against all of the teasing that Bob laid on me. I was extremely bashful and she would always be there to assure me he was only kidding.

Mr. and Mrs. Bonner treated John and me just like family. Their rules for conduct were the same for us as for their own son. Our mother never worried about us when we were with them.

In my early life Bonners (all of them) influenced me more than anyone else outside of my family.

World War II separated us, never to resume that close relationship again; however, our feelings for each other and their families have not diminished.

Norton's Paper Route

In 1937 Arnold Norton had an evening paper route (Morgantown Post) of about 110 customers. In those days the paperboys owned their routes, and when they wanted to quit, they would sell or lease them.

John Fichtner, my older brother, bargained with Arnold to rent his route because he couldn't afford the purchase price. The route paid 15¢ a week per customer, of which the carrier received 5¢. John agreed to carry the route for half, or $2.75 per week.

The route was a combination of two routes. The paper company (same company as today) would leave 85 papers in the recessed doorway of Pierce's Drug Store, two doors up from old Mountaineer Field, on University Avenue. Deliveries were made on Stewart Street to Jones Avenue, then up Jones, taking in little side alleys, to the junction of North Street. Then he would deliver Virginia Avenue, back to Jones Avenue, go up an alley and hit Warrick Street, follow it to University Avenue, go out Dillie Street, come back to University on Gilmore Street and stop at our house next to Eighth Street.

The paper company then left 25 papers on Norton's porch, first house after crossing Riverview Drive on University Avenue. I helped him often by delivering the remaining 25 papers in Evansdale, taking Riverview Drive to the end, then Fairfax, Hawthorne, Vassar, Dudley and Rawley back to University as far as what is now called Evansdale Drive. In the area just mentioned there were only 52 houses. We had only two customers on the east side of University Avenue.

My brother did all of the collecting for the entire route. I talked with him by phone to Atlanta, Georgia, the other day; we reminisced about those times and how scarce money was, and he said he still remembered one customer that owed 45¢.

Another situation was brought to my attention while talking with Whitey DeMoss (a morning paper carrier for the Dominion News). His route was in the business district. A doctor in town deducted 3¢ from the 15¢ because of a holiday in the week. Whitey had to stand the loss.

The daily price was 3¢ or 15¢ for six days. The company always left an extra paper for us in each route, and if we were lucky we could sell it. (I only remember selling one to a man in a car one time.) However, I used my extra paper several times at one particular house on Riverview Drive because they had a dog that waited just inside their hedge for me every day. So I threw the paper from as far as I could; sometimes it landed on their porch roof and sometimes in the bushes, so I'd throw my extra paper. The dog never came out of their yard to threaten me, but he definitely challenged me if he found me inside his yard. My arrival made his day. I was 10 years old at the time.

Frank Balint

In 1934, Frank Balint and his half-brother John Gazi moved from Star City to Evansdale to live with their grandmother, Mrs. Enyondi, because their mother had contracted TB and had to go to a sanitarium for long-term care.

When their mother was allowed to move back home, John returned to Star City, but Frank stayed on because he had acquired a Pittsburgh Post-Gazette paper route and he said he didn't want to lose that income.

The route started at Campus Drive downtown and ended at Somerset Avenue near Star City, a distance of over two miles. It consisted of 27 customers and paid 1/2¢ per copy per day or 13 1/2¢ a day for a total of 81¢ per week.

Horses Of The Flatts

The clippity-clop of a horse walking on the pavement would alert me to stop whatever I was doing and run up to the road to see who it was and to see the horses, for I knew almost every horse at our end of the county.

Mr. Billy Wolfe had a team of horses that were not very well matched. One horse was lanky, tall, long and not too heavy. The other was a short bay; however, Mr. Wolfe could get them to work together pretty well.

During a storm, power lines came down on his barn and burned it to the ground. Both horses and everything in the barn were lost. The power company replaced his horses with a very nice team: a gray named Queen and a bay, Bird. They were kept in the barn on Willowdale Road where the parking lot for the hospital and football stadium is now. Wolfe lived on Chestnut Ridge Road across from where the Elks Lodge is now.

Mr. Frankhouser lived just down the road from the Wolfes. He had a team of mules—I didn't care about mules the way I did horses. Mr. Pierpont lived at the Chestnut Ridge Road and Pineview junction—and always had one or two horses. Vandervorts also had a small white horse, Barney. Adam Thompson lived where North Elementary is now. He had a very nice Percheron named Dan that he bought from J. W. Summers. My great-uncle James Gorman rented Dan and Barney at different times. Mr. Gary lived where the BB&T outside windows are and had a nice team of black horses. Mr. Edward Hunter kept riding-horses at Burroughs and Van Voorhis Road, topping the hill on Van Voorhis Road where Morgan Manor is located. Mr. J. W. Summers had a team of black horses down on West Run below the garden center. Zonnie Christopher had a team of horses on down. Burley Fordice had a little, black carriage horse named Babe, and up on Bakers Ridge, Mr. Baker had a bay carriage horse. Both he and Burley had routes that they sold garden produce, eggs and chickens. Since there was no refrigeration then, they brought live chickens. That way, if no one bought them they would take them back home and try again the next week. (How many women do you know that would butcher chickens on their back porch? Many did back then.)

The teamsters made their livings working their horses. Mr. Summers said he got $5.00 a day for him and the team when they built the old Morgantown Country Club.

Later, Billy Wolfe got $7.50 a day scooping out basements and dredging streams, as well as plowing gardens and other farm work.

