Roman Catholic Church

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

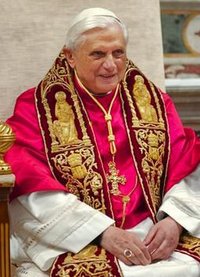

The Catholic Church, known also as the Roman Catholic Church, is the Christian Church whose visible head is the Pope, currently Benedict XVI.

It teaches that it is the "one holy catholic and apostolic Church founded by Jesus Christ," and that "the sole Church of Christ which in the Creed we profess to be one, holy, catholic and apostolic" has a concrete realization "in the Catholic Church, which is governed by the successor of Peter and by the bishops in communion with him" (The Second Vatican Council's Decree on the Church, Lumen Gentium, 8).[1] The term "successor of Peter" refers to the Bishop of Rome, the Pope. The phrase "governed by the successor of Peter and by the bishops in communion with him" thus defines the Catholic Church's visible identity.

It has a membership of over one billion people. The figure in the 2003 Statistical Yearbook of the Church, based on the statistical reports that Catholic dioceses throughout the world sent in about the situation on 31 December of that year, is 1,085,557,000; because of obstacles to regular contacts, this figure does not include Catholics in mainland China and perhaps in some other places. According to canon law, members are those who have been baptized in the Catholic Church or have been received into the Catholic Church after being baptized elsewhere, and who have not formally renounced membership.

Worldwide, the Church is divided into jurisdictional areas, usually on a territorial rather than a personal basis. The typical form of these is what is usually called in the West a diocese, in the East an eparchy, headed by a bishop or eparch known in the West as the Ordinary (because he has "ordinary", not delegated, authority) and in the East as the Hierarch. Some of these areas have the rank of archdiocese or archeparchy, and are headed by an archbishop or archeparch, who, if he has a certain limited jurisdiction over the other dioceses of the same ecclesiastical province, is known as the metropolitan. The word "see", derived from Latin sedes, (a bishop's) chair, is applied generically to all of these. Other jurisdictional areas are territorial prelatures, territorial abbacies, apostolic exarchates and ordinariates for Eastern-rite faithful, military ordinariates, personal prelatures (of which only one exists at present), apostolic vicariates, apostolic prefectures, apostolic administrations, and autonomous missions. At the end of 2004, the total number of all these jurisdictional areas was 2755 (Annuario Pontificio 2005).

The see of Rome is seen as central, and its bishop, the Pope, is considered to be the successor of Saint Peter, the chief of the Apostles, sometimes called the "prince" (from Latin princeps, meaning "foremost", "leader") of the Apostles.

Overview

Members of the Catholic Church believe that the Church was instituted by Jesus Christ for the salvation of souls, and that this is accomplished through teaching and administering the sacraments - including Baptism, Eucharist, and Penance (forgiveness of sins, also called "Confession") - means by which God grants grace. It bases its teachings on both Scripture and Apostolic Tradition. It is a hierarchical organization headed by the Pope, with ordained clergy divided into the orders of bishops, priests, and deacons. The Church also encourages monasticism, and has many religious institutes of monks, friars, nuns, and others who live in celibacy and devote their lives entirely to God. Other religious practices for clergy, religious and laity alike include fasting, prayer, penance, pilgrimage and meditation.

According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, the Church's first purpose is "to be the sacrament of the inner union of men with God." Thus the Church's "structure is totally ordered to the holiness of Christ's members." (Catechism of the Catholic Church 775, 773).

Terminology

Roman Catholic Church is the term most often, though not exclusively, used for this Church by other Christian Churches, especially in English-speaking Protestant-influenced countries. While the Church itself accepts this description in its relations with other Churches, Catholic Church is the designation it normally uses. Nevertheless, because of the centrality of the see of Rome, it has, even in internal documents, sometimes applied the adjective "Roman" to itself in its entirety, as when, at the start of chapter 1 of the First Vatican Council's Dogmatic Constitution on the Catholic Faith,[2] it described itself as the "Holy, Catholic, Apostolic and Roman Church". (This is only one of many self-descriptions that the Roman Catholic Church has used. Others include "Mystical Body of Christ", "People of God", "universal sacrament of salvation" (cf. Catechism of the Catholic Church, 748-810.)

Divergent usages attach a certain ambiguity to each of these terms. For some, the term "Roman Catholic Church" refers only to the Western or Latin Church, excluding the Eastern-Rite particular Churches in full communion with the Pope, which therefore are part of the same Church taken as a whole. As for "Catholic Church", there are other claimants to the name; for the meanings they attribute to the term, see Catholicism.

Without intending to make any judgement on which is the correct term, "Roman Catholic Church" and "Catholic Church" will be treated within this article as alternative names for the entire Church "which is governed by the successor of Peter and by the bishops in communion with him".

It has been remarked that what St Augustine (354-430) wrote in 397 still holds in the twenty-first century for common practice, even among those who in formal discourse insist on using "Roman Catholic Church". Note that in Augustine's time Christians applied the word "priest" to bishops, but not to the lower rank of clergy that are today called "priests" in English. The "seat of the Apostle Peter" is, of course, the see of Rome.

In the Catholic Church ... there are many other things which most justly keep me in her bosom. The consent of peoples and nations keeps me in the Church; so does her authority, inaugurated by miracles, nourished by hope, enlarged by love, established by age. The succession of priests keeps me, beginning from the very seat of the Apostle Peter, to whom the Lord, after His resurrection, gave it in charge to feed His sheep (John 21:15-19), down to the present episcopate. And so, lastly, does the very name of Catholic, which, not without reason, amid so many heresies, the Church has thus retained; so that, though all heretics wish to be called Catholics, yet when a stranger asks where the Catholic Church meets, no heretic will venture to point to his own chapel or house.

- — Against the Epistle of Manichaeus called Fundamental, chapter 4: Proofs of the Catholic Faith[3]

Beliefs

The Nicene Creed and the Apostles Creed are the most succinct statements of what the Catholic Church believes; the most elaborate statement is found in the recent (1992) Catechism of the Catholic Church.

The nature of God

Lex orandi lex credendi is a traditional Latin phrase to the effect that our belief shows in the way we pray. So the Catholic Church's theology, like its liturgy, is Trinitarian. A Catholic Christian is baptized in the name (singular) of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit - not three gods, but One God in three persons. The faith of the Church and of the individual Christian is based on a relationship with these three Persons of the one God.

The Catholic Church believes that God has revealed himself to humanity as Father to one Son who is in an eternal relationship with the Father: "No one knows the Son except the Father, just as no one knows the Father except the Son and those to whom the Son chooses to reveal him" (Matthew 11:27).

Catholics believe that God the Word, one of the three persons of God, became incarnate as Jesus Christ, a human being, born of the Virgin Mary. He remained truly divine and at the same time truly human. In what he said, and by how He lived, He taught us how to live, and revealed God as love, the giver of unmerited favours or Graces.

After Jesus' crucifixion and resurrection, his followers, foremost among them the Apostles, spread more and more extensively their faith in Jesus Christ with a vigour that they attributed to the Holy Spirit sent upon them by Jesus.