The teamsters never mistreated me, but I know that they weren't thrilled to have me around their stable; sometimes, though, they would let me ride the horses to water after they were done working them. I would get in their wagon when it passed our house, ride it to their home and pet their horses while they removed their harnesses. I would maybe get to ride them to water, then walk all the way home happily smelling like a horse and dreaming of a day when I would have a horse.

Joe And Betsy

Driving to our farm on Bee Run I saw two people standing with their backs to the road looking down at the grass. I passed by but stopped and went back to make my acquaintance of new neighbors and see what they were looking at (I am kinda nosy).

Joe and Betsy Viola were their names and their bodies were shielding a whole garden from sight. They were admiring their horticulture prowess—peppers and six tomato plants or some thing similar.

That garden was the first step on a journey that has gone quite far, but is in no way near the end.

I was blessed to be in on their maiden voyage into the realm of the "Agricult," and it provided me with a vast opportunity to observe how two people dropped in the wilderness, without a clue, would succeed. Like the television show Survivor, it has been interesting to say the least. While I thought I would be able to show them something to help them, they turned the tables on me and showed me things I have never seen before—such as:

1) Moving a flock of sheep = Bend over the sheep, put your arms around its girth, give a quick jerk lifting it off of its feet and carry it where you want it. I hope you aren't going far.

2) Loading pigs in a pickup = Lure the pig up a steep ramp with food, go backwards in front of the pig, back into the crate and hope it has a gate on both ends. If not, Joe would have to ride with the pig.

3) Bagging ewes to check pregnancy = Walk behind the ewes while they are eating, reach in under them and feel their bag to see if it is swelling in preparation for birthing. By the way, be sure to remove the ram before you start.

Opportunities abounded for someone to play practical jokes on them, but since I'm not that kind of guy, I let them pass. However, I must say they proved themselves equal to every situation that confronted them. The learned well about gardening, poultry for eggs and meat, rabbits for meat, sheep for market, wool for spinning and knitting and made split oak baskets, better than mine. Cats for company (and for reasons to visit the widow across the road). Then one day they were gone far away. I miss them but I know they are prepared for whatever comes up. After all, what better baptismal font than the water that flows through sheep pens, for farmers?

I have overlooked some stuff, I'm sure, but as all biographers know, "some stuff" needs to be overlooked.

A Billimerick

We once knew a gardener named Bill.

Through the tall grass he watched as we tilled.

Then one day he stopped by

and in amazement he cried,

"Why, it's no bigger than an ant hill!"

We once knew a farmer named Bill

who is bewildered to this day still.

He could not understand

why we carried the lambs

to greener pastures just over the hill.

We once knew a prankster named Bill

whose wit was as sharp as a quill.

When the light bulb came on

he would creep to our home

and hang vampires to give us a thrill.

We once had a good friend named Bill

who would visit and we'd laugh to our fill

of the beauty and lure

of the lady next door.

Tell me, Bill, do you visit her still?

- Joe Viola

(He wrote this to get back at me, "Billa.")

Lady's Rock ...

Lady's Rock, Bigger's Rock and The Island are three names of places that have very little meaning today (2002), but until the mid '40s everyone in Seneca, Walnut Hill, Evansdale, Brewer's Hill and Star City was more familiar with these names than with the names Coopers Rock and Cheat Lake.

These names represent three places along the Monongahela River parallel with the boulevard from Eighth Street to the WVU Coliseum. Lady's Rock, being the most popular, was closest to Seneca and the safest place to swim. The river bottom sloped gently from the shore for perhaps 20 to 25 feet to a depth of about 48 inches where the rock prevented the swimmer from going farther out into the river without climbing over it. Most of the time the rock was about six inches below the surface. Nonswimmers and little children could play in the "relatively safe" place between the rock and the shore. I learned to swim at this place.

Bigger's Rock was about 100 yards downstream. It stuck out of the water about four feet at its highest point and sloped to the water so a swimmer could get up on it and rest or sunbathe. Bigger's was 40 to 50 feet offshore; the bottom sloped only about 15 feet to a sharp dropoff into deep water with unstable current from there to the rock, not a good place to swim unless you were a good swimmer.

The Island was really a peninsula that was about 30 feet off shore and was quite long. It was an interesting place to explore and to fish, also a good place to catch turtles; in winter people who trapped said it was also a great place to catch muskrats. The Island was just below the WVU Arboretum.

I want to clear up the statement, "safest place to swim," mentioned earlier. While lots of people played at these places, it was not safe by any present day standard. It was very risky because the Mon River was an open sewer; raw sewage from Morgantown, Fairmont and every home and industry in the whole watershed went untreated into it. The surprising thing is that more people didn't contract diseases than did. Also, drownings were a frequent occurrence along the river.

Fishing consisted of "mud cats" only. They were the only fish that could live in such polluted water.

In the late '40s or early '50s the Corps of Engineers built new locks which raised the river pool over four feet, thus covering the aforementioned places.

The economy improved at that time; people got cars and recreation moved to Cheat Lake and Coopers Rock. I remember one 4th of July when Sunset Beach had over 1,400 swimmers and picnickers and over 1,000 hikers and picnickers were at Coopers Rock.

Through conservation efforts things have improved at the Monongahela River. All kinds of fish live there, and sewage and industrial waste have been removed. Now it is a recreational location and enjoyed by lots of people again. Let's hope it continues in this direction.

Camping

Camping today means tents, gas-fired stoves, fly repellant, electric generators to produce power (for light, TV, radio, refrigeration, even shaving), bunks or air mattresses and potable water. It also means some form of protection—cell phones and guns and adult participation and regulation. The campsites are located somewhere with toilet accommodations and even showers and, of course, plenty of food.

Camping at Booth Creek and on property owned by Bill Price at Uffington in 1940 for four boys from Walnut Hill was somewhat different. We—Maurice Miller, 10 years old; Clarence Jolliffee, also 10 years old; myself, 12 years old; and Bill Sands, 13 years old—had $14.00 among us to buy groceries for two weeks, $12.00 of which we spent right at the beginning and then $2.00 we held back to buy bread at Price's store as we needed it. What we really wanted the cash for was not so much for bread, but for tobacco (Bugler—5¢ a pack); we were not allowed to smoke.

Our camping gear consisted of a blanket each and a large tarpaulin, which we hung over a ridgepole between two trees and staked to the ground as wide as it would go, a hatchet, a skillet and a carbide lamp. The only clothes we had were what we had on, and several boxes of matches rounded out our possessions, except for some very rudimentary fishing tackle, string and hooks.

We generally slept outside of our tarp around a campfire, as the air there was much more agreeable because our $12.00 grub stake consisted almost entirely of pork and beans—need I say more about the air? The skillet was for frying fish, if we caught any. We had some peanut butter and a couple jars of mustard also.

There was a spring in the woods, not walled up, where we could fill our jugs. A little pool below where the water came out of the ground made it possible to hold our jugs down below the surface to allow the water to flow into them.

There were two swimming holes in the area appropriately named First Hole and Second Hole. First Hole had a high rock that you could jump from also. It had a large flat rock that the current flowed under, making it a dangerous place for poor swimmers. I recall Bill Sands, our best swimmer, tried to climb out on the rock and the flow took his feet and legs under the rock; we had to help him gain safety by pulling him out. We didn't swim there anymore. However, we did fish there.

Second Hole had a large rock also, but it was upstream and the current flowed away from it. The water was very cold even in July because it was shaded by trees and a very steep hill, which the sun fell behind early in the day.

We fished mostly at night with "throw lines." We tied our string to a stick in the ground about a foot high, and then we would tear a little slip of paper, make a slit in it and straddle it on the line with the light made by the carbide lamp. We could see if the paper jiggled, telling us we had a bite. Without the light we would just hold the line in our hand.

The only adult participation after one week was Roy Forman and Tater Miller, who came out to check on us. Lovers also came on Saturday nights and yelled and squealed among the bushes. On Sundays people came to wash their cars; they could drive into the shallow rapids between the two swimming holes and wash and rinse their cars.

Bill Sands had a little dog along, and one day it got bit by a copperhead right beside our lean-to tarp. The little dog started licking her leg and continued until all of the hair came off, but she recovered.

We set our beans close to the fire, and when they got warm, we would eat them right out of the can. We had no dishes when we fried fish—we ate out of the skillet.

With not catching many fish and spending most of our cash on tobacco, we were out of food two days before our transportation was to arrive, so someone "found" a potato patch and we got some and fried them in mustard.

We slept on the ground wrapped in a blanket with rocks and roots for a mattress. Our sleep did not translate into rest. Our toilet was in the woods. Our hatchet was our firewood maker.

Bill Price had a store and service station on Route 73 where we bought the bread. Some man bought our Bugler for us. A personality who lived nearby, "Cat Fish Molly Jarvis," fished there at the backwaters. She was well known in the neighborhood and even among the fishermen in town. I heard her name mentioned many times. When two weeks were over, we had enough of camping for the year. The following year we went for one week. Ernest Ogden went with us. He had a very leaky tent but at least it had ends in it. He was 16 years old.

With the present society we probably wouldn't have lasted one night alive, but what we did was not unusual for then. Some things are much better now, but not everything.

Baldwin Addition

Beginning at Furman's store going north toward Star City, the large house at the corner of Star City Road and Van Voorhis Road was inhabited by a family named Beckett, Mr. and Mrs. and two girls. The next house on the left was Geo and Mrs. Grow; next the Fleming family, Mr. and Mrs. and son, Jack (the radio announcer for WVU sports and the Pittsburgh Steelers); next Miller family; then Mr. Gump and Mrs., no children—they were the owners of the bus line in the 30s and 40s. Next were Tom and Mrs. Murphy and children, Tommy and Barbara. The next house was a brick bungalow; I don't have a name for them. Next was Victors. Now going down Baldwin Avenue was Dr. Davis, wife and daughter; Mr. and Mrs. Ridgeway; Leon and Mrs. Jacquete and children, Dick, Colleen and "Dee." Last house on Baldwin was Leon Jacquete's parents. Backing up a little to Ridgeway's was P.H. Keck and wife, two boys, one being Bill and the other I can't recall; behind them K. B. Wolfe, wife and three boys, K. B. Jr., Leonard and Franklin.

Returning to Star City Road at the intersection of Collins Ferry Road, going north on Collins Ferry, the first house was a log house occupied by two spinster sisters, Lessie and Laura Jacobs. Across the road was their brother, Jim, wife and children, Susan, Herbert, Andrew, David and Daniel. The next house was Fred and Mrs. Bierer and children, Fred Jr., Tom, Sam, Mike, Edward, Dave, Dianne and Jocelyn. Next was Stiles family and son, Albin. Now turning right on to Burroughs Street, the first house was Johnny Deets family; then Minnie family—I don't know about children in these two homes. Next Harry and Mrs. Schiffbauer and two daughters, Bonnie and Louella. Next was Lizzy and Will Nabors; next Walter and Mrs. Schiffbauer and children, Jeannie and Lawrence; then Mr. and Mrs. Ross Bolyard and I believe two girls—I have no names for them. Across the road was a path in the field to a house, Mr. and Mrs. Joe Summers and son, Adrian. Burroughs Street ends. On Van Voorhis turn right—Edward and Mrs. Hunter, who had a grocery store; next Federers, one son, Hubert. Next Charles and Mrs. Hartley, sons Charles and Robert. Behind them was Paul Wilson family, six children of whom I can only name four, Eleanor, James, Robert and Paulene. Russell St. Clair family also in back of Hartleys. Continuing on Van Voorhis, T. R. Clark family; Lucas family; Newlon family with two sons, Bob and brother; Lynch family; Drummond Chapel Church. House behind church was Bolyards and daughter, Audrey.