Humanity's separation from God

Human beings, in Catholic belief, were originally created perfect, to live in union with God and all creation. However, through disobedience to God, the first humans broke that unity and introduced sin and death into the world (cf. Romans, 5:12). Man's Fall left him condemned, when he died, to remain eternally separate from God. But when Jesus came into the world, as both God and man, He was able through His sacrifice to pay the penalty for the sins of men and to reconcile the human with the Divine. By becoming One in Christ, through the Church, humanity was once again capable of participation in the Divine Life, called also the Beatific Vision.

The role of the Church

Catholics believe that Jesus established only one Church, not many, and that that Church is truly, though of course not physically, the Body of Christ, made up of members both on earth and in heaven. They believe that Jesus chose the Apostle Peter to lead the Church, that Peter went to Rome and became bishop of the Church there, and that Peter's authority was subsequently passed on to the successive bishops of Rome. The one true Church therefore consists of those who follow Jesus and who recognise the religious authority of Peter in his current successor, popularly called the Pope.

Catholics believe that Jesus has promised that the Church on earth will always be guided and maintained in truth by the Holy Spirit. In other words, the Church will always and infallibly teach true doctrine. This truth is contained both in the written Scriptures and the oral traditions passed down through the Church. The written Scriptures arose within a Church that handed on true doctrine orally, and can be properly understood only in the light of the Church's living tradition. There can be no contradiction between these two ways in which the "deposit of faith" (from Latin depositum, something entrusted, cf. 1 Timothy 6:20) is guarded and handed down, so that no Catholic belief or practice can contradict the Sacred Scriptures.

Magisterium

The Catechism of the Catholic Church, 85 states that authentic interpretation of the Word of God is entrusted to the living Magisterium of the Church, namely the bishops in communion with the successor of Peter. Catholic theology places the authoritative interpretation of scripture in the hands of the corporate judgment of the Church rather than the private judgment of the individual.

Salvation

The Church teaches that salvation to eternal life is God's will for all people, and that God grants it to sinners as a free gift, a grace, through the sacrifice of Christ. Man cannot, in the strict sense, merit anything from God (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2007). It is God who justifies, that is, who frees from sin by a free gift of holiness (sanctifying grace, also known as habitual or deifying grace). Man can accept the gift God gives through faith in Jesus Christ (Romans 3:22) and through baptism (Romans 6:3-4). Man can also refuse the gift. Human cooperation is needed, in line with a new capacity to adhere to the divine will that God provides (cf. Response of the Catholic Church to the Joint Declaration of the Catholic Church and the Lutheran World Federation on the Doctrine of Justification, 2-3).[4] The faith of a Christian is not without works, otherwise it would be dead (cf. James 2:26). In this sense, "by works a man is justified, and not only by faith" (James 2:24), and eternal life is, at one and the same time, grace and the reward given by God for good works and merits. See Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1987-2016.

The Christian Path

Following baptism, the Catholic Christian must endeavour to be a true disciple of Jesus. The believer must seek forgiveness of subsequent sins, and try to follow the example and teaching of Jesus. To help Christians, Jesus has provided seven sacraments which give Grace from God to the believer. These are, Baptism, Confirmation, Eucharist, Reconciliation/Confession, Anointing of the Sick, Holy Orders, and Matrimony.

Catholics believe that God works actively in the world. Christians may grow in grace through prayer, good works, and spiritual disciplines such as fasting and pilgrimage. Prayer takes the form of praise, thanksgiving and supplication. Christians can and should pray for others, even for enemies and persecutors (Matthew 5:44). They may address their requests for the intercession of others not only to people still in earthly life, but also to those in heaven, in particular the Virgin Mary and the other Saints. As Mother of Jesus, the Virgin Mary is also considered to be the spiritual mother of all Christians. Unless a Christian dies in unrepented mortal sin, which is normally remitted in Penance, that person has God's promise of inheriting eternal life. Before entering heaven, some undergo a purification, known as Purgatory. Catholic teachings include a stress on forgiveness, doing good to others, and on the sanctity of life, opposing euthanasia, eugenics, contraception and abortion, which can destroy divinely created life.

The Catholic Church maintains that, through the graces Jesus won for humanity by sacrificing himself on the cross, salvation is possible even for those outside the visible boundaries of the Church, whether non-Catholic Christians or non-Christians, if in life they respond positively to the grace and truth that God reveals to them. This may sometimes include awareness of an obligation to become part of the Catholic Church. In such cases, "they could not be saved who, knowing that the Catholic Church was founded as necessary by God through Christ, would refuse either to enter it, or to remain in it" (Second Vatican Council: Dogmatic Constitution Lumen gentium, 14).

Social teaching

- Main article: Catholic social teaching

The Church holds that the teachings of Jesus call on its members to act in a particular way in their dealings with the rest of humanity. While not endorsing any particular political agenda, the Church holds that this teaching applies in the public (political) realm, not only the private. Among these teachings, as they have been elaborated in recent decades by Catholic thinkers, Bishops' statements and Papal encyclicals, are that every person has a right to life and to a decent minimum standard of living, that humanity's use of God's creation implies a responsibility to protect the environment, and that the range of circumstances under which military force is permissible is extremely limited.

Liturgy

The Catholic Church sees the liturgy, the celebration of the Mystery of Christ, in particular the Paschal Mystery of his death and resurrection, as the high point of its activity and the source of its life and strength.

As explained in greater detail in the Catechism of the Catholic Church and its shorter Compendium, the liturgy is something that "the whole Christ", Head and Body, celebrates - Christ, the one High Priest, together with his Body, the Church in heaven and on earth. Involved in the heavenly liturgy are the angels and the saints of the Old Covenant and the New, in particular Mary, the Mother of God, the Apostles, the Martyrs and "a great multitude, which no man could number, out of every nation and of all tribes and peoples and tongues" (Revelation 7:9). The Church on earth, "a royal priesthood" (1 Peter 2:9), celebrates the liturgy in union with these: the baptized offering themselves as a spiritual sacrifice, the ordained ministers celebrating at the service of all the members of the Church in accordance with the order received, and bishops and priests acting in the person of Christ.

The Christian liturgy uses signs and symbols whose significance, based on nature or culture, has been made more precise through Old Testament events and has been fully revealed in the person and life of Christ. Some of these signs and symbols come from the world of creation (light, water, fire, bread, wine, oil), others from life in society (washing, anointing, breaking bread), others from Old Testament sacred history (the Passover rite, sacrifices, laying on of hands, consecrating persons and objects).

In the Christian liturgy these signs are closely linked with words. Though in a sense the signs speak for themselves, they need to be accompanied and vivified by the spoken word. Taken together, word and action indicate what the rite signifies and effects.

Singing and music are associated with the liturgy. So also are sacred images, which proclaim the same message as do the words of Sacred Scripture and which help to awaken and nourish faith.

The most important parts of the liturgy are the sacraments, instituted by Christ (see below).

In addition there are many sacramentals, sacred signs (rituals or objects) instituted by the Church (rather than by Christ) that derive their power from the prayer of the Church. They involve prayer accompanied by the sign of the cross or other signs. Important examples are blessings (by which praise is given to God and his gifts are prayed for), consecrations of persons, and dedications of objects to the worship of God.

Popular devotions are not strictly part of the liturgy, but if they are judged to be authentic, the Church encourages them. They include veneration of relics of saints, visits to sacred shrines, pilgrimages, processions, the Stations of the Cross (also known as the Way of the Cross), and the Rosary.