Across from Geo Grow house, Koontz Avenue turned right, first house Bumgardner; next Mr. and Mrs. Maurice and sons, Elton and Tommy. Next Mr. and Mrs. Cather and children, Dotson and Susan; next Koontz home place, Charles and Mrs.; brick house on left Quencen family and daughter, Nancy; Mr. and Mrs.

Woodford and children, Russell and Robert. Several others farther on. Mr. and Mrs. Sam Glass and daughters, Mary and Jeanine.

Drummond Street feeds off of Koontz Avenue. Right at the beginning the only family on it was Longwell, Mr. and Mrs. and the children, Loraine and Harwood.

This completes the loop.

Evansdale And Walnut Hill

Star City Road hereafter called University Avenue (approximately 1935).

1) Beginning on University Avenue at North Street going north there was nothing on the east side except the Morgantown Country Club until half way down Evansdale hill, so I'll go back to North Street and relay information on the west side beginning with Flannigan's Store to John and Mrs. Pitman's several chil dren, but most were grown at this time—Russell, Ora and Hans were still at home along with two grandchildren, Jack and Ronald Savage. Turn left on Evans Street, first house on right—Lawrence and Mrs. Clulo; next Chester and Mrs. Bean and several children; on left Mrs. Grant and two grandsons, one whose name was Scott. Next Mr. and Mrs. Joe and Violet Petso and children, Joseph and Anna. Next was S. R. and Mrs. Hodge and several children. Then Oscar and Kate Clingen. Arrive at Dillie Street westMrs. Nabors and children, Virginia, Ester, Jim, Bill, Paul and Perry; Jack Jolliffee; Mr. and Mrs. Shear family, Wallace being one of the children; Mr. and Mrs. Everly and son, Everett; Frank and Alice Jenkins and children, Harold, John and Thelma. Mrs. Watson; George and Nettie Joiliffe and children, Kate, Jane, Frank, Tom, Paul, Maude, Pauline and Emiline, and granddaughter Delores. Back to University and going north Grant and Mrs. Jacobs; Elijah and Mrs. Dillie. Turn out onto Gilmore Street, first house on left—Jim and Evelyn Miller, children Betty, Barbara, Bill, Danny; Gay Buseman and son, Bill. Later in same houseJohn and Lula Griffith and daughter, Sue Ann; next Earl and Josie Bucklew and children, Rose, Ruth, Noah .and Beatrice; Russell and Maime Corbin and son, Junior. Cross the street going backBill and Ida Sands, children Bill and David; Tom Froman later in same house; Rupert and Mary Chittum, children Ruth and David; Tom and Gertie Jolliffee, children Dick, Ruby, Clarence, Eloise and Margie; Bobby and Mrs. Hoke; Edgar and Stella Hoke, children Ada, Billy and Tom in back garage apartment; Mary and Frank O'Malley and son, Robert. Back on University AvenueWalker and Eleanor Miller (Alice and Steve Melligan, Eleanor's family) and Maurice and Eleanor Jo Miller's children; Roy and Ann Richardson later in same house; Mr. and Mrs. Skaggs, children Louise, Mary and Patty Sue; Perry and Bessie Corbin and Elizabeth (Perry's daughter by his first wife). Next our house—my grandfather John Selby, my mother Clara and father Charles Fichtner, children Ruth, Helen, John, Bill, Jessie Lynn and my mother's sister and her children, Edgar and Charles.

2) Riverview Drive left side—Bonners, S. R., grandfather, and his son Robert and daughter-in-law, Elizabeth, with their son, Robert N.; Ray and sister Jenny Dillie; Mr. and Mrs. Hawley; Mr. "Cap" and Mrs. Wilkins, children Ray and Frank; Mr. and Mrs. Daughtery; T. D. and Mrs. Gray, children Margaret and Tom. Crossing street and going back—Mr. and Mrs. Short; Mr. and Mrs. Casto and daughter, Dorothy; Mr. and Mrs. Jennings and son; K. C. and Mrs. Westover and son, Bill; Mr. and Mrs. Baldwin, children Edward, Bob and a daughter; Mr. and Mrs. Northrup; Mr. and Mrs. Puhlman and daughter. Fairfax Drive connects to Riverview at this point, following left, first house—Mr. and Mrs. Tom Zinn and son; Mr. and Mrs. Livisey, children Maxine and Alice. Later in same house—Mr. and Mrs. A. J. Dickey and two sons; Mr. and Mrs. Bradley and daughters, Iona and the other I don't recall. Crossing street—Mrs. Strawser and children, Charlotte, Maxine and Violet; Mr. and Mrs. Brown and daughter, Jean Rae. Next Fairfax joins Oakland, only two dwellings on Oakland Mr. and Mrs. Holland and daughter, Dottie. Across Oakland at junction of Dudley—Mrs. Wright and sons, Robert, Kenneth and Willis at Rawley junction.

Turning right onto Oakland from Fairfax, the next right turn is Hawthorne—Mr. and Mrs. Johnson and daughter, Jeanette; Mr. and Mrs. Harris and daughter, Susan. Hawthorne ends on Vassar. Left on Vassar comes to Dudley, west side first house Mr. and Mrs. Lawrence and two sons; Mr. and Mrs. Townsend; Mr. Ogden, children Helen and Ernest; Mrs. Osborne. East side Mr. and Mrs. Rex Ford and daughter. Dr. and Mrs. Pursglove lived on Vassar across from Dudley; Mr. and Mrs. Madera lived on same side 1 1/2 blocks east. That was all of Vassar.

Going back to junction Oakland and Rawley, going south on the left—Mr. and Mrs. Samuels, two sons Harry and another I don't recall; a fellow who was a state policeman; Mr. and Mrs. Shank and son, Carl; Mr. and Mrs. Hyre and daughter, Jackie. On the west side from Oakland—Mr. and Mrs. Brand, two sons Harold and Wayne; Miss Adelaide Kuhn; Mr. and Mrs. Nick Cantis; Mr. and Mrs. Charles Hayshen and daughter, Mable; Frank and Mrs. Smell and son, Joseph; Mr. and Mrs. Albert Kuhn, two sons Dickey and Bobby.

Riverview Drive back at University Avenue north—Mr. and Mrs. Norton, children Ralph, Arnold and Alice; Mr. and Mrs. O'Dell, two sons Donald and Melvin; garage apartment in back, Mr. and Mrs. Maddox and son, Brice; Mr. and Mrs. Wade and son, James; Mr. and Mrs. Stevens and daughter behind Wades; brick house that I don't know who lived in; brick garage apartment next; Mr. and Mrs. Grubb and several children; Creed and Mrs. Boyard and daughter, Eleanor; Mr. Hofer, sons Herb and Ralph; Charles and Mrs. Summers and son, Wendell, daughter Jeanie. Mr. and Mrs. Boyles and children, Jack and Patty; Richard and Mrs. Wilson and son, David; Mr. and Mrs. Rich and sons,Elmer and Woody; Newton and Mrs. Smith and children, Virginia, Opal, Gertrude, Willis, Bob, Loretta, Jim and Lena; David and Caroline Davis and children, Don, Howard, Elaine and Lillian; Mr. and Mrs. McCartney, children Kenny, Helen and Wanda; George and Lena Black and children, Frank, Eileen and Thelma; Mr. Jim Koontz; in back of Jim Koontz, Mr. and Mrs. Maust and children, five boys and one girl. Donald Maust was one of the boys. Cross the creek in Furman's Store and service station—Mr. and Mrs. Furman and son, Leslie lived up overhead.

Now going back to halfway down Evansdale hill east side to a large brick building, two upstairs apartments—Balog family, children Alec, Louis, Joe and Edith; also Nagy family. Hawks Nest Tavern was on the main floor (whiskey still in basement). Next double house Vargo, children Mike, John, two more boys and two girls. Reels and kids, son Dewey and a few others. Large house—Victoria Shumur and family. Turn right on Ingle wood Boulevard, first house left—Mr. and Mrs. Popp, two sons Adolph, Steve and daughter Mary; another Mr. and Mrs. Nagy and children, Nick, Julia, Margaret, Olga, Andy and Albert. On the right Mr. and Mrs. Kalo and children, Joe, Jasper, James and Rose. Up hill in back—Mr. and Mrs. Pava, children Mike, Joe, Goldie, Kalmine and Elmer; another Popp family with daughter, Nadia. Back on University Avenue, next—Mr. and Mrs. Carroll and daughter, Marie.

Oakland Avenue, cross University, turn right. All the houses on this side were built without much planning because this area was a fairground before and most of these houses were built around the racetrack. First house was a name Salish; I don't know anything about them but later Jay and Ann Sellaro lived there. Next Mr. and Mrs. Lucas and children, Ernest, John and Ella; Helen and Steve Dadich and children, Steve Jr., Jim, John, Helen, Elizabeth and Margie. Next, Mary and Joe Dadich, children Erma, Viola and Joe. Next, two Hungarian churches, First Baptist and Reformed; Mrs. Sass and children, Julius, Carl, Marie, Ester and

Elizabeth; George family and children, Art, Joe and Goldie; Mrs. Enyedi, daughter Susie and grandson John Balint; Kewikoska family, children Freda and Charles; Joe Robleska, who lived in an apartment above the Kewikoska family; and somewhere, Louie Chaff; Bubenko family, children Teresa, Helen, Joe, Susie, John and Jim; Stupar family, children Frank, Joe, Mike, James, Ann, Mary, George and Steve. Back on University—Zulcoska family, children Mike, Bruno and Rose, and Rose's son, Joe Curtis. Next, Libert family and son, Art, and we are now at the end of Evansdale.

Edgar Lynn

Edgar Lynn was born on February 24, 1916. He was the issue of Jesse Lynn (father) and Jesse Selby Lynn (mother). His father drowned when he was 2 1/2 years old in an effort to save another man. They both drowned. Edgar was my first cousin.

All of my recollection of him was in the early part of my life, probably before I was six years old. He was my role model because he was reckless and carefree. At a time when all the rest of my family were seriously struggling to keep body and soul together, every day was a grind.

Edgar had time for me occasionally, and those times have proven to be jewels of my memory.