Sunday, which commemorates the resurrection of Christ and has been celebrated by Christians from the earliest times (1 Corinthians 16:2; Revelation 1:10; Ignatius of Antioch: Magn.9:1; Justin Martyr: I Apology 67:5), is the outstanding occasion for the liturgy; but no day, not even any hour, is excluded from celebrating the liturgy.

The Liturgy of the Hours consecrates to God the whole course of day and night. Lauds and Vespers (morning and evening prayer) are the principal hours. To these are added one or three intermediate prayer periods (traditionally called Terce, Sext and None), another prayer period to end the day (Compline), and a special prayer period called the Office of Readings (formerly known as Matins) at no fixed time, devoted chiefly to readings from the Scriptures and ecclesiastical writers. The Second Vatican Council suppressed an additional 'hour' called Prime. The prayers of the Liturgy of the Hours consist principally of the Psalter or Book of Psalms. Like the Mass, the Liturgy of the Hours has inspired great musical compositions. An earlier name for the Liturgy of the Hours and for the books that contained the texts was the Divine Office (a name still used as the title of one English translation), the Book of Hours, and the Breviary. Bishops, priests, deacons and members of religious institutes are obliged to pray at least some parts of the Liturgy of the Hours daily, an obligation that applied also to subdeacons.

New Testament worship "in spirit and in truth" (John 4:24) is not linked exclusively with any particular place or places, since Christ is seen as the true temple of God, and through him Christians too and the whole Church become, under the influence of the Holy Spirit, a temple of God (1 Corinthians 3:16). Nevertheless the earthly condition of the Church on earth makes it necessary to have certain places in which to celebrate the liturgy. Within these churches, chapels and oratories, Catholics put particular emphasis on the altar, the tabernacle, the place in which chrism and other holy oils are kept, the seat of the bishop or priest and the baptismal font.

The richness of the Mystery of Christ cannot be exhausted by any one liturgical tradition and has from the beginning found varied complementary expressions characteristic of different peoples and cultures. As catholic or universal, the Church believes it can and should hold within its unity the true riches of these peoples and cultures.

There are in the liturgy, specifically in the sacraments, elements that cannot be changed, because they are of divine institution. These the Church must guard carefully. Other elements may be changed, and the Church has the power, and sometimes the duty, to adapt them to the different cultures of peoples and times.

Sacraments

The Catholic Church, like other ancient Christian Churches such as the Eastern Orthodox Church, recognizes and administers seven sacraments as gifts from Christ to his Church. These signs perceptible to the senses are seen as means by which Christ gives the particular grace indicated by the sign aspect of the sacrament in question, helping the individual to advance in holiness, and contributing to the Church' s growth in charity and in giving witness. Not every individual receives every sacrament, but the Church sees the sacraments as necessary means of salvation, conferring each sacrament' s special graces, forgiveness of sins, adoption as children of God, conformation to Christ, and membership of the Church. The effect of the sacraments comes ex opere operato (by the very fact of being administered): through them, regardless of the minister' s personal holiness, Christ provides the graces of which they are signs. However, a recipient' s own lack of proper dispositions can block their effectiveness in that person. The sacraments presuppose faith; and, in addition, their words and ritual elements nourish, strengthen and give expression to faith.

List of the seven sacraments, with references to the sections of the Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC) that deal with each:

- Baptism: CCC 1213-1284

- Confirmation (Byzantine Catholics prefer the term Chrismation in English, similar to the term universally used in the Italian language): CCC1285-1321

- Eucharist: CCC 1322-1419

- Reconciliation and Penance (Confession): CCC 1422-1498

- Anointing of the Sick (formerly called Extreme Unction): CCC 1499-1532

- Holy Orders: CCC 1536-1600

- Matrimony: CCC 1601-1666

What follows is an account, again largely based on the Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, of how the Catholic Church views each of these sacraments.

Baptism is the first and basic sacrament of Christian initiation. It is administered by immersing the recipient in water or by pouring (not just sprinkling) water on the person's head "in the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit" (cf. Matthew 28:19). The ordinary minister of the sacrament is a bishop or priest, or (in the Western Church, but not in the Eastern Churches) a deacon. In case of necessity, anyone intending to do what the Church does, even if that person is not a Christian, can baptize. Baptism frees from original sin and all personal sins and from the punishment due to them, and makes the baptized person share in the Trinitarian life of God through "sanctifying grace" (the grace of justification that incorporates the person in Christ and his Church). It makes the person a sharer too in the priesthood of Christ and is the foundation of communion between all Christians. It imparts the "theological" virtues (faith, hope and charity) and the gifts of the Holy Spirit. It marks the baptized person with a spiritual seal or character that indicates permanent belonging to Christ.

Confirmation or Chrismation is the second sacrament of Christian initiation. It is conferred by anointing with chrism, an oil into which balm has been mixed, giving it a special perfume, together with a special prayer that refers, in both its Western and Eastern variants, to a gift of the Holy Spirit that marks the recipient as with a seal. Through the sacrament the grace given in baptism is "strengthened and deepened" (Catechism of the Catholic Church §1303). Like baptism, confirmation may be received only once, and the recipient must be in a state of grace (meaning free from any known unconfessed mortal sin) in order to receive its effects. The "originating" minister of the sacrament is a validly consecrated bishop; if a priest (a "presbyter") confers the sacrament - as is done ordinarily in the Eastern Churches and in special cases in the Latin-Rite Church (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1312-1313) - the link with the higher order is indicated by the use of oil blessed by a bishop. In the East the sacrament is administered immediately after baptism. In the West administration came to be postponed until the recipient's early adulthood; but in view of the earlier age at which children are now admitted to reception of the Eucharist, it is more and more restored to the traditional order and administered before giving the third sacrament of Christian initiation.

The Eucharist is the sacrament (the third of Christian initiation) by which Catholics partake of the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ and participate in his one sacrifice. The first of these two aspects of the sacrament is also called Holy Communion. The bread and wine used in the rite are, in Catholic faith, considered to be transformed in all but appearance into the Body and Blood of Christ, a change that is commonly called transubstantiation. Only a priest is enabled to be a minister of the Eucharist, acting in the person of Christ himself. Deacons as well as priests are ordinary ministers of Holy Communion, and lay people may be authorized to act as extraordinary ministers of Holy Communion. The Eucharist is seen as "the source and summit" of Christian living, the high point of God 's sanctifying action on the faithful and of their worship of God, the point of contact between them and the liturgy of heaven. So important is it that participation in the Eucharistic celebration (see Mass (liturgy)) is seen as obligatory on every Sunday and holy day of obligation and is recommended on other days. Also recommended for those who participate in the Mass is reception, with the proper dispositions, of Holy Communion. This is seen as obligatory at least once a year, during Eastertide.

Penance and Reconciliation are names given to the first of two sacraments of healing, which is also called the sacrament of conversion, of confession, and of forgiveness (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1423-1424).[5] It is the sacrament of spiritual healing of a baptized person from the distancing from God involved in sins committed. It involves four elements: the penitent's contrition for sin (without which the rite does not have its effect), confession to a priest (it may be spiritually helpful to confess to another, but only a priest has the power to administer the sacrament), absolution by the priest, and satisfaction. In early Christian centuries, the fourth element was quite onerous and generally preceded absolution, but now it usually involves a simple task (in some traditions called a “penance”) for the penitent to perform, to make some reparation and as a medicinal means of strengthening against further temptation.