He took me to pick violets in the woods below our house, and a couple of times he took me to the "Seneca Woods," where there were many more kinds of flowers: violets—white, yellow and blue—blood root, phlox, trillium, wild geraniums and others. He had to carry me most of the way back because of the steep hill (Eighth Street).

Seneca Woods began at the bottom of Eighth Street and the end of Beechurst Avenue. There was a brickyard there, Morgantown Brick Company.

Brick kilns at the bottom of Eight Street in Morgantown WV

Source: WV History On View.org

It was abandoned; only igloo-type kilns were there, and in the ones that had not fallen down some hobos lived (men on the move looking for work, not dangerous people, just people suffering through the Depression).

Beyond the brickyard was a path through the woods gradually sloping up with a wide place on each side where the flowers grew. Today, the place is Jerry West Boulevard. He said the flowers were for his girlfriend. I never saw her nor did anyone else. I could not imagine him with a girlfriend at that time as he was rather reckless, but he was also a sensitive person.

Edgar was a naturalist; he loved the outdoors and most of the time in the summer he would have a snake in his pocket. He caddied at Morgantown Golf Course and was nicknamed "Snake." He spent many nights on the greens rolled up in a quilt. He had other pets. I recall three small "possums" in the washhouse and also a pet chipmunk. He had some rabbits, and I recall two pet rats—one brown and white, and one black and white. He called them jelly beans.

One night he killed a skunk and was so proud of it he brought it in the house to show my grandfather, as he was an invalid and could not walk. The skunk was dripping musk. The skunk went through the whole house and almost asphyxiated everyone. One time he put a snake in bed with his brother, Charles, to get him up. It did! He brought a white horse home one day, said he found it and he put it in our little chicken house. He put me on it and led it out to the cottonwood tree several times. I wanted him to keep it, but the horse's owner had another idea.

Edgar was known on Walnut Hill as the songbird from hell, singer of country and folk songs. Not because he was good, but because at night, when most people wanted to sleep, Edgar wanted to sing (on our back porch). While his voice had no recognizable classification, it was loud, thus he was heard over the entire neighborhood. Some of the songs I remember parts of are "Cowboy Jack", "Birmingham Jail," "Can I Sleep in Your Barn Tonight Mister" (to the tune of "Red River Valley"), "Oh! Susannah," "Little Brown Jug," "They are Burning Down the House I was Brung Up In", "I Wish I Was Single Again" and "The Old Apple Tree in the Orchard."

Edgar joined CCC (the Civilian Conservation Corps) when he was old enough. That act probably saved him from a life of crime. I was awed by his uniform when he came home, also his muscles. I thought he was the strongest man alive. Of course, being 11 1/2 years younger, I was easily impressed.

Later he got a job in the silk mills in Bloomsberg, Pennsylvania (his Grandma Lynn's home) and left Morgantown forever. Then he joined the army during WWII and we never saw him again. He wrote to my mother a few times, married a girl in Germany, had three girls and the last we heard he was in Baltimore, Maryland. He sent pictures of him dancing with a little girl, his own perhaps.

Because he had time for me, he gained a special place in my heart; however, older people in the community were glad to see him go because of unpredictability. My sisters were two of those people.

Norman Colebank

The best coach I ever watched was not a Big 10, SEC, PAC-10 or Big East team coach, but a coach here in Mon County. I have said this many times in sports conversations. His name is Norman Colebank. He coached the Cheat Lake Junior High team when our middle son played there. I did not attend any practices, but I'm sure there were times when he had to raise his voice to get attention. However, when the game started he fielded his team and took his place calmly standing on the sidelines in the middle of his reserves. He became a member of the team, watching for a weakness in the opponent that they could exploit. He substituted so all could play. He encouraged his little boys because beside him they were all little boys.

I do not know what his won-loss record was. I doubt if he knew, but figures are not all that is important. We, the parents of those boys, knew that every day they were with him they were winners for the things they didn't learn—bad language, bad attitude or bad habits. They knew they had backup on the side lines and ran right to him when he pulled them out for more instructions and a pat on the back.

Norman trained his Warriors at his home lot, then brought them to the game so they could show us what they had learned. It is easy to see that "his" parents trained their children in their homes, then released them to play in the game of life, and they have brought dignity to our community. I do not know if he was paid for coaching, but I do know that he did then, and does now, receive gratitude and respect from all the boys that he tutored along the pathway of life. Way to go, Coach!

Roxy

Mr. and Mrs. Everly had a dairy in the days when milking was done by hand. The milk was put through a strainer fitted on top of a 10-gallon milk can. When the can was almost full, Mr. Everly would carry it to the milk house and pour it into a long trough with holes all along the bottom for the milk to leak through and flow down over cooling tubes, then it funneled into another can.

Mrs. Everly would stay in the milk house after that and begin filling quart bottles, capping them with a round cardboard cap. Evening milk was put in a cooler until morning. After morning milking was done, Mr. Everly would deliver the milk to his customers. The customers would set empty bottles on their porches and he would put as many full ones in their place. If the customers wanted more or less, they would put a note in an empty bottle. All extra milk was put through the separator; the cream was taken off the milk and sold to make butter. The skim milk was fed to the pigs and chickens.

Everly's dairy consisted of about 20 cows, mostly crossbreed cows. No two looked alike. They were mixed, Jersey, Guernsey and Holstein breeds. They were spotted brown and white, black and white, gray, brindle and fawn. They had names like Myrtle, Margaret, Flossy, Jewel and Kate—names that made you feel safe. However, there was one cow, Roxy, perhaps "Rocky" would have suited her better. She was average size for her kind, and athletic, alert, aggressive and easily upset when she didn't get her way. "Bossy" would have been another good name for her. When she walked the pasture and back with her friends they gave her lots of space. She kicked out at anyone who crowded her. She also had two very long, sharp, well-shaped horns. Dogs that normally teased cows stayed at a safe distance. Roxy had no markings, which is unusual for dairy cows. She was black as coal.