Anointing of the Sick is the second sacrament of healing. In it a priest anoints with oil blessed specifically for that purpose those who because of sickness or old age are in incipient danger of dying. A worsening of their health enables them to receive the sacrament a further time. When, in the Western Church, the sacrament was conferred only on those in immediate danger of death, it came to be known as "Extreme Unction", i.e. "Final Anointing", being conferred as one of the "Last Rites". The other "Last Rites" are Confession (if the dying person is physically unable to confess, at least absolution, conditional on the existence of contrition, is given), and the Eucharist, which when administered to the dying is known as "Viaticum", a word whose original meaning in Latin was "provision for a journey".

Holy Orders is the sacrament by which one becomes a bishop, a priest or a deacon. Only a bishop may administer this sacrament. Ordination as a bishop confers the fulness of the sacrament, making the bishop a member of the body that has succeeded to that of the Apostles, and giving him the mission to teach, sanctify and guide, along with the care of all the Churches. Ordination as a priest configures the priest to Christ the Head of the Church and the one essential Priest, empowering him, as the bishops' assistant, to celebrate divine worship, especially the Eucharist. Ordination as a deacon configures the deacon to Christ the Servant of All, placing him at the service of the Church, especially in the fields of the ministry of the word, divine worship, pastoral guidance and charity. (On "minor orders", see below, under the heading "Priests and deacons".)

Matrimony, or Marriage, is, like Holy Orders, a sacrament that consecrates for a particular mission in building up the Church, and that provides grace for accomplishing that mission. This sacrament, seen as a sign of the love uniting Christ and the Church, establishes between the spouses a permanent and exclusive bond, sealed by God. Accordingly, a marriage between baptized persons, validly entered into and consummated, cannot be dissolved. The sacrament confers on them the grace they need for attaining holiness in their married life and for responsible acceptance and upbringing of their children. The sacrament is celebrated as a public ceremony in the presence of the priest (or another witness appointed by the Church) and other witnesses. For a valid marriage, a man and a woman must express their conscious and free consent to a definitive self-giving to the other, excluding none of the essential properties and aims of marriage. If one of the two is a non-Catholic Christian, their marriage is licit only if the permission of the competent authority of the Catholic Church is obtained. If one of the two is not a Christian (i.e. has not been baptized) this permission is necessary for validity.

Relations with other Christians

The Roman Catholic Church attributes very high authority to 21 Ecumenical Councils: Nicaea I (325), Constantinople I (381), Ephesus (431), Chalcedon (451), Constantinople II (553), Constantinople III (680-681), Nicaea II (787), Constantinople IV (869-870), Lateran I (1123), Lateran II (1139), Lateran III (1179), Lateran IV (1215), Lyons I (1245), Lyons II (1274), Vienne (1311-1312), Constance (1414-1418), Florence (1438-1445), Lateran V (1512-1517), Trent (1545-1563), Vatican I (1869-1870), Vatican II (1962-1965).

Of these, the Orthodox Churches of Byzantine tradition accept only the first seven, the family of "non-Chalcedonian" or "pre-Chalcedonian" Churches only the first three, and the Christians of Nestorian tradition only the first two.

Dialogue has shown that even where the break with one of these ancient Churches occurred as far back as the Councils of Ephesus (431) and Chalcedon (451), long before the break with Constantinople (1054), the few doctrinal differences often concern terminology, not substance.

Emblematic is the "Common Christological Declaration between the Catholic Church and the Assyrian Church of the East" [6] (note the less common but by no means unique use in an inter-Church document of "Catholic Church" rather than "Roman Catholic Church"), signed by "His Holiness John Paul II, Bishop of Rome and Pope of the Catholic Church, and His Holiness Mar Dinkha IV, Catholicos-Patriarch of the Assyrian Church of the East", on 11 November 1994. The division between the two Churches in question goes back to the disputes over the legitimacy of the expression "Mother of God" (as well as "Mother of Christ") for the Virgin Mary that came to a head at the Council of Ephesus in 431. The Common Declaration recalls that the Assyrian Church of the East prays the Virgin Mary as "the Mother of Christ our God and Saviour", and the Catholic tradition addresses the Virgin Mary as "the Mother of God" and also as "the Mother of Christ", fuller expressions by which each Church clearly acknowledges both the divinity and the humanity of Mary's son. The co-signers of the Common Declaration could thus state: "We both recognize the legitimacy and rightness of these expressions of the same faith and we both respect the preference of each Church in her liturgical life and piety."

Some, at least, of the most difficult questions in relations with the ancient Eastern Churches concern not so much doctrine as practical matters such as the concrete exercise of the claim to papal primacy and how to ensure that ecclesial union would not mean mere absorption of the smaller Churches by the Latin component of the much larger Roman Catholic Church (the most numerous single religious denomination in the world), and the stifling or abandonment of their own rich theological, liturgical and cultural heritage.

There are much greater differences with the doctrinal views of Protestants, who Catholics feel have broken continuity with the past, while Protestants claim that, if they have done so, it was for the sake of fidelity to what they believe to be the true teaching of the apostles. But even with these groups, dialogue has on both sides clarified some misunderstandings of what the other believes.

Particular Churches within the single Catholic Church

Unlike "families" or "communions" of Churches that see themselves as distinct Churches, the Church of those who are in full communion with the Pope considers itself a single Church, not a federation of Churches. It has authoritatively expressed this self-understanding in, for instance, the 28 May 1992 Letter to the Bishops of the Catholic Church on some aspects of the Church understood as communion, 9.[7]

Accordingly, it has never adopted the usage of those who apply the term "Roman Catholic" to the Latin-Rite or Western Church alone, to the exclusion of the Eastern Churches that also are in full communion with the Bishop of Rome. When it employs the term "Roman Catholic Church", which it rarely does except in its relations with other Churches, it means the whole Church "governed by the successor of Peter and by the bishops in communion with him", wherever they live and whether they are of Eastern or Western tradition, the whole Church that has as its central point of reference Rome, whose Bishop the Church sees as the successor of Saint Peter. The only other meaning it would give to "Roman Catholic" is "a Catholic who lives in Rome", as a Catholic who lives in Warsaw could be called a Warsaw Catholic.

On the other hand, the Roman Catholic Church attaches great importance to the particular Churches within it, whose theological significance the Second Vatican Council highlighted. Two categories of particular Churches are distinguished.

Particular Churches or rites

The higher level of particular Churches is that of what the Second Vatican Council’s Decree on the Catholic Eastern Churches Orientalium Ecclesiarum, 2[8] calls "particular Churches or rites". The long-established use of the term "rite" for these particular Churches is due to the central place that the Eucharist holds in the Roman Catholic Church, making each particular Church's liturgy its most noted distinguishing mark.

However, the word "rite" is used not only of particular Churches but also of liturgical rites. While the Eastern Orthodox Churches have, with scarcely any variation except for language, a single uniform liturgical rite, known, because of the city where it originated, as the Byzantine rite, the Catholic Church uses a great variety of liturgical rites.

Not only the term "rite", but also, as we shall soon see, the term "particular Church" can be understood in more than one way. Since a legal text must be careful to avoid ambiguities, the 1983 Code of Canon Law adopted instead the term "autonomous ritual Church" (in Latin, "Ecclesia ritualis sui iuris") for the reality that the Second Vatican Council called a "particular Church or rite"; and the 1990 Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches shortened this to "autonomous Church" (in Latin, "Ecclesia sui iuris").

The autonomy of each such Church, Eastern or Western, shows in its distinctive liturgy, canon law, theological tradition, etc. The Latin or Western particular Church is governed by the Code of Canon Law, while the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches outlines the discipline that the Eastern particular Churches have in common.

The official yearly Vatican directory, Annuario Pontificio (Libreria Editrice Vaticana), gives the following list of rites (in the sense of particular Churches, not of liturgical rites) within the Roman Catholic Church

Eastern rites (particular Churches)

- Alexandrian tradition

- Antiochian (or Antiochene) tradition

- Armenian tradition: Armenian Church

- Byzantine (Constantinopolitan) tradition:

- Albanian

- Belarusian

- Bulgarian

- Greek

- Greek-Melkite

- Hungarian

- Italo-Albanian

- Romanian

- Russian

- Ruthenian

- Slovak

- Ukrainian

Western rite (particular Church)

It is argued that this official list should be updated by adding the following five particular Churches, all of Byzantine tradition:

Note on liturgical rites in use within the Western (Latin) Church

For many centuries there were as many or more liturgical rites in the western Catholic Church or Latin Rite, as in the East. The Council of Trent suppressed those that could not be shown to have an antiquity of at least two centuries. Many that remained legitimate even after this decree were abandoned voluntarily, a process that continued into the second half of the twentieth century. A few persist today for the celebration of Mass, but the distinct liturgical rites for celebrating the other sacraments have been almost completely abandoned.

The following liturgical rites have been in use at some time within the Latin particular Church:

- The Roman rite. Like other liturgical rites, this developed over the centuries. The form of its Mass liturgy that was codified in the wake of the Council of Trent and that underwent only minor modifications until Pope Pius XII revised the part dealing with the days from Holy Thursday to the Easter Vigil in 1955 and Pope Paul VI made a general revision of the whole Roman Missal in 1970 (see Novus Ordo Missae)is often referred to as the Tridentine Mass. Traditionalist Catholics claim that the liturgical reforms of the rites of the Mass and the other sacraments after the Second Vatican Council marked a complete break rather than a further development (like those that occurred in the Roman liturgical rite during the first millennium and a half of its existence) and speak of a distinct "Tridentine rite".

- The Ambrosian rite celebrated throughout the Archdiocese of Milan, Italy.

- The Mozarabic rite celebrated in the cathedral of Toledo and once prevalent throughout Spain.

- The Anglican Use rite is for use by Anglican priests who enter into full communion with the Catholic Church and continue their ministry.

- The Braga rite once celebrated in Portugal.

- The rites particular to religious orders (e.g. Dominicans, Carthusians, and Carmelites).

- The Sarum Rite and the York Use of the dioceses of Salisbury and York in Pre-Reformation England, respectively.

- The Celtic rites of Ireland and northern Britain (including Scotland), replaced by the Roman rite in the Middle Ages.

- The Gallican rite that, even after the Council of Trent, enjoyed currency in France in the period before the French Revolution and for some time after.

- The Lyonnais rite of Lyon, France is a relic of this rite.

- The Trondheim rite used in pre-Reformation Norway.

- The African rite used in North Africa prior to the Arab conquest (8th century), of which practically no details are known.

None of the still surviving liturgical rites in this list is a "particular Church or rite" in the sense considered here. A "particular Church or rite" does not necessarily use a distinct liturgical rite: many Eastern Catholic Churches all use the same Byzantine liturgical rite. And an individual "particular Church or rite" may use several distinct liturgical rites: the Latin-Rite Church uses several liturgical rites, even apart from the alleged distinction between a "Tridentine" and a "Second Vatican Council" rite.

Particular or local Churches

In Catholic teaching, each diocese too is a local or particular Church: "A diocese is a section of the People of God entrusted to a bishop to be guided by him with the assistance of his clergy so that, loyal to its pastor and formed by him into one community in the Holy Spirit through the Gospel and the Eucharist, it constitutes one particular church in which the one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church of Christ is truly present and active" (Second Vatican Council, Decree on the Pastoral Office of Bishops in the Church Christus Dominus, 11[9]).

Theological significance

The particular Churches within the Catholic Church, whether rites or dioceses, are seen as not simply branches or sections of a larger body. Theologically, each is considered to be the embodiment in a particular place of the whole Roman Catholic Church. "It is in these and formed out of them that the one and unique Catholic Church exists" (Second Vatican Council, Dogmatic Decree on the Church Lumen Gentium, 23.[10]).

The hierarchical constitution of the Church

The Pope

What most obviously distinguishes the Roman Catholic Church from others is the link between its members and the Pope. The Catechism of the Catholic Church, 882, quoting the Second Vatican Council’s document Lumen Gentium, states: "The Pope, Bishop of Rome and Peter’s successor, ‘is the perpetual and visible source and foundation of the unity both of the bishops and of the whole company of the faithful.’"[11]

The Pope is referred to as the Vicar of Christ and the Supreme Pontiff of the Universal Church. Applying to him the term "absolute" would, however, give a false impression: he is not free (the word "absolute" etymologically means "loosed") to issue decrees at whim. Instead, his charge forces on him awareness that he, even more than other bishops, is "tied", bound, by an obligation of strictest fidelity to the teaching transmitted down the centuries in increasingly developed form within the Roman Catholic Church.

In certain circumstances, this papal primacy, which is referred to also as the Pope's Petrine authority or function, involves papal infallibility, i.e. the definitive character of the teaching on matters of faith and morals that he propounds solemnly as visible head of the Church. In any normal circumstances, exercise of this authority will involve previous consultation of all Catholic bishops.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church, 891 says: "’The Roman Pontiff, head of the college of bishops, enjoys this infallibility in virtue of his office, when, as supreme pastor and teacher of all the faithful – who confirms his brethren in the faith – he proclaims by a definitive act a doctrine pertaining to faith or morals... The infallibility promised to the Church is also present in the body of bishops when, together with Peter’s successor, they exercise the supreme Magisterium,’ above all in an Ecumenical Council."[12]

These are two ways, the Catechism of the Catholic Church, 890 states, in which the pastors of the Church exercise the charism of infallibility with which Christ has endowed them for the purpose of guarding from deviation and decay the authentic faith of the definitive covenant that God has established in Christ with his people. In other words, they are two ways of ensuring that "the gates of Hell will not prevail" (Matthew 16:18) against the Church.

The Pope lives in Vatican City, set up in 1929 as a tiny, but symbolically important, independent state within the city of Rome. The body of officials that assist him in governance of the Church as a whole is known as the Roman curia. The term "Holy See" (i.e. of Rome) is generally used only of Pope and curia, because the Code of Canon Law, which concerns governance of the Latin Church as a whole and not internal affairs of the see (diocese) of Rome itself, necessarily uses the term in this technical sense.

The present rules governing the election of a pope are found in the apostolic constitution Universi Dominici Gregis.[13] This deals with the powers, from the death of a pope to the announcement of his successor’s election, of the cardinals and the departments of the Roman curia; with the funeral arrangements for the dead pope; and with the place, time and manner of voting of the meeting of the cardinal electors, a meeting known as a conclave. This word is derived from Latin com- (together) and clavis (key) and refers to the locking away of the participants from outside influences, a measure that was introduced first as a means instead of forcing them to reach a decision.