In those days, calves were separated from their moms when they were three days old. If a farmer didn't want to raise them as replacement cows for the herd, they were sold. The cows got over the separation soon and things returned to normal, except for Roxy. Nothing seemed normal where she was concerned. Roxy never got over being separated. She would rush to the calf barn every time she came from the pasture. Mr. Everly had to drive her back to the milking barn every day. After doing this for a couple of years, he thought he would have to sell her. One day Mrs. Everly said, "We have 20 calves each year; let's let Roxy nurse them as they come along. Then when they are weaned, we will sell them and Roxy will pay her way like that." Mr. Everly agreed. Roxy liked her new role as the nanny for 20 calves a year. Her disposition mellowed and she was more gentle and likable.

Roxy lived to a ripe old cow age and was a friend rather than a foe. As a matter of fact, Shep, the farm dog, slept in the calf barn and Roxy seemed to enjoy having him there.

Morgantown Golf And Country Club

Mr. Albert Spencer hired me to be the lifeguard at the Morgantown Golf and Country Club. The job consisted of taking tickets and looking after the safety of the little children. Also, once a week the water had to be treated with chlorine. Two cans of chlorinated lime were wrapped in a towel and then dragged around the pool until it was dissolved.

The job also carried the title of "all day jobber" at the caddy house, meaning that I could caddy without waiting a turn if it did not interfere with the pool job. Also, I could mow greens in the morning or after 6:00 p.m. when needed.

The pool was 30 feet by 60 feet—one foot deep to nine feet deep. The greens had priority over the pool for the use of water at night, so only a couple of nights a week the water in the pool was raised to overflow so the sun tan oil from the swimmers could be skimmed off.

At the middle of the swimming season around July 15, the pool was drained, scrubbed and refilled to finish the remaining six weeks. The water was so dirty by then you couldn't see a golf ball at four feet deep. Sometimes as many as 100 people would use the pool on a hot day.

During the summer I was called upon three times to pull a child to safety—two boys and one girl. One boy was Rufus Lazzelle, who was pushed into the deep end by a playmate, John Kite. The other was Charles Hayden (later federal judge), who hand-over-hand walked the overflow through the deep end while trying to keep out of the grasp of his mother walking above him telling him to come out and go home. Finally, she made a quick grab for him and he let go and sank to the bottom. He was addled by his action, and when I got to him, he was just standing on the bottom facing the wall with his hands up. The little girl was a guest of the Sam Chico family. She dived off the side of the pool and hit a "belly smacker." It knocked the wind out of her and when she came up for air, she didn't clear the water with her mouth and instead of air she got water in her lungs. It scared her, but after a little coughing and crying she was all right.

I was paid $50.00 a month for five hours, seven days a week. On July 3 that year, the weather was so cold only three people went swimming. On the fourth, no one came, so I cut hedges that circled the clubhouse.

The Morgantown Golf and Country Club was located where the WVU Law School and athletic facilities are now.

Old Man Mallow

In 1942 I was working at the University Dairy Farm on the Mileground after school, weekends and also full time in the summer. It was then I met Abraham Mallow, already nine years past the retirement age of 65. He was still working, as his Social Security was not very big, maybe nonexistent in his case, and because he needed more money.

He was a good man for a boy to be around. He was a man with lots of life experiences. He was also very funny, rather ornery, too, but not vulgar, so I enjoyed the time that I spent working with him.

After I left the farm, he also left—probably forced to retire. He came to our house selling Stark fruit trees. He was still working and then probably 75 or 76 years old. He didn't know where I lived but came to our house purely by chance. I was glad to see him and we bought two apple trees from him. During our visit he asked if some of the neighbors would be good prospects. I could only recommend one, Mrs. Sam Chico Sr. She lived next door, and I knew even if she didn't buy, she would treat him kindly.

Mrs. Chico bought several trees and also bought several grapevines. Abe was very pleased and stopped to tell me about it. The best part was that she hired him to set them in the ground and tend to them by trimming the trees and training the vines.

There is no way to know, but my guess is that Mrs. Chico had never even thought about an orchard in her yard and that she bought from the old man strictly to help him without making him feel like a charity case, for he wouldn't have liked that.

My mother mentioned several times how friendly Mrs. Chico was to her when she would see her walking by.

Being a friendly, caring and good neighbor was not something Mrs. Chico tried to be. She was all of those things because they were the bricks and mortar of which she was made.

Clarence "Grease" Everly

A man formally of Cascade and Masontown named Clarence "Grease" Everly relayed this story to me about 1970. He has long since gone to his reward. It is a story of a happy day in his life when he was a boy.

One day Mr. H. C. Greer came to Cascade and instructed the boss there to round up several boys and have them each lead a pony from Cascade to a mine on Bull Run.

Grease was one of those boys picked for the job. Mr. Greer asked the boss to get the names of all of the boys to him, and he arranged for a time to pick them up and take them to the "Mansion." They got all cleaned up, the best they could. Grease said they washed their hands and faces and combed their hair.

These boys had never been to anything close to the finery of the Mansion. When they were ushered into the big dining room and seated at a big table with platters of fried chicken, they were petrified, afraid to speak or move. After a while Mr. Greer came in and sat down at the head of the table. They all sat in silence. Then Mr. Greer said, "I don't know how you boys like to eat chicken, but I like to eat mine with my hands." Then he reached in and grabbed a piece of chicken and Grease said they all attacked the chicken like it was an enemy. Soon it was gone; the boys were well fed, and a memory was etched in their minds to last a lifetime.

Mr. Greer could have paid the boys 50¢ and they would have thought themselves well paid, but the money would be gone soon with no memory of it to brighten their lives to the end.

Another memory still floated around when I went to work at Greer Limestone in 1967. It was that in the winter, Mr. Greer would occasionally give the M&K train crew a pair of gloves from the company store. There were other memories, but these two give a thumbnail sketch of the kind of man Mr. Greer was. He was in touch with the people who worked for him.

Claude Furman

Communities of times gone by stayed pretty much the same—for years, several generations lived out their lives in the same place. Easton community was such a place. When the name Easton was mentioned to many people, the name Claude Furman came to mind. The reverse was also true. When Claude Furman's name was mentioned, Easton came to mind.

Mr. Furman was not the only man who lived there, but he was one man who was present all day, every day. He was the blacksmith.

There was no chestnut tree spreading over his shop, but Henry Wadsworth Longfellow really knew his subject as he went on to describe the village blacksmith, and as far as I know Claude Furman fit the bill to a T:

The smith a mighty man is he

With large and sinewy hands;

And the muscles in his brawny arms

Are strong as iron bands.

His brow is wet with honest sweat,

He earns what'er he can,

He looks the whole world in the face,

For he owes not any man.

from two stanzas of "The Village Blacksmith"

Certainly Claude Furman did not think of himself as the leader of the band, or the teacher of the school. He lived his life, and all who were acquainted with him could see what integrity, honesty and truth looked like. He was respected because he was respectable.

To illustrate his individuality, I relate a story told to me by Tom Kitzmiller, one of Claude's very dear friends.

Tom sold a horse to a young man to work his mine with. When it needed shod, he brought it to the shop. Tom was there with Mr. Lanham and Fred Reppert. They spent idle time there telling stories of time gone by (a great pastime in those days before TV). The young man walked in leading his horse, threw the lead strap down and said "Put some shoes on him, Pop." Then he joined the others to pass the time. Harry, Claude's son, who fitted the shoes, was tidying up after he shod the horse ahead of his. Claude had not even acknowledged the young man's presence, but just kept working at the forge. After quite a long time, the man said to Tom, "Is he going to shoe my horse or not? Do I have to buy a horse every time it needs shoes?" Tom said he knew the lad was in trouble from the start, and he told him it was his way of talking down to someone, so he said, "I'll talk to 'Mr. Furman' and see if I can fix this mess." So he did and Claude nodded to Harry to go ahead and shoe his horse. Tom told the young man to apologize and from then on to ask Mr. Furman for his services.

Calving And Breeding

All of my life I have wanted to be a farmer. As a little boy I had a different idea about what a farmer was. Mostly it was all of the fun things: searching the farm yard and barn for eggs, getting apples and feeding them to the pigs, riding the horse to bring in hay shocks or plowing corn, picking berries, catching frogs and crawfish, jumping in the hay and many other things. These things were fun because they didn't last long—one day, maybe one hour—but, as time went on I grew and became useful to do some work. My uncle, James Gorman, used me and my brother John for various jobs. John was three years older and more useful. When I was 11 years old I went to my uncle's farm by myself.

While I was there, without explaining what we were about to do, he untied his Holstein cow, left the rope around her neck. brought her out, handed me the end of the rope and we started down the driveway. When we got to Chestnut Ridge Road the cow took flight running as fast as she could, then she would stop dead still, practically tossing me over her head. She would eat a little grass along the road, then off again like a shot, then stop, and then start. I was beginning to become leery of her; always before she was very docile and tame, now she was wild and scary. We reached the Van Voorhis Road and she turned left toward town. By then Uncle Jim, who was crippled and old, was far behind. It was just the cow and me, and I was beginning to be afraid. Out the road toward town we flew, me thinking we would go into town and wondering what I should do. I did not realize that the cow knew exactly what she was doing. It was her time; she was making a social call on her "gentleman cow," the bull at the county farm.

The cow turned left at Drummond Chapel Church and ran up the hospital drive to the gate that led to the bull pen of the county farm. She stopped, heaving and blowing like a racehorse after a race and me still with her, trembling and sweating, relieved that she had stopped. A man came and took the rope from me, and we waited for Uncle Jim, for he was still far back. When he came, he and the county man went in the gate. He told me to go and sit away back and wait for him. I went back but after they were gone from sight, I sneaked up to a large shrub where I could see what was going on.

The man went into the barn, led a bull out with a long stick hooked in his nose ring. The bull mounted the cow, bred her and the man took him back. I scrambled back to my place and thus I witnessed for the first time a cow being bred. Now we had to get home. The cow was a little more settled as we proceeded out the road; however, they let the bull loose and he ran the fence until he saw us going. He bellowed, the cow jerked away from me and went back. I knew I would not be able to lead her away from him, and I was afraid he might come over the fence. Luckily, the dogcatcher came by. He jumped out, grabbed the cow's rope, tied it to his truck and led her a ways down the road. When he thought it was far enough, he stopped, gave me the rope and watched me for a while to be sure I would get along, which I did. When I turned up the driveway and led the cow back to the barn I was greatly relieved. Uncle Jim came along afterward and gave me a dime. I was beginning to see in earnest what farming was all about.