A pope has the option of resigning. (The term "abdicate" is not normally used of popes.) The two best known cases are those of Pope Celestine V in 1294 (who, though the poet Dante Alighieri pictured him condemned to hell for this action, was canonized in 1313) and Pope Gregory XII, who resigned in 1415 to help end the Great Western Schism.

The cardinalate

Cardinals are appointed by the pope, generally from the ranks of his assistants in the curia and bishops of important sees, Latin or Eastern, throughout the world.

In 1059, the right of electing the Pope was assigned exclusively to the principal clergy of Rome and the bishops of the seven "suburbicarian" sees. Because of their resulting importance, the term "cardinal" (from Latin "cardo", meaning "hinge") was applied to them. In the twelfth century the practice of appointing ecclesiastics from outside Rome as cardinals began. Each cardinal is still assigned a church in Rome as his "titular church" or is linked with one of the suburbicarian dioceses. Of these sees, the Dean of the College of Cardinals holds that of Ostia while keeping his preceding link with one of the other six sees. Traditionally, there have thus been only six cardinals who hold the rank of Cardinal Bishop, but when Eastern rite patriarchs are made cardinals, they too hold the rank of Cardinal Bishop, without being assigned a suburbicarian see, still less a church in Rome. The other cardinals have the rank either of Cardinal Priest or Cardinal Deacon.

Only a limited number (which has been set at a maximum of 120) can be admitted to a conclave. The rule has therefore been made that cardinals who have celebrated their eightieth birthday before the pope’s death may not join the conclave. Accordingly, no more than 120 ecclesiastics below the age of eighty may normally be made cardinals, but there may be any number over that age. This has enabled the Pope to confer the cardinalatial dignity on particularly worthy older clergy, such as theologians, or priests who have suffered long imprisonment under dictatorial regimes.

The colour associated with the robes of cardinals is a crimson red, while the red of bishops who are not cardinals (and of Apostolic Protonotaries and Honorary Prelates) is really a Roman purple, and that of the lowest class of monsignors (Chaplains of His Holiness) has a violet hue known as amarinthine red.

The hat and tassels of cardinals' armorial bearings are red; those of bishops and lesser prelates are green. The hat has the same form for all these prelates and should therefore not be identified with the galero, a large hat that once distinguished cardinals.

The episcopate

Bishops are the successors of the apostles in the governance of the Church. The Pope himself is a bishop and traditionally uses the title "Venerable Brother" when writing formally to another bishop. The typical role of a bishop is to provide pastoral governance for a diocese. Bishops who fulfill this function are known as diocesan ordinaries, because they have what canon law calls ordinary (i.e. not delegated) authority for a diocese. Other bishops may be appointed to assist them (auxiliary and coadjutor bishops) or to carry out a function in a broader field of service to the Church. Even when a bishop retires from his active service, he remains a bishop, since the ontological effect of the sacrament of holy orders is permanent.

On the other hand, titles such as archbishop or patriarch imply no ontological alteration, but are generally associated with special authority. Some of the Eastern Catholic Churches are headed by a patriarch. (A few bishops in the Latin Church, such as those of Venice and Lisbon, also have the title of patriarch, but in their case the title is merely honorary.) Three Eastern Churches are headed by a major archbishop, a bishop who has practically all the powers of a patriarch, but without the title. Smaller Eastern Churches (consisting however of at least two dioceses or, to use the Eastern term, two eparchies) are headed by a metropolitan. Within the Latin Church too, dioceses are normally grouped together as ecclesiastical provinces, in which the bishop of a particular see has the title of metropolitan archbishop, with some very limited authority for the other dioceses, which are known as suffragan sees. However, almost all the authority of a metropolitan archbishop to intervene in case of necessity with regard to a suffragan see belongs, in the case of the metropolitan see itself, to the senior suffragan bishop. (In some Eastern Churches, the term "metropolitan bishop" corresponds instead to "diocesan ordinary" in the Latin Church; and an Anglican usage of "suffragan" corresponds to Catholic "auxiliary bishop.") The Latin-Church title of primate is now merely honorary.

Bishops of a country or region form an episcopal conference and meet periodically to discuss common problems. Decisions in certain fields, notably liturgy, fall within the exclusive competence of these conferences. But the decisions are binding on the individual bishops only if agreed to by at least two-thirds of the membership and confirmed by the Holy See.

Priests and deacons

Bishops are assisted by priests and deacons. Parishes, whether territorial or person-based, within a diocese are normally in the charge of a priest, known as the parish priest or the pastor.

In the Latin Church only celibate men, as a rule, are ordained as priests, while the Eastern Churches also ordain married men. Both sides maintain the tradition of holding it impossible for a priest to marry. Even a married priest whose wife dies may not then marry.

To explain this tradition, one theory[14] holds that, in early practice, married men who became priests – they were often older men, "elders" – were expected to refrain permanently from sexual relations with their wives, perhaps because they, as priests representing Christ, were treated as the Church's spouse. When at a later stage it was clear that not all did refrain, the Western reaction was to ordain only celibates, while the Eastern Churches relaxed the rule, so that Eastern Orthodox Churches now require their married clergy to abstain from sexual relations only for a limited period before celebrating the Eucharist. The Church in Persia, which in the fifth century became separated from the Church described as Orthodox or Catholic, decided at the end of that century to abolish the rule of continence and allow priests to marry, but recognized that it was abrogating an ancient tradition. The Coptic and Ethiopic Churches, whose separation came slightly later, allow deacons (who are ordained when they are boys) to marry, but not priests. The theory in question, if true, helps explain why all the ancient Christian Churches of both East and West, with the one exception mentioned, exclude marriage after priestly ordination, and why all reserve the episcopate (seen as a fuller form of priesthood than the presbyterate) for the celibate.

Since the Second Vatican Council, the Latin Church admits married men of mature age to ordination as deacons, but not if they intend to advance to priestly ordination. Ordination even to the diaconate is an impediment to a later marriage, though special dispensation can be received for remarriage under extenuating circumstances.

The Catholic Church and the other ancient Christian Churches see priestly ordination as a sacrament effecting an ontological change, not as the deputizing of someone to perform a function or as the admission of someone to a profession such as that of medicine or law. They also consider that priestly ordination can be conferred only on males. In the face of continued questioning, Pope John Paul II felt obliged to confirm the existing teaching that the Church is not empowered to change this practice: "In order that all doubt may be removed regarding a matter of great importance, a matter which pertains to the Church's divine constitution itself, in virtue of my ministry of confirming the brethren (cf. Luke 22:32) I declare that the Church has no authority whatsoever to confer priestly ordination on women and that this judgment is to be definitively held by all the Church's faithful." (John Paul II, Ordinatio Sacerdotis [15] ) The Catholic Church thus holds this teaching as irrevocable and as having the character of infallibility, not in virtue of the apostolic letter Ordinatio Sacerdotalis itself, from which this quotation is taken and which states this only implicitly, but because the teaching "has been preserved by the constant and universal Tradition of the Church and firmly taught by the Magisterium."

For the Latin Rite, the term "minor orders" was, together with the subdiaconate, abolished in 1969 by Pope Paul VI. Of the four Latin-Rite minor orders, which were stages in the passage to ordination to the diaconate and priesthood, he preserved those of lector and acolyte, applying to them the term "instituted ministries". Some groups particularly attached to the earlier form of the Roman liturgical rite (the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter and the Priestly Union of St. Jean-Marie Vianney), have been permitted to continue to administer the rites of admission to all the previous orders, as well as that of tonsure, which formerly marked entrance to the ranks of the clergy. The Eastern Churches have maintained their less numerous minor orders.

The honorary title of Monsignor may be conferred by the Pope upon a diocesan priest (not a member of a religious institute) at the request of the priest's bishop. The title goes with any of the following three awards:

- Chaplain of His Holiness (called Papal Chamberlain until a 1969 reform [16]), the lowest level, distinguished by purple buttons and trim on the black cassock, with a purple sash.

- Honorary Prelate (until 1969 called Domestic Prelate), the middle level, distinguished by red buttons and trim on the black cassock, with a purple sash, and by choir dress that includes a purple cassock.

- Protonotary Apostolic, the highest level, with the same dress as that of an Honorary Prelate, except that the non-obligatory purple silk cape known as a ferraiuolo may be worn also.

The consecrated life

Consecrated Life, referred to also as Religious Life, is a way of Christian living within the Roman Catholic Church that, publicly professed, is recognized by Church Law (canons 573-746 of the Code of Canon Law). Those who profess it are not part of the hierarchy. They commit themselves, for love of God, to observe as binding obligations what the Christian Gospel proposes as counsels (Evangelical Counsels) rather than commands.

Most join what are called Religious Institutes (cf. canons 573-602, 605-709), in which they follow a common rule under the leadership of a superior. They usually live in community, although some may for a shorter or longer time live the Religious Life as Hermits without ceasing to be a member of the Religious Institute.

Canons 603 and 604 give official recognition also to hermits and consecrated virgins who are not members of religious institutes.

Common usage about the different forms of religious life is notoriously more imprecise in English than in the languages of countries of Catholic rather than Protestant culture (see Catholic order). The term "monks" is commonly applied to members not only of institutes classified as "orders" (grouped in four subsets: canons regular, monks, mendicant friars, and clerics regular), but also of the institutes classified as either clerical or lay religious congregations, and even of societies of apostolic life. And since the houses of monks are indeed rightly called monasteries (abbeys if headed by an abbot), any house of any of these categories is commonly called a monastery. Similarly, all female religious are commonly called nuns; but in their case the general term for their houses is "convent", rather than the term proper to the houses of nuns in the strict sense.

Members of Religious Institutes for men are usually addressed as "Brother", unless they are priests, in which case the form of address is "Father". In Institutes for women most members are addressed as "Sister", and the superior generally as "Mother", "Mother Superior" or "Reverend Mother". The formal title for the superior of a community or a whole institute varies according to the category of the institute: even in English few would address a Jesuit superior as "Abbot" or an abbot as "Guardian" (the term used by Franciscans).

There is a great variety of Religious Institutes, both male and female. Some have only lay members, while among male Institutes some have both priests and lay members, and yet others only priests and men preparing for priesthood. Some date from the earliest centuries of Christianity, others spring up every year. Their apostolates, too, vary considerably, depending on the vision of the founder: some have an apostolate specifically of prayer, often called "contemplative", others have an outgoing apostolate, e.g. teaching, missionary work. The rare "double communities" known in earlier centuries, where monks and nuns prayed and worked alongside each other under the leadership of only one superior, usually an Abbess, have not survived.

The oldest existing forms of Religious Institutes are those of monks and nuns, such as the Basilians of the East and the Benedictines of the West, who live in monasteries. Around the thirteenth century Mendicant Orders arose, such as of those of the Dominicans and Franciscans. Unlike the monks and nuns of the earlier Orders, the members of the latter Orders had their houses (which they called convents, not monasteries) not in the country but in the towns, which were becoming increasingly important. One of the best known of those that appeared still later is the Society of Jesus, which today is the Religious Institute with the largest number of members (known as Jesuits).

According to canon law (cf. canon 579), religious communities normally begin as an association formed, with the consent of the Diocesan Bishop, for the purpose of becoming a Religious Institute. After time has provided proof of the rectitude, seriousness and durability of the new association, the Bishop, having consulted the Holy See, may formally set it up as a Religious Institute under his own jurisdiction. Later, when it has grown in numbers, perhaps extending also into other dioceses, and further proved its worth, then the Holy See may grant it formal approval, bringing it under the Holy See's responsibility, rather than that of the Bishops of the dioceses where it is present. For the good of such Institutes and to provide for the needs of their apostolate, the Holy See may exempt them from the governance of the local Bishops, bringing them entirely under the authority of the Holy See itself or of someone else.

Typically, members of Religious Institutes take vows of evangelical poverty, chastity and obedience (the "Evangelical Counsels") to lead a life in imitation of Christ Jesus. For some the vow of stability in a monastery or to live according to a particular written rule is considered to include these vows. Other Institutes add further vows.

Secular Institutes (cf. canons 710-730) are another form of Consecrated Life. They differ from Religious Institutes in that their members live their lives in the ordinary conditions of the world, either alone, in their families or in fraternal groups. They include, among others, Caritas Christi, The Grail, and the Servite Secular Institute.

Comparable to Religious Institutes are the Societies of Apostolic Life (cf. canons 731-746), dedicated to pursuit of an apostolic purpose, such as educational or missionary work. They do not take religious vows, but live in common, striving for perfection through observing the "constitutions" of the society to which they belong. Among them are, for example, St. Philip Neri's Institute of the Oratory, the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul, and the Priests of St. Sulpice.

As mentioned earlier, individuals unattached to any such institutes can be granted official recognition as hermits or consecrated virgins. Although widows appear to have been given special attention in the early Church, present canonical legislation does not mention them as a category calling for similar recognition.

Worldwide distribution

- For the Roman Catholic Church regionally and by country see Category:Roman Catholic Church by Country and Category:Roman Catholic Church by region

The total number of Catholics in the world is over one billion. They are found in nearly every country, though they are more concentrated in the Americas and Europe. They currently make up 63% of the population of North and South America, 40% of Europe, roughly 20% of Sub-Saharan Africa, and 3% of Asia [17].

In Europe, Catholic majorities are found in Andorra, Austria, Belgium, Croatia, France, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Malta, Monaco, Poland, Portugal, San Marino, Slovakia, Slovenia and Spain. Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland, as well as Northern Ireland, are about equally divided between Catholics and Protestants. In the Czech Republic, Roman Catholics make up 39% of the population. Catholics are a significant minority in Britain, where their faith underwent a revival in the 19th and early 20th Century after three centuries of persecution and official repression.

Nearly all Latin American countries have large Catholic majorities, among them such heavyweights as Argentina, Brazil, Mexico and Peru. Catholics in the United States of America are more numerous than any other single Church: as a result of massive immigration, mainly from countries like Ireland, Italy, Germany (and, later, from Latin America), their number grew from virtually nothing in 1790 to about a quarter of the total population by 1920, a proportion that remains today. Catholics are a large minority in neighbouring Canada, where there has been a strong historical presence of France and much immigration from Catholic countries.

In Asia, the Philippines (once a Spanish colony) and East Timor (a former Portuguese colony) have Catholic majorities, and most Christians in Lebanon are Catholics, while a significant Catholic population has developed in South Korea, India, and Vietnam. In China, however, the Catholic Church is repressed by the State, which have his own puppet religion.

Australia, like the United States, has a large Catholic population representing the largest single Christian denomination.

There are approximately 115 million Catholics in Africa.

The number of Catholics in the world continues to increase. The increase between 1978 and 2000 was 288 million. Protestant evangelicals have succeeded in making inroads into parts of Latin America, but remain a small percentage of the population. In most industrialized countries, church attendance has decreased since the 19th century, though it remains higher than that of other "mainline" Churches.

Criticisms and controversies

Over the centuries, the Catholic Church has encountered criticisms for numerous reasons. (Some particular controversies are discussed in separate articles. See, for instance, on the charge of anti-Semitism, Relations between Catholicism and Judaism.)

Pope John Paul II acknowledged publicly that the Catholic Church (and its members) has sometimes been involved in questionable activities, and asked God to forgive the sins of its members, both in action and omission.

Historical criticism

Historically, the Church's response to heresy through the Inquisition and its alleged association with witchhunts have brought criticism. Pope John Paul II apologized for certain historic excesses in May 1995.

Enlightenment philosophers perceived the Church's doctrines as superstitious and hindering the progress of civilization. Many thinkers and academics criticized it for opposing scientific advancement, the trial of Galileo Galilei being a famous, though still hotly-debated, example. Pope John Paul II publicly apologized for the Church's actions in the trial on October 31, 1992.

Contemporary criticism

In recent times, the Catholic Church has sustained criticism from many quarters on the basis of several of its teachings.

Its exclusion of women from the ranks of the ordained clergy and so from many of the most important decisions is seen by some as unjust discrimination (at a time when feminism and other social and political movements advocating equal access have removed barriers to the entry of women into professions that were traditionally male strongholds). However, many other Christian denominations and movements, as well as many non-Christian religions, also hold that only males can be members of the priesthood. The Church believes that Jesus chose men to form the college of the twelve apostles, and the apostles did the same when they chose collaborators to succeed them in their ministry. The Church recognizes herself to be bound by this choice made by the Lord himself. The matter has been determined to be closed for discussion by Rome.

The Catholic Church also has a strict rule of mandatory celibacy for priests in the Latin Rite. Many criticize this tradition, seeing it as unrealistic. It is in strong contrast to Christian traditions issuing from the Protestant Reformation, essentially none of whom maintain the practice. It also differs from that of the Churches of the East, which require celibacy for bishops, but exclude for priests only the possibility of marriage after ordination. Some claim that mandatory priestly celibacy only appeared in the European Middle Ages. The decrease in candidates for the priesthood in Western countries, though not worldwide, in recent years has been called a vocations crisis for those countries. Some believe that relaxing the celibacy requirement might solve the shortage, while others think the shortage is due instead to greater secularization and a general lack of faith among believers. In October 2005, at a world-wide synod of Catholic Bishops held in Rome to discuss the Eucharist, the priesthood shortage was brought up, along with the idea of ordaining viri probati - married men of tested virtue. Overall, the synod did not recommend any change in the status quo and stated that this was not a good path to follow. It has been suggested that a common ground on this issue could not be met and that it would be up to individual bishops or bishops' conferences to raise the issue again if they believe their specific situations warrant it. Pope Benedict XVI is expected to address this issue in his post-synodal apostolic exhortation in 2006.

Some have argued that reform in these two areas could make a career in the priesthood more appealing among the faithful and would update the Church's image as more relevant to modern society. Many of them do not recognize the clôture of debate within the Church on the first of these issues. However, they also recognize that such dramatic changes in Church traditions would alienate conservative Catholics worldwide, and, in the case of the proposed ordination of women, would be seen as nothing less than a revolution. It has also been pointed out that, in spite of admitting ordination of women and of married men, mainline Protestant Churches too are experiencing difficulty in drawing people in the same countries to ministry. And it has been remarked that seminaries and dioceses that are more insistent on Catholic values are in practice much more successful in attracting vocations to the priesthood than those that take a more permissive attitude.

Some criticize the Church's teaching on sexual and reproductive matters[18]. The Church requires members to eschew homosexual practices (CCC 2357), artificial contraception (CCC 2370), and pre-marital sex (CCC 2353). The procurement of abortion carries the penalty of excommunication(CCC 2272), as a specific offense. Some see the Church's stance as restricting women's "reproductive rights". However, these doctrines are shared by many conservative members of the Christian tradition outside the Catholic Church.

Some heavily criticize the Church's teaching on sexual abstinence and its opposition to promoting the use of condoms as a strategy to prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS (or teen pregnancy or STD) as counterproductive. They comment that, even if abstinence is a worthy ideal, it is not realistic to expect a high proportion of people to follow the practice, and so contraceptives and safe sex practices should be promoted. The Church argues that there is considerable proof that distributing condoms and failing to condemn promiscuity amounts to condoning the behaviors and actually increases HIV infection.

The Church is criticized for its opposition to scientific research in fields such as embryonic stem cell research, which the Church teaches would cause the utilitarian destruction of a human being, or simply put, an act of murder. The Church argues that advances in medicine can come without the destruction of human embryos; for example, in the use of adult or umbilical stem cells in place of embryonic stem cells.

Political advocacy by bishops and other officials have also aroused controversy. For example, some bishops in the United States denied the Eucharist to politicians and parishioners who hold views contrary to the Church on important moral questions. In predominantly Catholic Philippines, some bishops and priests have also been criticized for political advocacy.

Much of the recent criticism of the Church, particularly in the United States, has centered around the sex abuse scandal. The failure of some bishops to take action against offending priests is reported to have undermined the Church's moral authority among some segments of the public.

Traditionalist Catholics see the Church's recent efforts at reformed teaching and practice (known as "aggiornamento"), in particular the Second Vatican Council, as not benefitting the advancement of the Church. Some groups claim the Church has betrayed the core values of Catholicism, and reject some of the decisions of the Holy See that they see harmful to the faith.

Others go so far as to characterize the current leaders of the Roman Catholic Church as heretics. Several groups, known as sedevacantists, claim that the current Pope (as well, perhaps, as some of his immediate predecessors) is not legitimate. A handful of them have appointed papal replacements: see list of sedevacantist antipopes.

See also

- Other articles on the Catholic Church

- History of the Roman Catholic Church

- Christianity

- Christian apologetics

- Roman Catholic Church by country

- Catholic Worker Movement

- Primacy of the Roman Pontiff

- Traditionalist Catholic

External links

- Vatican: the Holy See

- Catechism of the Catholic Church

- The Catholic Encyclopedia Resource concerning Catholic history and doctrine as well as related matters of philosophy.

- Mass Times A directory of Mass times, parish locations, directions and phone numbers for traveling Catholics

- Catholic Hierarchy information on Catholic bishops and dioceses

- The Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church information on the Cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church

- Apologia: Apologetics and Traditional Catholic Instruction

- EWTN American Catholic television station, live streaming in English and Spanish.

- myCatholic.com A customizable Catholic web portal.

- Statistics on the Global Catholic population

- Catholic Culture Excellent Catholic search engine

- Catholic Answers One of the largest lay-run apostolates of Catholic apologetics and evangelization

- American Catholic Catholic Church Questions - FAQs about Catholicism